The Rise Of Self-Awareness In Cinema: Is Film Doomed To Become A Mockery Of Itself?

Cinema has entered a new dawn. It arrived a while ago, actually, and you may not have even noticed.

I'm not referring to the recent surfeit of remakes, sequels and adaptations, or the rebirth and subsequent profusion of superhero movies, or even the resurgence of 3D. No, I'm talking about the evolution of a burgeoning subgenre in cinema: meta films, aka movies about movies. Whether you've seen it or not, these self-reflective satires, parodies and homages have become a recurring staple of the aughts, and slowly but surely, the landscape of modern cinema is changing because of them.

For evidence of this, look no further than six of the major releases of the past month. We've got: The Expendables, a tribute to the testosterone-filled macho-men movies of the '80s; Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, an all-encompassing satirization of movie tropes going as far back as the Shaw brothers films of the '70s; Piranha 3D, a sleazy horror throwback to '70s/'80s exploitation; The Other Guys, a buddy cop/action movie parody; Machete, an exploitation B-movie expansion of a faux trailer; and Vampires Suck, a thematically inconsistent spoof of everything and anything that's topical and popular.

We've reached a point where the film medium is being used less and less to communicate stories and ideas about the outside world than it is to relate stories and ideas back to the medium itself.

This isn't an entirely new development, either. Movies like this have been cropping up since at least as far back as the '40s, such as with Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, and as genres have continued to evolve, so too have parodies of film continued to grow more numerous. This became especially true during the '70s and '80s, when Mel Brooks and David Zucker hit the film scene.

More recently though, meta films have started to operate free from their more overt context, beyond simply being "spoofs". The need to pay tribute to what's come before has, over time, embedded itself in the subtexts of our media, to the point that deliberate unoriginality has now become the latest progression of filmic storytelling. And more than that, it's celebrated.

An early example that comes to mind is the character of Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark, who George Lucas created as an homage to action heroes of late '30s/early '40s film serials.

It's interesting to look at how things have changed since Raiders. Despite the film's protagonist being directly inspired by film serials, there was never a point where that inspiration turned to self-parody or wink-at-the-camera homage. Fast forward to the release of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull nearly 30 years later though, and that's precisely what the franchise became (see: Indy donning the fedora, the quick sand scene, Indy snatching the fedora from Mutt, etc.). The movie was practically a tribute to itself, in effect celebrating an idolized character who was already a celebration of other idolized characters.

This sort of meta filmmaking will reach an apex next year, when J.J. Abrams and Steven Spielberg collaborate on the film Super 8, which is intended to be an homage/tribute to Spielberg's 70's/80's Amblin films, like Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. I say again: Steven Spielberg is actively working on a tribute to himself.

As strange as this all is, it only makes sense that cinema would eventually venture to this point. Once the tropes and conventions of a particular genre/subgenre have been established, all that's left to do is recycle them. This has been true throughout the history of cinema, whether you're looking at the Golden Age of Hollywood during the late '20s-'50s, spaghetti westerns in the mid-'60s, exploitation films in the '60s-'70s, or even more recently, at the popularization of superhero/comic book franchises, video game movies, J-horror remakes, and "torture porn" horror flicks. All it takes is one or two notably successful films from these genres to generate public interest and mark out its territory, and the studios will follow suit with as many replicas as audiences are willing to consume. By the time audiences grow wary of the subgenre, it's often already progressed into parody, followed then by dormancy.

So what happens when there are no more genres left? What happens when one of the last remaining untapped markets is board game movies, and just about all viable options for originality have been expended?

In an age where we've already seen every formula that there is to see, all that's left to do is repeat and reflect on what's come before.

Is this such a bad thing though?

I suppose that's dependent on who you are. Mainstream viewers generally don't care about cinematic self-reflection, unless the film is clearly marketed as a "spoof" and features a heavy dose of bodily injury. This past month has been proof of that. Really, the only way for meta films to successfully reach a mass audience is for them to be played completely straight, allowing those without any meaningful investment in the medium to appreciate the film as simply another entry in a familiar genre. Inception is an example of this, as it managed to be a meta film without most people even knowing, and it's been greatly rewarded at the box office because of it. Would the film have found nearly the same success had its themes about filmmaking been made more readily apparent to casual moviegoers? I doubt it.

However, for those of us with a clear understanding of the storytelling rules and formulas that have embedded themselves in the medium, there's something kind of wonderful about watching these movies develop over time. We've been given the rare privilege of experiencing a major turning point in cinema, in a way that speaks directly to us.

