Sophie Jarvis Explores The Rot Beneath The Beauty In Until Branches Bend [TIFF Interview]

Early into "Until Branches Bend," the finely wrought first feature from writer/director Sophie Jarvis, Laney (Alexandra Roberts) says to her sister Robin (Grace Glowicki), "There's more to life than Montague," the small town where they work as line inspectors on a peach farm. "I know that," Robin quickly retorts, not realizing how big and how complicated life is about to become.

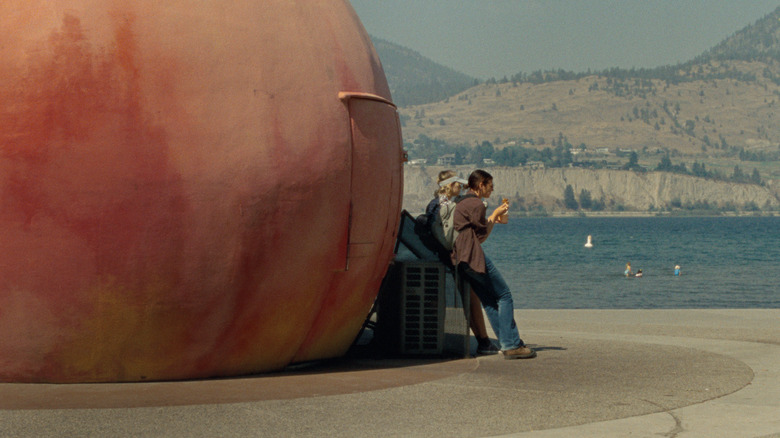

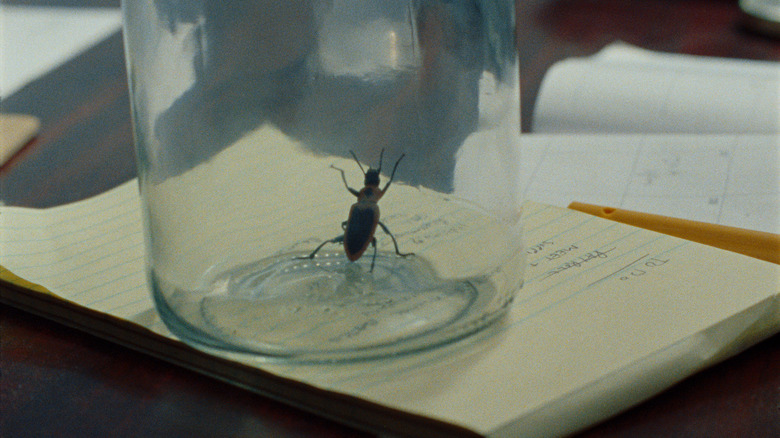

Robin leads a quiet, dutiful existence in the pastoral Okanagan region of British Columbia. She drives herself and Laney to the cannery each day in her beat-up truck, politely socializes with the other inspectors and pickers while she performs her mechanical labor, and goes home at the end of each long day to take care of her black standard poodle, Rupert. But a rotten wormhole spotted within a peach on one day's off hours throws the entire community into upheaval. Robin becomes a reluctant whistleblower when her boss, Dennis (Lochlyn Munro), refuses to take action about the potentially invasive insect found inside. Unwanted pregnancies, fractious local politics, and the murky ethics of agribusiness swirl together, threatening to tear Robin asunder.

"Until Branches Bend" is a superbly mounted effort from Sophie Jarvis, whose shorts range from the serious to the slapstick, from animation to a kind of kitchen sink realism, and so on. With this first feature, she's found a preternaturally assured voice with which to tell a story of haunting allegorical power — what feels like an elder passing down the wisdom of the generations. I sat down with Jarvis ahead of the World Premiere of "Until Branches Bend" at TIFF to talk all things monoculture, transitioning from production design to directing, and shooting in the Okanagan.

'She's just a terrific clown'

Congratulations on having your first film selected for premiere at TIFF. You must be so excited.

Oh god, I am. And so nervous. Thank you so much. We finished the film just before we had to deliver everything for TIFF, which was great because we had a lot of momentum coming out of post. And knowing we had a world premiere secured was nice, knowing we didn't have to hit the ground running.

This is your first feature as a director, but you made several short films before this.

