14 Movies Like American Psycho That Will Get Your Heart Racing

In the decades since the release of Mary Harron's seminal horror-comedy "American Psycho," the film has been meme-ified to death. There's a page on Know Your Meme that breaks it down, tracking the way internet users have made gifs of Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) flexing in the mirror during sex, cracked jokes about his love of Huey Lewis and the News, and turned his axe-swinging violence into pithy reaction images about having a bad day at work.

Rewatching "American Psycho," it's easy to see why the film has resonated for so long: it's very good! Harron turned Bret Easton Ellis' horror novel into a biting satire of '80s yuppie culture, featuring a cracking performance from Bale that is downright zany at times. Crucially, its horror sequences are also very effective; Harron finds real tension in moments like the one involving Chloë Sevigny and a nail gun. The movie also has a lot on its mind. In addition to simply being entertaining — which is not to discount just how entertaining the film is — "American Psycho" is a provocative watch and a chilling character study that leaves audiences with lots to chew on long after the credits have rolled.

In other words, "American Psycho" does a lot of things, and it does them all well. There aren't many movies exactly like it, but if you're looking for something to follow-up the film with, here are 14 movies like "American Psycho" that will get your heart racing.

Nightcrawler (2014)

"American Psycho" is a film that puts us squarely in Patrick Bateman's mind. We see the world through his eyes and hear his internal narration, to the point where by the end of the film, we are just as unable as he is to tell reality from delusion. That kind of psychological closeness to a character who is losing their grip on sanity can be thrilling. Another film that gets at a similar idea is "Nightcrawler," Dan Gilroy's film starring Jake Gyllenhaal as an ambitious videographer who is willing to do anything to get ahead.

Louis Bloom (Gyllenhaal) is what they call a "stringer," an independent cameraman who takes his own footage of emergencies to sell to news stations. Over the course of "Nightcrawler," we witness Bloom's descent into craven opportunism. He throws all morality out the window in pursuit of the best-possible, most-shocking footage he can capture, and if that means getting too involved in the crime scenes he visits, well ... anything for a paycheck. Like Patrick Bateman, he spends the movie shedding any layers of guilt or ethics he might have once retained, ending the film as a hollow man.

Another similarity is that both "American Psycho" and "Nightcrawler" are very much interested in their stars' bodies. Bale packed on muscle for his role as the yuppie serial killer, while Gyllenhaal slimmed down significantly to play Bloom. Both films understand how unsettling it can be to see a star you know well, whose appearance just seems ... off.

The Body (2018)

After Patrick Bateman kills Paul Allen (Jared Leto), he stuffs his body into a duffel bag and drags him through the apartment lobby into a waiting taxi cab. It's basically a sight gag; the bag trails blood, and we can't help but wonder why no one realizes he's obviously just killed someone. "The Body" is a Hulu Original film released as part of its "Into the Dark" film series with Blumhouse, and it's essentially that sight gag stretched out to feature length.

Tom Bateman (no relation to Patrick) plays Wilkes, a hitman who kills someone on Halloween night and then has to transport the plastic-wrapped body through crowded streets of people who think it's part of a costume. (The reference is intentional. Someone even asks him, "What are you, like a British-American Psycho?") It's more overtly comedic than "American Psycho," but there are still a number of very fun, tense sequences that make "The Body" work as the rare film where the horror and comedy elements both pull their weight.

At its core, "The Body" is a slasher film told from the point of view of the killer, and the same could even be said about "American Psycho." "People wear masks their whole lives, pretending that life has meaning," Wilkes cautions a woman who gets too close. "When you kill somebody, all of that's gone." It may as well be a line from "American Psycho," whose lead character frets that his "mask of sanity is about to slip."

Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile (2019)

One of the most complex aspects of "American Psycho" is the fact that Christian Bale is so handsome and charming in it. The film is as much in love with Patrick Bateman's body as he himself is, and if we weren't able to see why Bateman is able to fool others (and if we weren't able to allow ourselves to be ever-so-slightly fooled by him, too) then the film wouldn't work nearly as well as it does.

