One Heavy Metal Scene Was So Gruesome, Artists Refused To Work On It

Launched in 1977, the counterculture art magazine Heavy Metal took the underworld by storm. Not just about music, Heavy Metal was a venue for bizarre, ultra-violent, unabashedly sexual comic stories for college kids with a healthy interest in wild artistic extremes. In 1981, producers Ivan Reitman and Leonard Mogel elected to adapt Heavy Metal into a feature film, presenting audiences with a series of bizarre, animated, nudity-heavy, blood-soaked fantasy vignettes for the grindhouse crowd.

The bookend material for the "Heavy Metal" feature film was a young girl's discovery of a mysterious intelligent orb calling itself the Loc-Nar (Percy Rodriguez). The Loc-Nar explains that it is a solid ball of concentrated evil, and has caused wars and galaxy-wide corruption throughout its history. Each of the shorts in "Heavy Metal," were worked on by a different team of animators, and told another chapter in the history of the orb, although sometimes tangentially. The soundtrack is one of the best in cinema history, including Black Sabbath, Cheap Trick, Devo, Journey, Sammy Hagar (who sang the rockin' title tune), and Blue Öyster Cult.

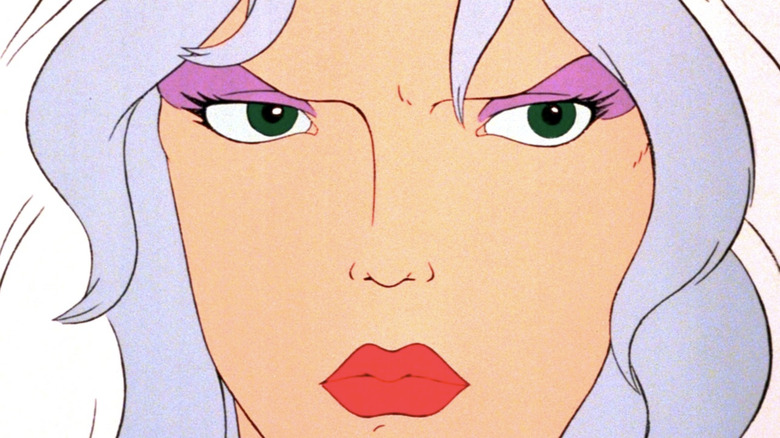

In between the prologue and the epilogue, "Heavy Metal" was made of seven distinct sequences, some of them better than others. The seventh short was called "Taarna," and it was about the Loc-Nar spewing volcanic slime onto the populace of a distant planet, turning them into violent, mutant marauders. The local scholars needed to be protected by a heroic, bikini-clad warrioress who rides a pterodactyl. The mutants murder many. Taarna murders them back.

In the August 1981 issue of Heavy Metal, the magazine published a long and thorough article by Brad Belfour detailing the making of the feature film. In the article, filmmakers recalled one particular death in "Taarna" that had animators balking.

The dying boy

The "Taarna" segment was inspired by a series seen in the French comic book Métal Hurlant. The segment, called "Arzach," was authored by Jean 'Moebius' Giraud and followed a pterodactyl-riding mute warrior, although he was not a half-naked woman in the original version.

"Heavy Metal" was produced in Canada, and Gerald Potterton, who oversaw all the separate sequences, also directed the "Taarna" segment himself. One of Potterton's animators, a French-born artist named Jose Abel, was in charge of animating a notable supporting character in "Taarna." When the evil, corrupted mutants storm a palace, they fire arrows and guns into the bodies of the unarmed civilians inside. A young man, afraid, hides behind a column. When a mutant discovers him, he runs toward the camera in a panic. The boy is shot multiple times from behind, the bullet holes exploding toward the camera. The character falls, his dead face passing slowly in front of the audience. It's all very gruesome.

According to the making-of article, Abel animated the dying man ... perhaps to too realistic a degree. Keep in mind how many drawings it takes to animate a single second of film — typically 12 — and how many cels a colorist would have to paint in order to complete it. Knowing that it would take dozens of hours just for those few seconds, many of the ink-and-paint workers refused to work on it.

The animation process

"Heavy Metal," to this day, remains one of the more notable animated films for adults — outside of Japan — that has ever been produced. In the making-of article, Potterton is described as a very active, animated character in himself, and, like many animators, will often use his own physical performance to inform his animated figures. The animators are the actors, and Potterton speaks eloquently about the approach animation directors take to performance as opposed to live-action directors. He said:

"You meet live-action people who say, 'I wish I could do animation.' It seems to me a hell of a lot easier to make the transition from animation to live-action because you're trained from the start to visualize in terms of already edited scenes. In animation, you can't afford to shoot a scene several different ways; you must know what you want and do it right the first time!"

This "frozen in time" approach to filmmaking would force animators to stay in small moments for extended periods, maybe even weeks, just getting a few seconds of film finished. This would mean when it came to death scenes, animators have to live inside death, looking at the same dying face over and over again for days. When taking that into mind, it's perfectly understandable why animators wouldn't want to work on it.

The sequence was ultimately finished, of course, and it's just as disturbing as one might assume. It was just one more way "Heavy Metal" pushed the envelope.