Empire Strikes Back Was The Reason George Lucas Left The Director's Guild

With the release of "Star Wars" in 1977, it quickly became clear that filmmaker George Lucas was changing the way Hollywood worked on numerous levels, from the types of films being developed to the proliferation of new special effects techniques to the way movies were marketed and merchandised to what series meant for kids could do.

Yet Lucas' influence didn't stop with merely one film — he continued to innovate and push the envelope throughout his career, from shepherding the creation of the THX sound system to helping develop what would become Pixar to pioneering the usage of non-linear editing, all of which are staples of the film industry in 2023.

The changes to filmmaking that Lucas helped usher in aren't all as seismic as those examples, however. Around the release of "The Empire Strikes Back" in 1980, Lucas publicly left the Director's Guild of America over a dispute regarding the film's on-screen credit structure and usage. The dispute set a precedent of style that is still seen in countless films to this day, especially within big-budget blockbusters.

'Star Wars' changes the credits format

The 1960s and '70s began to demonstrate a sea change overall in the presentation of films. For decades, movies were released with a sizable set of opening title credits that listed only the main department heads and principal cast members, and closed with a simple title card that said some variation of "The End." That began to shift during the '60s, when films like "West Side Story" threw all their credits at the end of the film instead of the beginning, and movies began to include a mixture of both main and end titles.

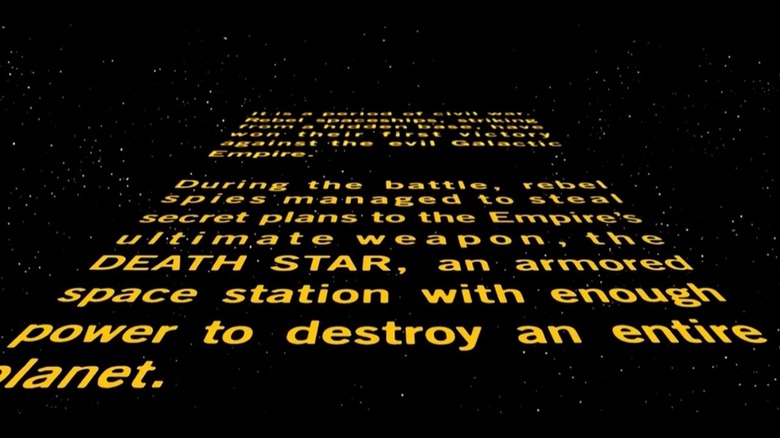

While this shift was gradual, the expected norm circa 1977 was that there was a main title sequence and a brief end credit roll. Lucas eschewed that expectation with "Star Wars," as the film began simply with the 20th Century Fox logo, a title card for Lucasfilm, and then the "Star Wars" logo and its infamous opening crawl detailing the backstory of the film. All the end titles, then, including Lucas' director's credit, appear at the close of the movie.

The Director's Guild had no dispute with this structure at first, assumedly because there were no given credits at the top of the film; a DGA rule states that if any individual receives a credit at the beginning of the movie, the director's credit must be included at the same time.