Yeah, I've made a lot of short films since I finished film school 10 years ago, which is actually nuts, because my first short film, "The Worst Day Ever," actually premiered at TIFF in 2012. So I feel like there's a real full circle moment happening here, 10 years later. I've made a lot of stuff that's driven by, basically, my own curiosity. I like to learn a lot. So a lot of these shorts were made because I wanted to try something new, either it was a storytelling thing or a materials thing. For example, I also just finished this stop motion animation short this year, which has nothing to do with this film. I feel like short films have been like a really great play area for me to mess around in while trying to get my features off the ground.

It makes sense that you saw your shorts as opportunities to explore different ideas and media, because this film has this surprising tonal complexity to it. The images are naturalistic, but the score is kind of surreal, and there's also a good deal of humor.

You just made my day by saying that you found it humorous because I think that on the page the script could have been interpreted as fairly dramatic, edging even on melodramatic. And I'm just not really that type of person. I find a lot of comedy comes from subverting what people are expecting. I wouldn't say I intentionally go out trying to subvert people's expectations — it's more just seeing those opportunities for reversal and digging into them in whatever way feels right.

So for example, the lead, Grace Glowicki, I mean, she's just one of my favorite actors, but I think that she's just a terrific clown, if you know what I mean. She's in complete control over her own physicality, and her way of working is very in the body. She's also a very funny person. So she was able to play this character who is pretty intense and lacking in humor in a way that to me is very funny. But she also plays Robin with a lot of empathy and compassion. It makes me happy to hear you saw the humor. I think that every choice I make has this subtle edge of absurdism that I feel very comfortable in. That's in the score, and also sometimes in how we frame things, and also in the interactions that happen around the characters.

'A natural place for something to go wrong'

The landscape also felt prominent in the film, the location. Could you discuss the role of the Okanagan region where you set the film?

Well, it's funny, my grandfather, who was Swiss, actually moved from Switzerland to a town called Summerland in the Okanagan in 1965. Growing up we went to Summerland all the time. It's a place that just really feels like home, but I'm an outsider. Do you know what I mean? I grew up in Vancouver, which is technically just a drive away, but it's a world apart. Going to Summerland was always a big event. This is a place that has four seasons in the summertime and is an orchard town, stone fruit is such a big thing there. My grandpa wasn't a farmer, but he had a lot of fruit trees, so I'll never eat a peach and not think of my childhood growing up there. To me, it's a place where even from my mom's stories, nothing bad ever seemed to happen. So in my own sick, twisted way I thought, this place that to me feels so idyllic and also looks so idyllic seems like the perfect setting to poke a few holes in it and see — what could happen in a community like this and a landscape like this to make things go awry?

My mom actually worked in the cannery in Summerland when she was a teenager. She told me a bit about it and how it was just like this great place where teenagers, housewives, so many different generations and cultures of people were working there together. I was inspired by her telling me those stories and thinking, okay, there's the farmers, but there's also the factories. And there are so many people who are intricately linked to farming here and to fruit. That seems like a natural place for something to go wrong.

You depict in the film how the community in that area really is so dependent on the crop, on the harvest. How if one thing were to turn the entire community would be in jeopardy.

Yes, and it's not unlikely. We did so much research for this film, years of research. The beetle actually was inspired by a bug called the coddling moth, which was a huge problem for over a decade in the Okanagan. There's a research station in Summerland called the Summerland Research Station where the scientists are kind of heroes in the community because they were the ones who developed a very simple, but also extremely effective eradication program. A lot of farmers lost their farms, a lot of people went bankrupt because of this moth that attacks the apple trees. But because of the sterilization program that the scientists came up with, it was this very simple way of just breeding moths in the lab as a way of rendering them sterile, and sending them out into the world to mate with wild moths.

The way they tracked the spread of infertility, which I totally stole for the film, is they fed the moths an all-pink diet at the lab. So when you squish the moths and see that they're pink inside, you'd know that they're sterilized. It's a really a kind of incredible system. You'd think it would be very complicated, but in the end they just fed them pink and sent them on their way. And you know their funding is garbage, scientists don't get any money. So they have to make do with stuff they can find at Home Depot. It's the most amazing thing.

Anyway, there was a lot of research done about that, a lot of research talking to orchardists and farmers, the local first nations as well as white settler families, and also immigrant farmers, you know there's a lot of people who came from the Punjabi region in the seventies. We made sure to really get our understanding of that region and its complexity right, because everybody there is part of the community, and it's a small community.

