The Good Nurse Writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns On The True Crime Story And Lessons From 1917 [Exclusive Interview]

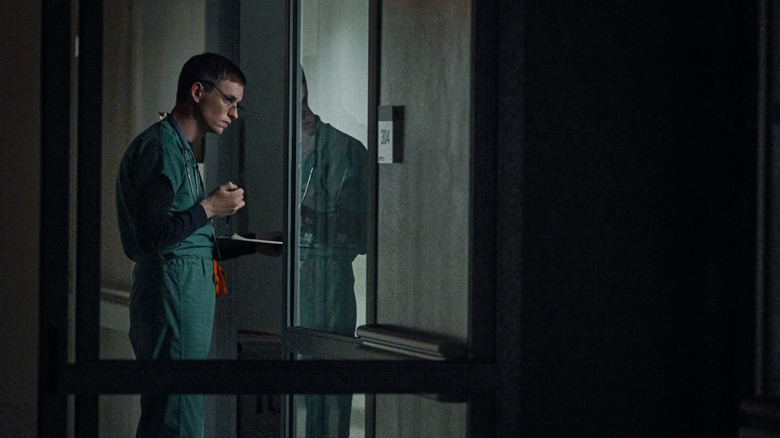

Jessica Chastain plays the titular character in "The Good Nurse," which is not an ironic title for the true crime story. Based on Charles Graeber's book, nurse Amy Loughren (Chastain) discovers her friend, Charlie Cullen (Eddie Redmayne), is murdering patients. It's a horrifying story that screenwriter Krysty Wilson-Cairns initially wasn't interesting in telling. Once she read Charles Graeber's book about the case, though, she had to write the screenplay, which was eventually directed by filmmaker Tobias Lindholm.

Krysty Wilson-Cairns is the Academy Award-nominated screenwriter behind "1917." Over the last few years, she co-wrote "Last Night in Soho" and also worked on "Penny Dreadful." She's a standout writer for a variety of reasons, including the fact she's often on set collaborating with the directors. It's a rare experience she recently told us about in an interview about "The Good Nurse," her past work, and letting actors act.

'I had no idea how to tell the story until I reached the final third of it'

When you started working on this script, did you discover it's a story not many people know?

I had never heard of it, and I'm the kind of person that's up late at night googling serial killers. So it's always surprising to me that I had never heard of it when I first read Charles Graeber's book. And then I spent a lot of time in New York and in Connecticut and in New Jersey doing the research. Almost everyone I met hadn't heard of it or were like, "Oh, I think I saw a news article about him 20 years ago, but I didn't know he killed that many people." There was a real lack of the facts. And I, as a pessimist, think that's more about the American healthcare system covering its tracks than it is about people not having access to it.

You tell the story from Amy's perspective, not Charlie's. Was it like that in the book?

Well, the book takes place very intensely over the 16 years that he was killing. But it has sort of Charlie's entire lifespan in it, because the author, Charles Graeber, he is meticulous with his research, and actually had access to Charles Cullen. So there was a huge amount of Charlie in the book. The book is laid out almost like a law case. It's, "Here's evidence, here is a theory, here is a conflicting theory." It's built in this way and it becomes totally riveting and absolutely thrilling.

I had no idea how to tell the story until I reached the final third of it, in which you meet the real Amy, Amy Loughren. It was the moment that I was like, "Oh, of course this is the way in. This is the person that we see the killer through." Because I think it's hard to write a movie where the killer is the center of the show, is your window in, because you have to make so many assumptions, first of all, about why he did it, which we don't know and we can never really know. And second, you either glamorize them, or you make them a sort of antihero. I think it's very difficult to do that without fetishizing it. I had no interest in that. I don't really respond well to any of those elements of true crime.

For me, following Amy and seeing it from her point of view, being locked into her perspective and learning it in drips as she did, I thought was the most thrilling and the most structurally sound way to tell it.

Her own health crisis, as well, brings a lot of suspense to the movie.

Yes, I don't come from a place where we have healthcare for profit. I come from a place with socialized healthcare. So a lot of that was a huge learning curve for me. I had Charles Graeber's book. I also had all of Charles Graeber's research and I had him, which was a fantastic resource. I also met the cops and I met the real Amy. And that was where I really, I think, got the most out of everything, because she allowed me into that time period of her life.

She totally laid that bare, what she was going through and what it felt like and how she worried that she was going to leave her kids without a mother, and how she was working herself to death, hoping that she could work long enough to get healthcare, that she could then solve her very serious heart condition. You couldn't make that up. That can only happen in real life.