Joe Berlinger's "Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile" functions similarly. Zac Efron plays Ted Bundy, and through this casting — thanks to Efron's years of roles that trade on his All-American charm — we are able to get a glimpse into why so many people found Bundy so charismatic. Looking at photos of the actual Bundy, it's hard to understand what made him attractive to the legions of women who wrote him letters in jail and showed up at his trial hoping to woo him. Put Zac Efron in the role, however, and it starts to make a bit of sense.

That's an extremely uncomfortable topic for a film to lean into, particularly given the tenor of recent conversations around true crime and the "glamorization" of serial killers. In "Extremely Wicked..." though, it's a productive discomfort. Berlinger is primarily a true-crime documentarian, having also directed Netflix's "Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes," and he seems to understand full well the ethical dilemmas brought about by his film.

God Bless America (2011)

"American Psycho" is a satirical film that takes aim at the self-obsessed, materialistic culture of 1980s Wall Street. Patrick Bateman is disgusted by the people around him, and he's so fixated on markers of wealth that he kills people around him who remind him of his own inadequacy.

Bobcat Goldthwaite's "God Bless America" takes a similar stance toward the early social media years of the Obama era. Joel Murray plays Frank, a man who reaches a breaking point when he learns that he has a malignant brain tumor. He's deeply disgusted by the rapidly-growing culture of vapid reality television and the search for online fame. When he teams up with a young girl (Tara Lynne Barr) who says she feels the same way he does, they embark on a killing spree together.

"God Bless America" trades the skyscrapers of New York City in "American Psycho" for a road trip across the heartland, but both films aim to say something about the country as a whole. As the leads of both "God Bless America" and "American Psycho" seek out and slaughter people who represent society's ills, both films balance black comedy with a deep sense of unease and isolation.

The House That Jack Built (2018)

One interesting aspect of "American Psycho" is what the film leaves out. We see a few of Patrick Bateman's murders, but by the final act — as victims discover other bodies in closets and as Bateman makes a tearful, confessional phone call to his lawyer — we realize that he's been far busier than we knew.

Lars von Trier's "The House That Jack Built" is constructed around this very idea. "I will tentatively divide my tale into five randomly-chosen incidents over a 12-year period," Jack (Matt Dillon) says at the beginning of the film. He relates five points in his life that he claims are not representative of any particular arc, but as we witness Jack become more adept at killing (more sadistic, more brutal), we realize that we are witnessing the escalation of true evil.

Jack shares a lot of similarities with Patrick Bateman, making "The House That Jack Built" sort of an art-house mirror version of "American Psycho." In addition to being obsessed with cleanliness, both killers are frighteningly self-aware of what they lack. "I went to great lengths to fake normal empathy, in order to hide amongst the masses," Jack recalls as he practices facial expressions in the mirror. Like Bateman, Jack is fascinated with the way he seems to escape any consequence for his actions; we begin to question whether he's telling the truth. This is a difficult, brutal film, but it's a worthwhile one for how it complements themes in "American Psycho."

Fight Club (1999)

Patrick Bateman is a man obsessed with his appearance, perfecting the mask he wears in order to slip through society undetected. He guides the viewer through his extensive skin-care routine, his daily ab exercises, and his love of Valentino suits, all in hopes of crafting himself into a perfect physical specimen on the outside because he feels nothing on the inside. The main characters in "Fight Club" would hate him.

"I felt sorry for guys packed into gyms, trying to look like how Calvin Klein or Tommy Hilfiger said they should," the Narrator (Edward Norton) says, looking at too-perfect bodies on subway ads. His charismatic counterpart, Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), has a pithy answer to that: "Self-improvement is masturbation."

David Fincher's biting satire of masculinity in crisis is based on a Chuck Palahniuk book of the same name. It's about a man who is existentially tired of consumerism, and when he meets a magnetic guy who convinces him to join a fight club — getting out his aggression at the world by beating up other men — his life spirals into nihilism and violence. "American Psycho" and "Fight Club" were released a few years apart at the end of the '90s, and both are speaking to the same crisis of masculinity. Both films are easily misinterpreted as reveling in the physical excess they depict when both are actually critiquing it. Both thrilling and pulse-pounding while both smarter than they initially appear, they make a perfect pair.

