The Walking Dead Should Have Ended With Season 5

When you talk to someone about "The Walking Dead," one question inevitably comes up, and no matter the answer it's met with a word or nod of understanding. To an outside observer, it may sound a little bit like we're talking about sobriety. "When did you quit?" "I quit three years ago," or six, or seven. By my calculations, based on the difference between the highest point of the show's ratings and the lowest, there are at least 14 million of us walking around who once watched the apocalyptic drama series live, but stopped tuning in somewhere along the way. Maybe we're the real walking dead, or maybe it's the people who chose to keep trucking through the zombie series that felt like it would never end.

There was a time when the series based on Robert Kirkman's zombie comics seemed like the coolest show in the world. It arrived before "Game of Thrones" made epic TV feel normal, and before "The Avengers" made geek culture feel like a powerful currency. It was a phenomenon in the truest sense of the word, the kind of event television that made you want to tell everyone you know about it. I remember watching the first episode, 2010's "Days Gone By," with a friend and feeling gripped by obsession by the time the end credits came to a close. I remember crying with excitement over the season three trailer in a cafe at Comic-Con, having missed the Hall H panel but still feeling the contact high regardless.

The show was once television at its most thrilling

Those early seasons, before the show started diminishing with an impressively tedious half-life, feel like a series of massive, thrilling moments presented one after another. When pizza delivery boy Glenn Rhee (Steven Yeun) helped disoriented deputy Rick Grimes (Andrew Lincoln) disguise himself in human viscera to make his way out of a zombie horde, that felt like cable TV at its most exciting. When Carl (Chandler Riggs) got shot, when Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies) gave birth, when the CDC said everyone was infected, and when hothead Shane (Jon Bernthal) turned into a walker in front of our eyes, the show felt like a fantastic intersection between horror and art. Most of all, it felt like appointment television.

But somewhere along the way, millions of us checked out. I can't say with authority that "The Walking Dead," which ends this weekend after an eleventh season that was split across fifteen months, is bad. That's because I haven't seen more than an episode per season in years. I do know that lots of talented people worked hard on it, and I'm sure there were bright spots in its later seasons, but I also know it lost me in the same way it lost most of its fans — with one too many punishing character deaths.

The brutality wore viewers down

For me, it wasn't the infamous moment when Glenn got a barbed wire baseball bat to the head that made me click off "The Walking Dead." I was distraught two seasons earlier when the show killed off Beth Greene (Emily Kinney), the farm girl who had grown into a hero after making her wander aimlessly around a sinister hospital for half a season. Beth wasn't most peoples' favorite character, but she was mine, especially after the great fourth season chapter "Still" unfolded like a "Breakfast Club" bottle episode in which she and fan favorite Daryl (Norman Reedus) helped one another process their traumas. Beth wasn't as overtly badass as Rick, Daryl, or Michonne (Danai Gurira), but she was a teenage girl like me, and she was capable in her own way. Plus, she had a secret weapon: hope.

But Beth got kidnapped in the very next episode, and after months of press interviews in which the cast and crew assured us that her heroic arc would continue, she ended up unceremoniously shot during a mediocre midseason finale — one that was frustratingly spoiled on the show's official Facebook page before most people got to see the episode. I stuck with the show for the rest of season 5, but I found Beth's pointless death extremely painful, and I just couldn't muster up any more enthusiasm. I don't expect that most people tapped out of "The Walking Dead" around the same time as me, but I do suspect that most of us did eventually for pretty much the same reason: that, for all its artistry, this show seemed designed to hurt us more than entertain us. If I wanted to think about how everyone I love will die, I could do that without sitting through 177 episodes worth of grueling, brutal reminders, thanks.

It could've ended with 'The Distance'

By now, "The Walking Dead" has clearly outstayed its welcome, but when should it have ended? What concluding point could've maintained the style of Kirkman's comics, the mastery of initial showrunner Frank Darabont's vision, and the talent of the performers who made us love these characters?

While not everything in its early seasons was perfect (see: the overly-long Governor conflict, the hospital plot I just mentioned), there's a natural stopping point built into the show's fifth season that, in a perfect world, may have been its finale. It's not actually the season finale, but "The Distance," the episode that ends with the survivors heading into the long hoped-for safe zone, Alexandria. Of course, Alexandria wouldn't turn out to be an impenetrable fortress, and it wasn't the end of Rick, Michonne, Glenn, and the rest of the group's worries, but their admission into the town represented an optimism that has often been in short supply in this story.

This is, of course, just a thought experiment. If "The Walking Dead" had ended with the group headed through the gates of Alexandria, we wouldn't have gotten the show's apparently pretty great ninth and tenth seasons, the development of Rick and Michonne's relationship, the return of Morgan (Lennie James), or characters like Jesus (Tom Payne) and King Ezekiel (Khary Payton). But what we would have gotten is something that "The Walking Dead," in its exhaustive attempts to examine life and death and danger and peace from every possible angle for as long as it possibly can, rarely gave us: ambiguity.

Ambiguity and hope

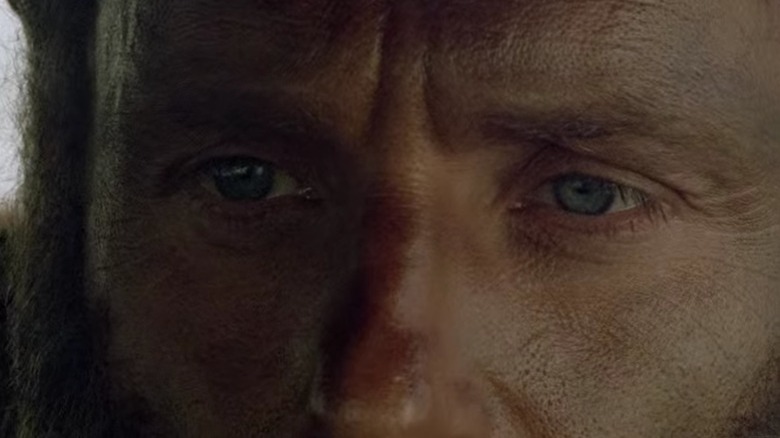

There's a moment in the last scene of "The Distance" that I love. Rick looks about as world-weary as he ever has as the group approaches the gates of Alexandria. He's haggard, twitchy, and seems like he's on the verge of tears. Then, after the ambient noise of nature clears away, he hears kids playing. They're laughing and screaming, and as the camera captures his eyes in a warmly shot close-up, we know it's the first time he's heard a happy scream in a long, long time. For a moment, the tension he's held in the clench of his jaw and the squint of his eyes vanishes. The episode ends as the group steps into Alexandria.

It's an ending that would have asked viewers to take (or refuse) the same kind of leap of faith presented by shows like "The Leftovers" and "The Sopranos," and even the first installment of another beautifully told apocalypse story, the video game "The Last Of Us." We can choose to believe in a future that has laughing kids in it, or we can be beaten down and made cynical by all the horrors we've seen so far, and in the context of the story so far, either conclusion would feel like truth. Either conclusion would also feel more important and more personal to each viewer than a story about zombies had any right to.

When "The Distance" ends, we don't get to see what's on the other side of those gates. It could be a trap, or it could be a fulfilled promise. If it's the latter, it's the kind of promise the characters in "The Walking Dead" have yearned for across its eleven seasons. It's the same promise everyone hopes for, really: that somewhere nearby, people are happy and safe.