'The audience can s*** themselves, hopefully'

The movie does play like a psychological horror movie. Did you approach it that way?

Yeah, I think it's one of the scariest horror movies because it's true. And also, because one of the villains has been caught and is behind bars, but the other villain of the piece, the healthcare system, the structure that we all live within, is still out there and rife and I think desperately need overhaul. I think all of that makes it incredibly scary. The book kept me up at night. When I first started reading it, I sat to read one chapter, to politely decline, because I didn't want to write a serial killer movie. And then I read the whole book in one sitting. It was absolutely terrifying. It was terrifying that this happened.

You mentioned you were apprehensive to write a serial killer movie, and there are elements of true crime stories you don't like. How'd you want to tell Charlie's story going beyond what we usually see from true crime stories?

I think there's a tendency with true crime, and even with us as people, to make these men and these women do these heinous crimes, to make them "other." To put them away from you, or to find a reason that they do it. So it makes you feel safe. You're like, "Oh, that is why that happened." Or, "They are demons." Or, "They're evil." I think the truth of it is that there is humanity in Charles Cullen, and that made him so much scarier because he was her best friend. And I do genuinely believe — and I believe because that's what Amy told me — that he was a good friend. He helped save her life. And I don't think he was acting, I don't think he needed to act.

So, if you weigh up that duality, I think you become totally mystified by it because it's so hard to grasp. But you also have a feeling of like, "Well, what is this? I can't really look away because parts of me are in there." It is the human experience that Amy went through. What I also love is he wasn't defeated with violence. Charles Cullen wasn't bullied into a confession by two big cops. He confessed because Amy used her humanity to remind him that he was human and to make him do the right thing. That's the only way he could ever have been stopped.

We always are, especially in film and TV, we're stuck in the cycle of violence stops violence, but in reality, that's not always the case. I think we need to move more towards that with this idea of, "Can humanity, can empathy, can understanding stop violence? Can it help us repair our broken systems?" And as a writer, when you get this kind of material, you have to pinch yourself a lot. And I basically spent 10 years pinching myself.

Did you often find you really didn't have to heighten elements for cinematic purposes?

This was my first paid job, so I've probably been doing this for close to a decade. I think in the first iteration it was more like "Silence of the Lambs." It was more arch and more horror. And then as I came to get a real grasp on the story, and as [the director] Tobias came on board, we really then began to understand that the scariest version is the truest version. If we can invent almost nothing, and we can stand by this film and say, "This all happened," I think then you get real thrills. And it has so little violence, which, for a serial killer movie, is rare.

I think when you see it, sometimes — there's that scene in the diner where he slams his hand on the table. I've watched that in cinemas full of people and everyone jumps. And it's because these suggestions of violence, I think, are powerful. I think they're more akin to our life and how things really happen.

I was pleased when Tobias came on board and we were aligned in, "Hey, let's make this truthful. Let's make this feel real and incredibly domestic." And through that, the audience can s*** themselves, hopefully.

It's kind of like how in "Zodiac," there are these brutal, horrifying scenes, but it's also terrifying because of the lack of answers or, as you put it, the threat of violence.

To me, the scary scene in "Zodiac" is when he is in that guy's basement and nothing happens. There's no violence, but there's this suggestion of violence. You know there's the capacity for violence. I think that's what Eddie [Redmayne] and Jessica do so beautifully in those scenes, is that you are aware that there is the capacity for a great evil. But you can't see it. Even when you're looking for it, you still can't see it.

'I am perfectly happy to turn around and say cut this scene'

You were on set for "The Good Nurse," similar to "1917" and "Last Night in Soho." That's rare for screenwriters. What do you find beneficial about being on set?

I've been three for three. I was on the set for "1917" every day, the same with "Last Night in Soho” every day, and with this every day. I really push for it. The reason I feel safe to push for it is because I have a great relationship with the directors I've worked with. "The Good Nurse" was no different. We started working together on this six years ago, where he would be in Copenhagen and I'd be in London, and we'd Skype three times a week, and we became collaborators, but also friends. There's a huge amount of respect between the two of us. There are a lot of things we do similarly and a lot of things we do differently. I think we mesh well as a couple of opposites.

The reason that I love being on set, if you can help in any way, shape, or form, and if you can keep your ego in check and if you can keep in mind this is a script that you wrote under ideal conditions in which everything goes right, and now we're in reality and we have to get the intention — not necessarily the whole scenes, but the intention of the scenes, we have to understand what's come before and what will come after so that you can essentially help this movie pull itself together, I think it's always useful to have a writer there because it's the last fail-safe for the story.