A Cure for Wellness (2016)

"American Psycho" is a movie as much concerned with aesthetics as its central character is. It's a movie about how people are shaped (read: warped) by the spaces they inhabit, about how cookie-cutter skyscraper office buildings and stark-white minimalist apartments reflect the hollow interiors of the people who exist there. It's a movie about how creepy it is when someone is murderously obsessed with which apartment has the better view, but it's also a film that knows how frightening an apartment looks when it's covered in plastic sheeting and newspaper ... the better to catch blood droplets with.

Another horror film fascinated by architectural aesthetics is "A Cure for Wellness," Gore Verbinski's 2016 film. The movie is about Lockhart (Dane DeHaan), a twentysomething businessman who has molded himself to fit what his company requires of him. Unlike "American Psycho," "A Cure For Wellness" is a fish-out-of-water tale about what happens when that sort of corporate-ladder-climbing ambitious character moves from endless rows of cubicles to a picturesque, Gothic wellness retreat in the mountains.

Verbinski's cinematography continuously emphasizes both pristine and broken symmetries, contrasting its characters against their environments. Even as the world around Lockhart seems to go insane — as he discovers a bloody world filled with writhing eels, youth-obsessed wellness cults, and more — he sticks it out, believing his loyalty to his company trumps all other concerns. Might he actually need the "cure" promised by the creepy inhabitants of the retreat after all?

We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011)

In "American Psycho," Patrick Bateman suspects that something essential about himself is missing. "I have all the characteristics of a human being: blood, flesh, skin, hair," he narrates, "but not a single, clear, identifiable emotion, except for greed, and disgust." Above all else, he is lacking the ability to feel empathy, to understand his fellow human beings as human.

In "We Need to Talk About Kevin," a mother (Tilda Swinton) suspects that her son Kevin (Ezra Miller) is growing into a sociopath. Ever since he was an infant, she feels as though he gets a sadistic pleasure out of seeing her upset; he cried constantly as a baby, for example, and she fears that when she looks into his eyes, there's a nothingness looking back at her.

"American Psycho" refuses to definitively answer what made Patrick Bateman the way he is. It might be the materialistic environment he moves through, we guess, but also he might just have been born that way. "We Need to Talk About Kevin" similarly resists any easy answers, instead just letting us sit with that discomfort as Kevin's mother ponders those questions of nature vs. nurture.

The Machinist (2004)

Christian Bale's performance in "American Psycho" arguably made his career into what it is today, kicking off decades of physical transformations that would win him both fans and awards recognition. His body continuously seesaws between roles, and he's as apt to pack on muscle for "The Dark Knight" as he is to slim down considerably for "The Fighter." In "American Psycho," he sculpted his body just as Patrick Bateman did, getting his body fat percentage down into the single-digits.

A few short years later for "The Machinist," Bale lost a reported 56 pounds in just four months, according to Yahoo! He did this by reportedly eating nothing more than one apple and a can of tuna each day. (Starving himself, in other words. Do not do this!) The results are chilling.

"The Machinist" is about a man named Trevor Reznik (Bale) who is stricken with a severe case of insomnia, leaving him unable to sleep for over a year. The lack of sleep takes an incredible toll on his body, and as frightening as the jacked Bale was in "American Psycho," his gaunt, skeletal appearance in "The Machinist" is even more unsettling. Reznik is plagued by hallucinations and strange events, and as in "American Psycho," we are unsure how much to take at face value and how much might be the result of a point-of-view character utterly losing his grip on reality. It's a tense, uncomfortable ride, all thanks to Bale's too-committed performance.

