William Friedkin's Biggest Influence On The Exorcist Was An Obscure '50s Danish Drama Film

Few movies have the diabolical aura of "The Exorcist," and much of its reputation comes from its sensational and controversial release almost 50 years ago. William Friedkin's film had people queuing in the streets to see what all the fuss was about, as tales of moviegoers vomiting or passing out in theaters only served to emphasize its devilish allure. Critic Andrew Sarris of The Village Voice even went so far as to call it "a thoroughly evil film." Then there were the predictable rumors of an on-set curse and the subsequent ban in the UK, all of which added to its stature as one of the most frightening mainstream horrors ever made.

Despite its whiff of sulfur, I never saw the film as anything remotely evil. I approached it with caution at first but I consider it a good film in the purest sense of the word. Sure, it catalogs the vile degradation of a young girl in vivid and upsetting detail, but that is not the primary focus. Instead, it is about good people having the courage to confront violent phenomena despite their weaknesses and self-doubts. What always strikes me is that neither priest goes into the situation 100% convinced that God has their backs; one is old and dismayed by the evil in the world, while the younger is suffering a crisis of faith.

I've always thought of "The Exorcist" as a metaphysical western, a white hats vs the ultimate black hat confrontation, with an aging gunslinger character riding in with his fallible partner to save the day, and paying with their lives. It is a film about faith and the resilience of goodness in the face of evil, and Friedkin presents his themes as absolute truths. For this approach, he turned to a heavyweight of arthouse cinema for inspiration.

So what happens in The Exorcist again?

"The Exorcist" opens in Iraq, where elderly Catholic priest Lankester Merrin (Max von Sydow) is visiting an archaeological dig. He encounters an ancient statue of the demon Pazuzu and watches wearily as two dogs fight viciously, seemingly disheartened by the evil in the world. This ties in with my western analogy as Merrin and the statue face off across the windswept rocks like two cowboys locked in a showdown.

Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., actress Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) is in town starring in a film directed by her friend Burke Dennings (Jack MacGowran), and has just moved into a luxurious house with her daughter Regan (Linda Blair). We also meet streetwise local priest Father Karras (Jason Miller) who is suffering doubts about his religion after the death of his mother.

Chris hears strange noises in the attic and Regan starts acting unusually, talking about an imaginary friend and wetting herself at a housewarming party. As her behavior becomes more aggressive, she undergoes a series of medical tests which turn up blank. The situation becomes critical when Dennings, left looking after Regan one evening, is found dead at the bottom of a steep flight of steps outside the girl's bedroom window. Movie buff detective William Kinderman (Lee J. Cobb) is assigned to the case.

A doctor mentions exorcism as a possible solution and Karras visits Regan. The demon possessing her abuses him with foul language and taunts him about his deceased mother. As the phenomenon worsens still with horrific physical effects on Regan, the priest consults his superiors to sanction an exorcism, and Father Merrin arrives to perform the ritual.

The Danish masterpiece that inspired Friedkin

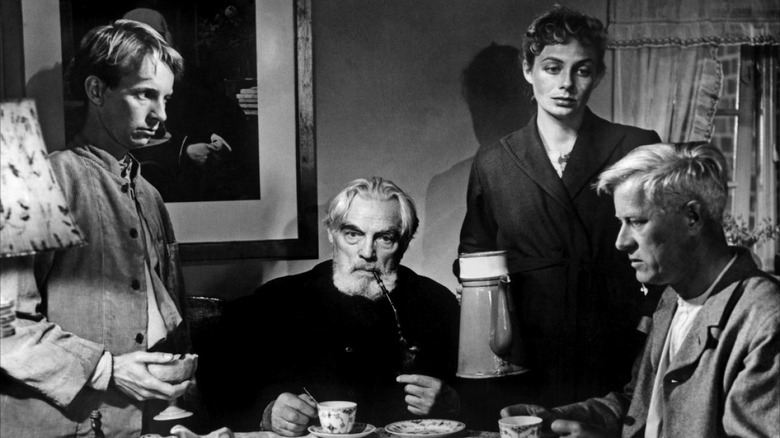

"Ordet" ("The Word") is one of the big guns of European cinema, usually riding high in critics' lists of the greatest films ever made. Directed by Danish master Carl Theodor Dreyer, best known for "The Passion of Joan of Arc," it is not a film approached lightly; indeed, it's a film so heavy that it has its own gravity. That is to say, a patient viewer who makes it past the film's austere opening movements will likely find themselves locked in its grip.