The DGA strikes back

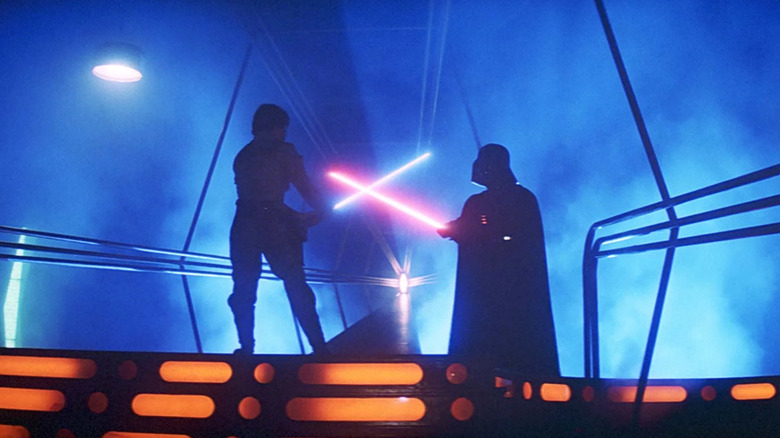

That all changed, however, when "The Empire Strikes Back" was being prepared for release in 1980. As with "Star Wars" before it, Lucas intended the film to open in the exact same way "Star Wars" had, but soon discovered that the DGA's lack of beef with the prior movie's credit structure was more pedantic than he'd realized. The DGA had allowed "Star Wars" to remain unchanged because Lucas was the director, and thus his "A Lucasfilm Limited Production" opening credit was viewed technically as a credit for himself. Now that Lucas had hired Irvin Kershner to be the director of "Empire," the DGA balked.

According to a 1981 profile of Lucas in The New York Times by Aljean Harmetz, Kershner "did not object" to Lucas using the same credit structure he'd used before, but that didn't appease the DGA. As a result, Lucas decided to resign from the Guild, and kept the credit order for "Empire" the way he always wanted it. This resignation is a prime example of Lucas' contempt for the politics of Hollywood — as that same profile explained, Lucas "can be arrogant about his values and priorities," with an anonymous colleague of his being quoted as saying, "The vision inside his head is crystal clear. That he can not be turned from it or corrupted by outside influences is the key to his success."

The DGA issue leads to the fate of 'Return of the Jedi'

Famously, Lucas went on a fairly wide and varied search for a director for "Return of the Jedi," the follow-up to "Empire Strikes Back." While a lot of these potential choices were made for aesthetic and artistic reasons, Lucas was also looking for someone who was either just beginning their career or otherwise wasn't a member of the DGA thanks to his leaving the Guild. In this light, it becomes clearer why Lucas would entertain the notion of hiring young, maverick directors like David Lynch and David Cronenberg for the third "Star Wars" film.

As it happened, Lucas found his best candidate by skipping American directors entirely. Admiring 1981's "Eye of the Needle," Lucas pursued that film's director, the Wales-born Richard Marquand. Many "Star Wars" conspiracy theorists considered Marquand a proxy director for Lucas based on Marquand's relatively minor filmography at the time of his hiring, yet it seems clear that Lucas' choice had more to do with his DGA dispute than looking for someone he could boss around. In fact, as this interview with Marquand from 1984 proves, he indeed gave "Jedi" his own spin, something he otherwise may not have been able to do had Lucas been given access to a wide variety of more local filmmakers.

The rise of main-on-end titles

In the immediate years after the release of the original "Star Wars" trilogy, the most common form of film credit structure featured the mixture of main titles followed by a lengthier end credit roll at the close of a movie. Yet the influence of "Star Wars" popularizing no opening credits beyond a title card began to be felt more frequently, especially toward the end of the '80s as sequels like "Lethal Weapon 2" and "Die Hard 2" adopted the format.

Other maverick filmmakers that came along during the 1990s continued to mess with credit structure: Quentin Tarantino began organizing his film credits by presenting a main title that would leave off his "Written and Directed By" credit, placing it at the end of the movie as if the film itself had interrupted and delayed the credit sequence, while Paul Thomas Anderson began shifting all of his credits to the end of the film, including the title card. Soon enough, a number of other films and filmmakers adopted this format, giving audiences the sensation of plunging directly into a movie without the "introduction" of a credit sequence.

When the Marvel Cinematic Universe began in 2008, "Iron Man" began with a cold open scene followed by a title card and then waited for the rest of its credits by the end. By 2011, Marvel utilized this main-on-end title structure almost completely, and the films with opening title sequences (like "Guardians of the Galaxy") became outliers rather than the norm.

These days, audiences are used to a variety of disparate credit structures, with the MCU helping to dissuade people from getting up and leaving en masse during end credit rolls thanks to the increasing popularity of post-credit scenes. It's funny to realize that, in a weird way, we have George Lucas to thank for all this.