Was The Simpsons Matt Groening's Last-Minute Plan-B Pitch To Fox?

As of this writing, "The Simpsons" is 33 years old, which is, in TV years, closer to 110. The startling continued longevity of the animated sitcom has been enthralling to witness. The film will rise in quality, it will fall, it will rise again. It seems to be heading toward a conclusion, then throws open another curtain to reveal a further four-season plan. And still it lives, that keen and heavenward flame.

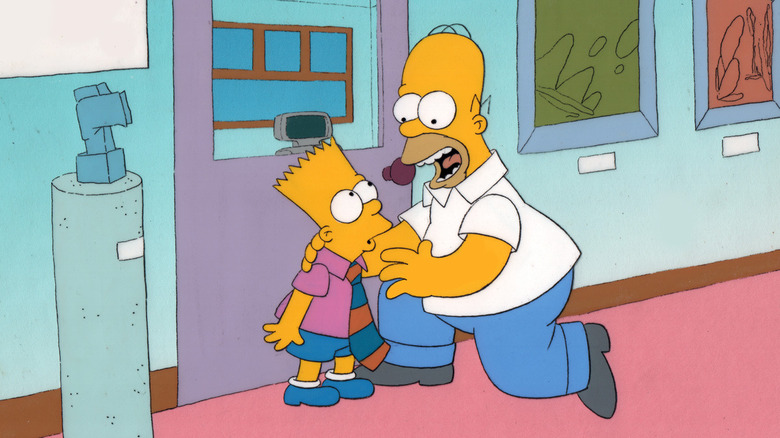

Due to said longevity, "The Simpsons" has transformed into an institution. It's difficult, then, to recall how revolutionary, how daring, and how subversive "The Simpsons" once was. It was an all-American sitcom, but skewed. The characters were yellow skinned, oddly shaped, and crass. They said "damn" on the air. They attempted to live a typical, clean, successful sitcom life, but were slaves to their grounded, base, below-average-ness. Bart (Nancy Cartwright) was a legitimate troublemaker who was proud of his underachiever status. Lisa (Yeardley Smith) was sensitive and intelligent and generally unappreciated. Marge (Julie Kavner) was a doting, overwhelmed who would drink at work functions and fail to get a handle on the home she so desperately wanted to domesticate. And Homer (Dan Castellaneta) was initially a working-class boob who longed for his family to be The Waltons, but shriveled at his continued lack of success. Homer seemed to lose 10 I.Q. points with every progressive season, and eventually lost his ability to perceive the world around him accurately.

These characters were the vanguard of a new age of raucous, critical 1990s cynicism, meant to topple the corporate-driven, conservative ethos of the 1980s. Ironic that they are still, to this day, a marketing bonanza. That "The Simpsons" is now owned by Disney reveals how far behind us its anti-corporate, satirical ethos actually is.

Life in Hell

It's worth remembering where "Simpsons" creator Matt Groening was prior to the series. Since 1977, Groening had been authoring a darkly bitter comic strip called "Life in Hell," published in counterculture papers all over the United States. "Life in Hell" was a regular analysis of the more stifling, embarrassing, and ... well, hellish aspects of life. Love was hell. Work was hell. School was hell. Childhood was hell. The strip's regular characters included the rabbit Binky, his sometime love interest Sheba, the one-eared rabbit child Bongo, and a queer couple named Akbar and Jeff who looked identical and wore fezzes. It was a legitimately edgy, sometimes surreal strip rooted in a deeply felt disappointment in life.

One might intuit correctly that Groening, perhaps definable as a proto-Gen-Xer, was suspicious of the commercial corporate world. As such, when it came time to sell his art to the corporate world, he had to pivot at the last minute.

In "Icons Unearthed," a video documentary series put out by Vice, author Chris Turner of the 2004 book "Planet Simpson: How a Cartoon Masterpiece Documented an Era and Defined a Generation" – talks about how Groening was all set to pitch "Life in Hell" to the corporate overlords, but, in a flash of suspicion, pulled it back. Who, he began to wonder, was going to own this? Turner tells the following story:

The Groenings

"Groening, you know, is getting ready to go in and pitch his idea for a show, based on 'Life in Hell,' when it occurs to him that if he pitches successfully he will no longer control his own creation. It'll be, you know, property of Fox or whatever. And Groening, coming from this, you know, irreverent, underground cartooning, alternative universe, is deeply suspicious of corporate influence and corporate control, decides more or less on the spot, 'No, I'm not pitching them 'Life in Hell.' I'm gonna just go in the entirely other direction. I'm gonna quickly draw, you know, this sort of sketch.'"

The pitch he came up with at the last minute was his own family. In real life, Groening's father is named Homer, his mother Margaret, his sisters Lisa and Maggie. He stopped short of naming the Bart character "Matt." His mom sported a beehive hairdo. His grandfather was named Abraham. The hastily conceived idea was that these characters — the Groenings — were going to be stars of their own sitcom. But something that wouldn't be too far from the spirit of "Life in Hell." As Turner put it:

"[Groening] sketches a mom, a dad, and three kids and then goes in and says, 'You know, what we should do is the family sitcom family from hell.' And that's where 'The Simpsons' was born."

It's a romantic, fun story. It might also not be true.

The REAL origin

The documentary also interviews Ken Estin, one of the executive producers on "The Tracey Ullman Show," who recalls the inception of "The Simpsons" a little differently. "The Tracey Ullman Show" was where "The Simpsons" had started their life, appearing as an amusing animated break in between the show's live-action sketches.

Estin had hired Groening to make a 60-second "Life in Hell" short as an interstitial on the show, and was sent off to write one (1) joke. Groening never turned in the joke. It wasn't until Estin called an intermediary that he learned Groening's mindset. While Groening would retain creative control of "Life in Hell," he would have to share merchandising rights, which was how he was making the bulk of his income at the time. "He's keeping it to himself and he's not going to share it with anybody," Estin said. When he didn't turn in anything, Groening was fired.

Future "Simpsons" honchos James L. Brooks and Richard Sakai, however, eventually chimed in, saying that they would take anything Groening put out. It didn't have to be "Life in Hell." Estin says that it was then, after he had already known he got to keep "Life in Hell," that Groening finally pitched "The Simpsons." Whether or not he came up with the characters on the spot can remain speculation. A few days later, the first rudimentary scripts were written.

Groening himself, meanwhile, has never come clean on the matter.