Like "The Exorcist," "Ordet" is a film about faith, focusing on two Christian families headed by stern men who disagree vehemently about whose version of Christianity is best. The family members range from an atheist to a seemingly insane brother who thinks he's Jesus Christ. His illusions are proven false, provoking a crisis of faith, but he still manages to perform a miracle at the end of the film.

With its sparse sets and funereal pace, it can take a while to adjust to the film's rhythms. The characters talk slowly and deliberately, often positioned in the frame facing in different directions while having their grave discussions. At times it looks like a skit parodying depressing black-and-white Scandinavian cinema.

I went into "Ordet" expecting boredom, and it was touch-and-go for a while whether I would persevere. About halfway through, I decided that I really loved these characters, but it was Dreyer's filmmaking that kept me going to that point. He only uses 114 shots in total, some lasting several minutes, but the film is not static in the least. With meticulous blocking and intricate lighting, the understated grace with which the camera moves within those shots is an absolute masterclass.

Why Ordet was such a big inflluence on The Exorcist

Regarding the influence, Friedkin told EWTN:

"The most spiritual movie I've ever seen is called 'Ordet' by Carl Theodor Dreyer. It shows a literal resurrection, so believable. I saw this movie years before I made 'The Exorcist,' and I knew because of that film that I could show a literal exorcism. I could show it literally not as some kind of a horror film. Dreyer approached the theme of the miracle very directly... That is how I wanted to approach the theme of exorcism. So I thought a lot about that film while I was shooting mine."

That makes total sense when you compare the two films. In "Ordet," the miracle occurs after a mother dies after complicated childbirth. Johannes, the man who thinks he's Jesus, finds resolve in the blind faith of the woman's young daughter and brings the deceased back to life. The resurrection is handled with simple conviction and, after the solemnity of the rest of the film, illuminates like a ray of divine sunlight piercing a foreboding cloudscape.

For "The Exorcist" screenplay, Blatty stripped away the scientific alternatives he offered in the novel, leaving Friedkin to present his exorcism in a plainspoken, uncritical manner, observing the ritual with almost documentary-style rigor.

Dreyer was not a particularly religious man (via Roger Ebert), but he treated his pious characters with the utmost respect. Friedkin has said he is a believer, and he transmits that belief to his film. Both directors are completely earnest in their approach and whenever I watch "Ordet" or "The Exorcist," my skepticism is suspended and I find myself believing for a few hours, too.

Does The Exorcist still hold up?

For all its infamous scare tactics, "The Exorcist" works best as a study of faith under extreme duress, and Friedkin treats the subject with the utmost sincerity. Although some contemporary critics wrote it off as a lurid shocker it is anything but; this is a serious film with discussing age-old questions, reflected in the fact it was the first horror to receive an Oscar nomination for Best Picture.

Nowadays some of the special effects look a bit creaky, which unfortunately renders some scenes unintentionally comical. When I watched it with friends who hadn't seen it before, the head spinning and the projectile vomiting provoked laughter instead of terror. As usual, the Devil gets all the best lines, and Pazuzu, voiced brilliantly by Mercedes McCambridge, shows a sly and extremely dark sense of humor during its interactions with the priests.

The performances are all top-notch. Blair is convincing as a happy 12-year-old before undergoing horrific changes and Burstyn is incredibly sympathetic as a strong single mother who becomes increasingly desperate watching her daughter consumed by the evil force. Von Sydow brings the gravitas you would expect, but the best of the bunch is relative unknown Jason Miller. It was the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright's first film and his lean, haunted performance endows his key role with terrific power.

"The Exorcist" is the middle film of an incredible hat-trick from Friedkin in the '70s, coming between "The French Connection" and the unfairly overlooked "Sorcerer." His direction is flawless, although he reportedly resorted to unorthodox methods to get the performances he wanted. He fired a gun with blanks on set the keep the cast and crew on edge and slapped the real priest who administers the last rites to Karras to elicit a convincingly shaken reaction from him.