Pete Docter Explains The Journey To Understand Sadness In 'Inside Out'

Filmmaking often comes down to one thing: guiding the audience. What do we see, and when, and why? With Pixar, which has the power to create all its images from nothing, there's always a process of guiding the audience eye to settle on one particular part of the image, no matter how many appealing details may color the margins.

That image control is part of storytelling guidance, too, and often a cover for the real heart of the matter. Pixar's films use big concepts — toys that have their own lives we never see, a rat who loves to cook, an adventure in a flying house — as a portal to concepts that are much more difficult to capture in a single image or marketing push.

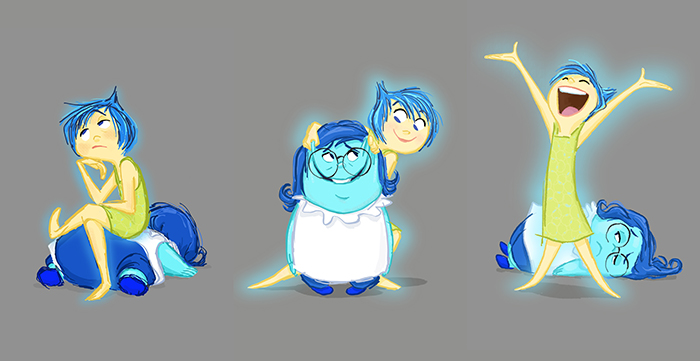

Inside Out has had a very specifically guided path. We know the film is about the five emotions, Joy, Anger, Sadness, Disgust, and Fear, who guide the responses a young girl named Riley has to her changing world. We know Joy is in the lead, but trailers for the film already show us that the core of the movie has Joy and Sadness literally going to the center of their own world — Riley's mind — on a journey of discovery.

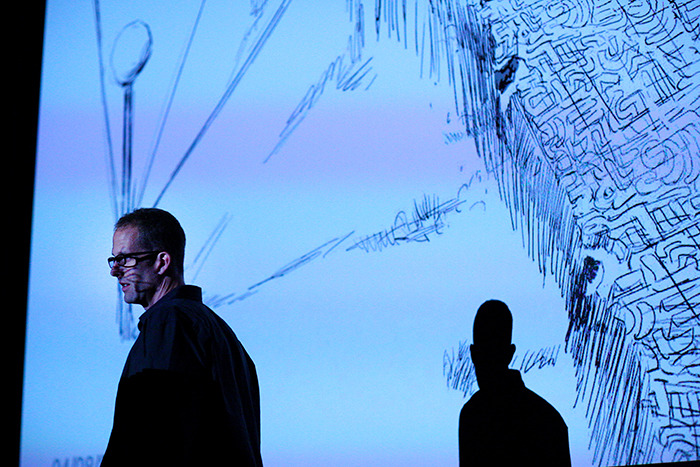

Six weeks ago I went up to Pixar's campus in Emeryville, CA, to join a few other editors to sit in on sessions with department heads who worked on Inside Out. Our last session was with director Pete Docter and producer Jonas Rivera. The pair discussed the creation of the film, but

Note: Prior to this interview, Pixar screened the first hour of the film for those attending — essentially the first two acts. So there are no true spoilers here, because I hadn't seen the end of the film. Anything that comes close to spoiler territory has been marked as such.We've heard about the advances made on the technological front here at Pixar, and in some ways, it sounds like you're getting closer and closer to the mechanics of live-action filmmaking.

Pete Docter: I think as a medium we're in this really sweet spot between the rich tradition of hand drawn animation and art, but also the cinematography and staging and all the things of live action. Because as you saw it's like a set, like a dollhouse. Even back on Toy Story we realized we could have that camera go up the character's nose and fly around. We said "let's just limit it to the grammar that we all know from watching films our whole lives." So two shots, wides, we speak the same language and think the same as you would on a live-action set. We try to use that grammar to further the storytelling so that you have the behavior of the camera and the composition is telling you things about the character and the emotional place they're at and all that kind of stuff.

Jonas Rivera: As our movies and our mediums evolve from Toy Story on, it's like our medium does lean towards realism with lights and shadows and virtual space, as far as the camera is concerned it's real.

When you're creating a film like this, does the world building come first, or is the story the first thing?

Pete Docter: It was a cyclical thing for us on this. It took us maybe two years to realize the interior design of the mind reflected what was at stake in the outside world. And that is: Riley's personality. So the only thing the emotions can effect are the inside world. They can't like make her do something. So if we get her in some sort of physical danger they're kind of out of the story. So we needed the interior world to reflect what's going on in Riley as a character. So that then meant that as we redid the story the entire world would change multiple times to the point where production was telling us we've got to lock this in because you'd change one thing and [sets would change, or go away].

Jonas Rivera: In the perfect production world, to continue the live action analogy, we'd build the sound stage and then we'd come in and shoot the movie. But as this movie is being developed, it's constantly changing. And even after we said "okay done, this is our set," huge things would happen. We'd have to exercise [that new idea] and see how it worked, but it was really, more than any movie I've been on before here, a cyclical thing.