To some degree, self-awareness in film has almost become a necessity, since anybody who's spent a significant portion of their lives watching movies and TV shows has already grown tired of the stories that most of them are telling. This isn't because the stories are bad per se, but because it's hard to engage in a story when you can predict every move its going to make before it happens. Meta films don't suffer from this problem. When you have films and shows that know they're formulaic, and slyly embrace it, it's easier for movie fans to maintain a personal connection with that material, specifically because of their familiarity with it.

It's no wonder that Evil Dead II and An American Werewolf in London have inherited such a passionate cult following. They were two of the earliest films to fit this mold, injecting a knowing comedic undertone into what could otherwise be seen as fairly serious horror tales. Scream did the same thing a decade later, albeit much more blatantly.

And with the advent of the '90s, we have now started to see the arrival of writers and directors whose entire bodies of work are defined by this recent trend, and many of them are arguably some of the strongest filmmakers working today. Four that come immediately to mind are Quentin Tarantino, Edgar Wright and Trey Parker & Matt Stone.

In the case of Tarantino, each of his films is like a beautifully crafted love letter to a specific genre/set of genres, which he uses as the bases for his own warped storytelling sensibilities. With Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino took his mash-up artist approach to another level, making a movie that was literally about the power of cinema.

It's also interesting to see how Tarantino operates differently than another meta filmmaker like Robert Rodriguez, his pal and frequent collaborator. Even though they each supplied equal halves to a '70s exploitation-style whole with Grindhouse, their results demonstrated how differently they processed those past inspirations to create films that felt uniquely their own: Rodriguez delivered an absurdly fun, goofy, over-the-top homage, while Tarantino offered up his own rendition of a true grindhouse flick.

Wright and Parker & Stone, meanwhile, were three of the first to bring the meta film angle to television, as they did with Spaced and South Park, respectively. (Later on we saw something similar with The Venture Bros., which most predominantly pays homage to the Hanna-Barbera cartoons of the '60s/'70s.)

Both camps soon went on to apply their satirist slant to film. Wright set his sights on zombie movies with Shaun of the Dead, cop movies with Hot Fuzz, and just about every movie genre ever with Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (which satirizes a culture that's become heavily defined by its filmic influences, among other things), and although Parker & Stone haven't been nearly as prolific as Wright, their marionette comedy Team America: World Police parodied big-budget action films with cunning accuracy.

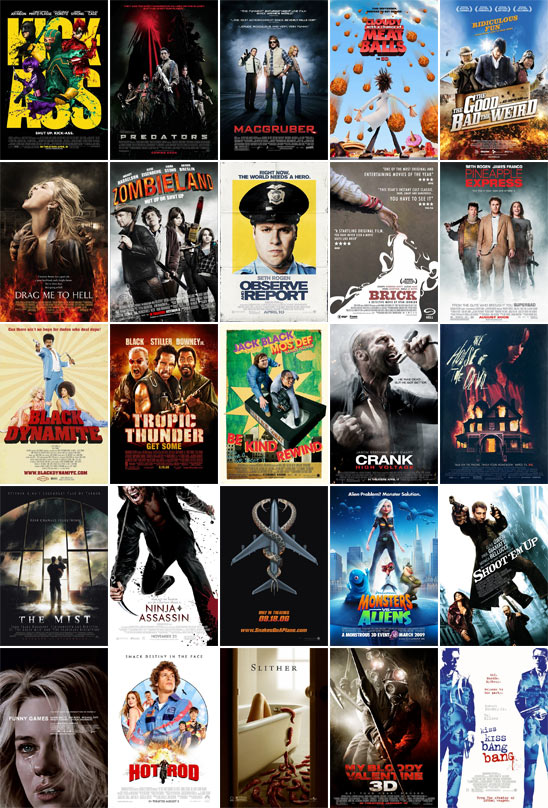

Lest you think the list ends there, here's a small sampling of other meta films, all of which were released within the past 5 years.

If films can be taken as a reflection of the culture we live in, today's films reflect a culture that's been utterly consumed by the media that surrounds us.

It was an expected development, really. As technology evolves, so too does our ability to stay in tune with the culture around us. Access to VHS and premium cable helped bring about this change, and with the introduction of the internet in our lives—which has resulted in an overwhelmingly immediate cultural connectivity that has drastically altered the way we consume media (e.g., remakes and reboots now come 5 years after the last film, not 30)—this evolution in film is only going to grow more pronounced. Just as the directors of today were inspired by the beloved subgenres of their childhood, the directors of tomorrow will be the kids who were inspired by the beloved satires of today.

What that movie landscape will look like, I have no idea. There's only so long that meta films can thrive before they go the way of the genres that preceded them and grow tired and stale—but until then, I'm going to raise a middle finger to the overly-manufactured studio crap being shoveled down our throats, and continue to enjoy, appreciate and support them.

Special thanks to Peter Sciretta and Dan Trachtenberg (from The Totally Rad Show).