I am perfectly happy to turn around and say, "Cut this scene, but these three moments that happen in this scene make sense. In the long run, you can reference these three times. So, hey, do you mind if I go and put them in these other scenes?" I think it's really important to have that.

I think it spares the director another job. It's not easy to be a film director. There's a lot going on, and there's a lot that you have to try and master, and there's a lot of decisions that you have to make in the snap of the moment. Being able to assist in that in any way, shape, or form, I think earns your keep.

I don't even get paid to be on set, they just have to feed me craft services. So I think I'm a steal. You get to be there, you get to see it come to life, but you also get to help people. And when lines don't work, you get to rewrite them, and you get to work with the actors really closely, and through that process really understand the characters that they're portraying, and then direct the scenes that are yet to be shot into those characters. I think you end up with something a lot more cohesive and a lot more collaborative than if you just stay at home and don't get up before 10:00 AM.

Being on set that much, has it changed how you write?

Yeah, massively. I think every experience on set has been hugely informative and foundationally adds to anyone's ability as a writer. For me, from "1917" all the way through, I've been so fortunate, and a lot of what I learn is that you can take so much of the dialogue out and you can just let the actors act, because they're f***ing great at what they do. They can do it with their bodies, with a look, which would take me pages and pages, and they can do it in a way that's so much more immediate. What is it they say? 90% of communication is body language, non-verbal. Real actors understand that and know that.

One of my favorite things to do on set is to go to the director, "We don't need those lines." It's so liberating. Sometimes there are lines I've spent 10 years on, and I really like those lines, but this is better. I mean, it is a real privilege. The big thing is let actors act. You don't need to write the 16-page scene; do it in two pages if you can, and let there be silence, let there be emptiness. Let there be this vacuum that people pour themselves into. I wish I'd known that when I was born.

'The one in the asylum is unf***ing real'

"1917" was such a massive undertaking. When you climb a mountain that high, how else does that change you as a writer?

Weirdly, I wrote this film before I wrote "1917," and then I also wrote it after I wrote "1917," because "1917" basically came together in two years. Everything happened from the first phone call with Sam and I right through to the Oscars. It all happened in this very short window.

I always believe that you have to write visually and then having to write "1917" meant that you have to write beyond your capabilities of visual writing. It's lovely to work with Oscar winner Sam Mendes, and to see how he builds that. And to work with Oscar winner Roger Deakins and his wife, James Deakins, and have this ability to understand the visual language of cinema and what can fully be achieved when people are unbelievable at their jobs.

Now, I carry that through everything. So I probably rewrote "Good Nurse” after working on "1917," and I probably understood visuals and how to write a cut, and how to almost shepherd a scene in your mind, and then you add to it, and add to it, and add to it.

It's the same with Edgar [Wright] and "Last Night in Soho," and his ability to literally edit in his mind as he's shooting, as he's going. Watching and learning that at the same time, it informs it so that you know when you're watching the scene get shot, you're like, "Well, those lines aren't quite right, but we're not going to use that wide. We're probably going to use the close up. Okay. We've got time to change them." It's all fodder for the machine, and the machine is just someone who likes to make films. [laughs]

As for television, you worked on "Penny Dreadful," which was a great show. When you were writing on that series, did you know the ending [creator] John Logan had in mind? Was that the ending always planned?

We didn't know if it was going to go for a fourth season or not. We were waiting, we were working it all out. It was a long time ago. I'm trying to cast my mind back, but I think we knew that Eva Green wanted to end her arc, but I don't know if we had fully decided if the other characters were going to carry on. Ultimately, that was John Logan's call in the end, because this was his life's work. It was everything that he loved, boiled down.

It was such an unbelievable job to work on with him, and to sit at his right hand and to learn from him, who is the master. It was really formative for me. But yes, he would know all. I think as far as I know, we were like, "Let's make sure that we don't close doors that we don't have to close, and let's see what happens and what goes." Because there was so much love for that show, myself included. I was a fan before I worked on it, and there just felt like so much life in it. And that's such a testament to John and his brilliant imagination.

Some of the best bottle episodes, especially with Eva Green.

The one in the asylum is unf***ing real. I remember reading that script and being like, "What the f***? How do you even do that?" Andrew Hinderaker, who's now the showrunner on "Let The Right One In," it was just the three of us in the writers' room. We would sometimes look at each other after reading John's episodes and be like, "How did he do this?"

Are we going to see you direct sometime soon?

I don't know. I just started producing, one step at a time, and got my own production company. Never say never. I've got a lot to learn first. There are a lot of very fancy directors I want to work with, and some fancy directors I want to work with again.

"The Good Nurse" is now streaming on Netflix.