You based this film in part on your own daughter's growth; did you consult with her?

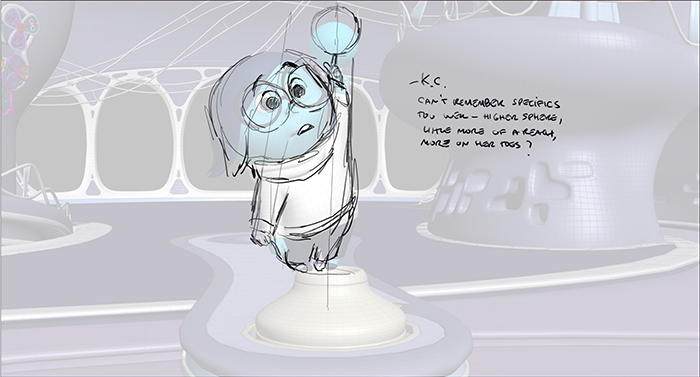

Pete Docter: Well the way it kind of worked I would just kind of like observe her as opposed to really engage her. Because I don't know that even she knew kind of what was going on in there. I know I didn't at that age, you know, you're just kind of experiencing it and things happen to you it almost feels. In fact that's one of the big things of growing up I think is realizing I have some ownership of this. I'm feeling angry, that doesn't mean I have to act on it. So it really came more from observation. A lot of the science study and research we did was helpful, not so much in the layout of the world. The Personality islands, things like core memories, we just kind of made that stuff to support the story. There are other elements like even weird things, like it's at night that the short-term memories are rerouted into long-term. That was something we read somewhere. That sparked this whole idea of this cool like kinetic ball sculpture, you know, they all go down once she goes to sleep. So there's a lot of stuff that was based on research, some stuff that was based on observation and some stuff we just made up.

Can you talk about the fact that, while Joy guides Riley, the mom seems to be guided by Sadness? (And the father is guided by Anger.)

Can you talk about the fact that, while Joy guides Riley, the mom seems to be guided by Sadness? (And the father is guided by Anger.)

[very slight possible spoilers follow in this paragraph]

Pete Docter: We wanted to make a straight point for Joy that her time is limited. This was stronger in an earlier version when that scene was first written. That Joy is looking down the barrel of [realizing] she's only going to be running things for a small amount of time. She's like "I'm not going to let that happen." So we wanted to kind of really showcase that to the audience as well, that Joy is not running the dad or mom, it's one of these other characters. We weren't trying to say anything sort of blanket about men or women at all, it was just... you have a temperament – everybody has a temperament. Though they might be happy [for a while] they'll go back to being sort of sullen, to their general sullen temperament. Or angry. I mean Louis Black, man, he would – we would be recording and he would kind of get tired and then he would go on a rant about the megamall in Minnesota and he'd be like [ANGRY SOUNDS] Alright, I'm back! It was almost a healing, relaxing thing for him to be angry. He enjoyed it.

There's also a balance, with the two parents work together and complement each other.

Pete Docter: That was based on just the way we feel about ourselves. It does seem like, as kids, you're like more Wild West-style, and more pure [in your emotions]. And as adults there's nuance, kind of complex things and there's more of that to come in the later part of the film.

Jonas Rivera: Yeah. Everything as a kid is almost an emergency. The food's coming in like everything is TEN. By the time you're older it's coffee, it's "eh, whatever..."

Pete Docter: I was just going to mention, too, that it was really a gag thing to have them all wearing mustaches or the glasses just so we would recognize who they are and what they are. But that also kind of seems truthful that at the beginning you're really wild all over the map and then you become kind of more a single person.

Jonas Rivera: You calcify into who you are.

You have a very collaborative workplace here, with people who are incredibly smart. Do you feel like you have to be the smartest people in the room?

Jonas Rivera: First of all, Pete, I want to hear your answer, but we never even attempt to try to be the smartest people, because you're working with all these computer scientists and artists. You can't out-talk [production designer] Ralph Eggleston about movies or animation. Everyone is going to know more than we do. Pete does a great job of not telling the lighting technicians how to do something, or what to do, but why he's after something. I've observed him doing that, which I think is really effective, the technical people step up to that.

Pete Docter: I think that's a good key to leadership that we both do is to not try to have all the answers ourselves but to recognize who will and when to bring whoever it is in. It's almost like a casting thing of like, you know if we got this person and that person I bet we could solve this pretty quick.

You seem drawn to emotional complexity in stories.

Pete Docter: I think it's just kind of a gut thing. I haven't really analyzed it, but I know the things that even as I look at other films that I love they're usually not films with tons of explosions and special effects, they're just simple films with great relationships. Like Paper Moon, I *love* Paper Moon. It's just one of the best films. Or The Station Agent. Films where kind of nothing really happens but you watch these characters grow and change and affect each other in deep ways and that's meaningful, I think, to me. If a film with lots of explosions have that then I'm in, but if it doesn't I'm kind of like eh... – I think it has to have some sort of relationship in there and emotional complexity.