Maniac (1980)

Though "American Psycho" was made in 2000, the film is set in New York City in the 1980s. It's about the yuppie culture that dominated Wall Street at the time, and its characters are a group of image-obsessed finance guys who care more about getting reservations at the right restaurant than they do, well, anything else. As a result, the film's scenes take place in high-end eateries, high-end office buildings, and high-end apartments.

William Lustig's "Maniac," on the other hand, represents the seedy underbelly of the same world Patrick Bateman inhabits. This film is also set in New York City in the '80s, but its locations are sleazier, and "Maniac" taps into the panic around crime that gripped the city in the '80s.

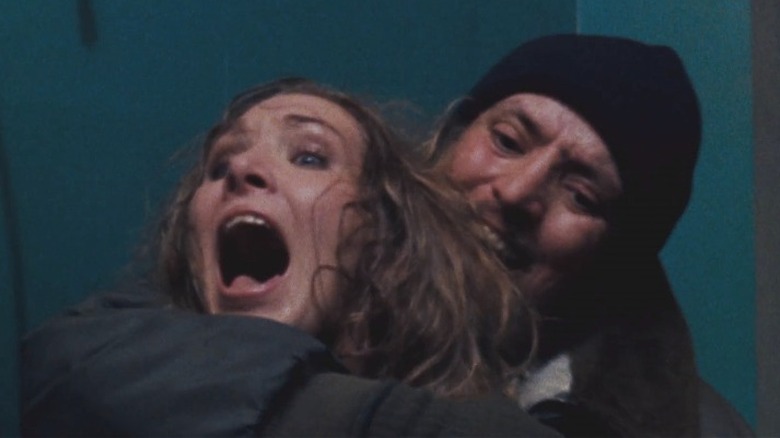

This, too, is a slasher movie whose lead character is the killer; in this case, he's named Frank (Joe Spinell), and he's obsessed with mannequins. He scalps women in his spare time to find new ways to dress his mannequins up, though he is also paralyzed by guilt and shame over what he does. He stalks the streets of the city at night, finding victims in locations like graffiti-covered subway station bathrooms, the shadowy streets underneath the Verrazano bridge, and in Central Park. It's all shot with some genuinely gnarly gore effects thanks to the legendary Tom Savini, who also stars in the film. Savini's death scene, involving a shotgun blast through a car windshield, is one of the most explosive kills in slasher history.

Maniac (2012)

"American Psycho" is a film that wants its audience to consider the value of aestheticized violence as entertainment, to wonder whether it says anything about us that we enjoy watching characters like Patrick Bateman behaving badly on screen. The history of horror is in fact full of films that want to make audiences feel complicit in on-screen violence. One common trick to accomplishing this is by including point-of-view shots, from the killer's POV, as they murder someone. The opening of "Halloween," for example, puts us right in the mask with Michael Myers, looking out through the eyeholes with him as he stabs his sister.

The 2012 remake of "Maniac," on the other hand, takes this conceit to new extremes. Nearly the entire film is shot from the serial killer's point of view. Elijah Wood plays Frank in this remake, the guilt-ridden mannequin-lover who is overcome with bloodlust at night and stalks the city scalping women. However, we mostly only hear Wood, save for the occasional glimpse in a reflection. Those reflections are important, however; as in "American Psycho," they allow us to look into the killer's face as he considers himself, wondering along with him whether there's a soul behind his eyes. And in this case, if we the viewers are what lurks behind the killer's eyes ... what does that make us?

The Snowtown Murders (2011)

"American Psycho" is a thrill ride of a film. Its pop soundtrack, bright colors, and over-the-top performances serve as a counterbalance to its darker themes. Still, it always places its violence in a socio-political context; Patrick Bateman basically wonders aloud how the pressures of the finance world have made him into the "entity" that he is today.

Justin Kurzel's chilling thriller "The Snowtown Murders" feels like the other side of the coin from "American Psycho" in many ways. Whereas Patrick Bateman's world is a world of high-powered rich guys, the characters of "The Snowtown Murders" live in poverty. It's a quieter film, one more concerned with emotions than theatrics, but it's no less effective for it.