'What humans and the society we've created have done to the land'

On the note of that complexity, the film builds to the revelation of these awful irreconcilable oppositions. In order for the farm to provide jobs for the entire town, they have to overwater, practice monoculture, and spray pesticides. But the pesticides are causing cancer in Okanagans, and monoculture is destroying the local biodiversity. So then you get these bugs that come, but if you point one out everyone loses their jobs, and if you don't, the people you're shipping the fruit to could get sick. It's like no matter what choice is made someone loses.

Well, first of all, as a filmmaker from Vancouver, I'm extremely qualified to speak about a farming community like Summerland [laughs]. But seriously, I grew up visiting Summerland as an outsider. So like I said, I had to do a ton of research to make the central scenario in the film accurate and believable, and one of the things I discovered from all the research is just, there's no one person to blame. You see that in the film. The closest thing you get to a "bad guy" is Dennis, Lochlyn Munro's character. But Dennis points out in the town hall meeting that the farm is a cooperative, and he is really just fighting to have people keep their jobs, even if that does mean lying about Robin. Like the workers, he's also just doing his job, which he sees as a service to the greater community.

Ultimately it roots down to what humans and the society we've created have done to the land. And I would say that that comes with colonization, because the issues that we're seeing in the Okanagan these days are directly due to human interference. Monoculture farming in particular is a huge part of that. You know, we have these wildfires every year now, too. It's brutal in the summer, there are so many issues every year. It's the decisions of a few humans along the way and now everyone's just caught up in it.

And Robin herself, as much as Lochyln Munro's character isn't the villain, Robin isn't a typical protagonist. It's not like she's Erin Brockovich, crusading for what's right. Throughout the film, people are like, "Why are you doing this?" And she doesn't really know, she even wants to take back what she did.

She wants to retract her choice immediately.

Right. Her character feels so realistic, was it a matter of working through a number of drafts to make sure Robin wasn't a flat character?

If you can believe it, she was actually way more ambiguous in my early drafts. When you make a first feature that actually has a budget, you get a lot of people weighing in on the script before they will give you the money. And a lot of the notes I got were to make Robin, for lack of a better word, more cliche. I was able to take many of those notes and find other solutions, ultimately, even notes that you don't like are rooted in something that needs to be addressed. I would say that her character came to the place where you see her now because I resisted the encouragement to make her more conventional.

Even with her pregnancy, I had her be a bit more on the fence. In the back story we developed for Robin, she's basically always been a caretaker for Laney. She's been taking care of her since she was 18, so she's been a kind of parent her whole adult life. In very early drafts of the script, I saw her as being kind of on the fence about getting an abortion because in one way, she's used to being a parent. So it would be kind of the safe thing to do. In another way, I think her heart doesn't want to continue doing that. That was a really important change that I made to the script. There was stuff I thought was stronger that I wanted to focus on that ended up having more parallels to things that are going on in our world. Writing is just a process of finding out who your characters are and figuring out what they're like. The Robin from the early drafts would be a total stranger to the Robin in the film.

'Those dead bugs — all real'

There is a scene toward the end of the film where Robin is riding down a dirt road in a truck, and the camera is mounted on the hood shooting through the windshield, which is just covered in splattered dead bugs. When I read after the film that your training is as a production designer, it made total sense. Is this the first film where you've ceded production design to a team you're not on?

Well, I would love to take credit for that detail but actually, that was just the truck of our set decorator Courtenay Mayes. She had just been driving it around the Okanagan, and by the time we shot that scene it happened to be completely splattered by bugs, which felt perfect. So those dead bugs — all real.

But yeah, the production design team is almost all people who I have worked with before. This was my first time working with Courtenay actually, but the production designer was Charlie Hannah, our art director was Kara Hornland, who I've worked with on so many projects. The props were done by Mona Fani, and all of them are also artists in their own right. They're all people who are photographers or they're stylists, Kara is also a movement director, so she did the movement direction for this film as well.

I think what I love about production design is it brings in so many talented people, and there's a place for everybody. Even with a project like this, which was an independent film, you can bring together this great group of people who all have different skills. I was lucky because as a production designer, I'd worked with all of them. So they all knew me really, really well and understood my taste. So I felt like I was in very good hands because you know, it can be a bit hard to step away from what you know best when it's your own project.

"Until Branches Bend" had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on Saturday, September 10, 2022.