The movie is about a teenager named Jamie (Lucas Pittaway) who falls under the sway of his mother's boyfriend John (Daniel Henshall), and they go on a killing spree together. Their murderous rampage seems like it's as much a lashing out against their socio-political circumstances as it is a result of any particular psychopathy or sociopathy. The movie is punctuated by extreme, shocking violence that the film refuses to look away from, even if it seems more interested in how the violence is affecting the characters who commit it. Like "American Psycho," perhaps the most chilling thing is that it doesn't seem to affect them very much at all.

THenry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

"American Psycho" is essentially a character study. There isn't much of a plot aside from a finance guy murdering a series of people, and somehow managing to escape consequences for his actions thanks to a world where everyone seems as indifferent to their fellow man as he is.

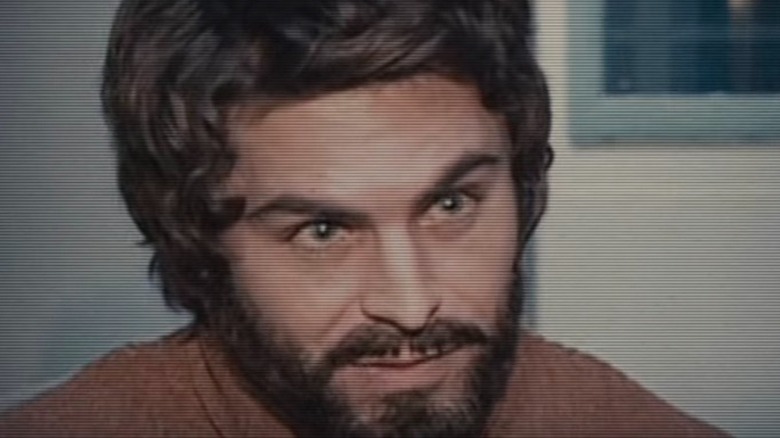

If you're looking for another character study — an uncomfortably-intimate portrait of a killer slipping through the cracks of society — you can't do much better than "Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer." Future "Guardians of the Galaxy" star Michael Rooker plays the titular Henry, who is inspired by real-life murderer Henry Lee Lucas, while Tom Towles plays his sidekick Otis, based on Lucas' protege Ottis Toole. If the real-life Lucas' confessions are to be believed (more than 600 of them, according to Time), he would be one of the most prolific serial killers in history. However, like Patrick Bateman, Henry has a slippery relationship with the truth, and he may be exaggerating just how many people he's actually killed.

Regardless of the real-life implications, "Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer" is a deeply-uncomfortable watch. It was a very low-budget film, shot with mostly amateur actors, but that style actually works in the film's favor. It makes the kills seem blunter and more brutal, rather than the pristinely-staged murders of "American Psycho." While this is a "portrait" of the killer, it's unsettling how the film refuses to let us into Henry's mind. All we can do is bear witness.

Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon (2006)

In "American Psycho," Patrick Bateman is obsessed with real-life serial killers. He frequently drops facts about killers like Ted Bundy and Ed Gein into unrelated conversations. While he doesn't explicitly make any reference to desiring fame for his actions, his obsession perhaps belies a desire to be among their ranks, to someday have his own name mentioned in the same breath as theirs. He likes fictional ones, too; he watches "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" early in the film, and "American Psycho" has its own iconic chainsaw sequence later on.

In "Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon," an upstart killer also admires legendary murderers. His idols are the slashers of horror movie infamy: Michael Myers, Freddy Krueger, etc. He wants to be just like them, to inspire fear the same way they did. "Behind the Mask" is a mockumentary, following Vernon as he attempts to get his reputation off the ground. It's a comedy, in other words, but there are effective horror sequences, too.

As in "American Psycho," Vernon narrates, walking audiences through his murderous plots step-by-step. Even though this guy is more pathetic than Patrick Bateman, it can be unsettling to hear murder described in such matter-of-fact, procedural terms. Successfully walking the line between black comedy and horror is what makes "American Psycho" so successful, and "Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon" makes for a solid pairing with the former film.