For this movie I felt like the concept from the get-go was intriguing because of two things. One, the emotions as characters I was like, "this is right what we do in animation. We can write for these guys in ways that we could never get away with in live action." And then the world that we were going into I was like "oh my gosh if we can go see the train of thought and watch brainwashing" and some of these things that didn't end up in the film, I'm in just for the sort of high concept of it. And then, of course, the next step was developing a deeper bed of what is it we're talking about here, what is this movie really about? And that comes slowly over the course of four years.

Jonas Rivera: I think it's also how we think about animation, too. Paper Moon and those movies that we love and you mentioned a bunch, but we also love this medium and respect.. I don't know if "respect" is the right word, because it implies that others don't. Strangely, before going to film school the two films I saw that launched me into this were Pulp Fiction and The Little Mermaid. And I almost don't even think of them that much different. In fact I kind of thought if you put those two in a blender you'd get Pixar. But they're just movies to us. They happen to be animated and they have dramatic elements and things you'd see in these movies with families and we love that.

When you spend a couple years doing this do you find yourself evolving in different relationship to your own emotions or sense of emotional maturity?

When you spend a couple years doing this do you find yourself evolving in different relationship to your own emotions or sense of emotional maturity?

Pete Docter: Yeah it does. It really does. You're right. You start to kind of think of "okay why did that person actually do this? They say they're doing it for this reason, but what is it actually that's driving them and they're probably unaware of it" because a lot of us are. There's so many different layers to things that as soon as you become aware of something there's yet another one below it. So it's definitely changed the way I look at people behaving, people's behavior, my interactions with them. I think I'm a little – I grew up in Minnesota where, like, the model is everybody's nice and everything's pleasant and you don't say anything bad or negative, not that I'm looking for any negativity but I'm less sort of scared of some negative stuff happening. Like if we get mad at each other that used to really kind of freak me out. But now I recognize well that's healthy. It is what we do and it's everybody defending their own sense of what's fair and so on and so it's really been helpful for me.

Jonas Rivera: And my sort of hook into it is I'm a nostalgist, I love things from the past. And I've always felt like I could I'd go back in time. There's something about this movie and about memories and honoring that. But you know, facing the fact that you can't always be eight years old. There's something about going through the process of this movie that's helped that. Again, we don't want to sound preachy at all, too message-y, but just going through it and spending that much time and literally just the time. I mean Melissa my assistant like there's a picture of her in front of one of these calendars and Pete holding the first calendar we made of the film and she's pregnant and I have a picture of her, she did the voice for Joy, the scratch voice, and her holding her four-year-old daughter's hand in front of the mic, of my God our lives had like – we had spent a huge part of our life on this thing.

[very slight possible spoilers follow in the rest of the conversation]

While Joy is the lead character, certainly in the first act, the film seems to really be about Joy and Sadness, and learning about who Sadness really is.

Pete Docter: To me, that's the meat of it. That's the juice. The first story session, we came up with that sort of theme, which I won't get into because it'll give some stuff away. And we set out to make that and it really – we struggled with it. And it wasn't until the third screening in that we figured out the right way to unlock that message, but we knew that it was going to be important for the story from pretty much the beginning.

Jonas Rivera: We even tried pairing Joy up with someone like Fear, like what was the right kind of key emotion as you go through junior high? Coming back to Sadness felt a little more truthful.

Pete Docter: Because I think ultimately it's something that we can all relate to. We all want happiness in our life. I mean there are so many books on like how to be happy and what you need for happiness and you want that for your kid too, you want your kid to be happy. We literally tell our kids don't be sad,

Jonas Rivera – we command them!

Pete Docter: And yet there is a real value to all the other emotions that is part of the richness of life and it's not until you really recognize that I think you really have the ability to connect with the world in a deeper way.

Jonas Rivera: For me that was the simplified bullet point of what came out of all the research was just the simple fact that they have jobs, the reason you have each one. If you buy that, they're all trying to do a good job and they're all kind of a little bit competitive, and they all secretly think they know what's best, including Joy.... I loved the thing in the research, with Disgust, because Disgust felt a little abstract, she was a little harder to pinpoint. But no, there's a physical reason, all the way back to Darwin, of that face that prevents you from being poisoned. You eat something, a baby will spit it out, and then that translates into, when you're older, Disgust prevents you from being poisoned socially. So you don't miss some social cue, and you go into, like I did, into the eighth-grade with my Star Wars men ready to play and guys are going "you still play with those?" I got teased, like, "shit, I missed that social cue!" And so that was fascinating to think that's a job, that's an important job, and they're all going to work really hard to do their job.

Pete Docter: And with Sadness specifically, in America you read about people medicating to avoid sadness. They don't want to experience Sadness and yet it's such a vital part of being human.

Jonas Rivera: Yeah. Physical pain – like I read this thing where a baseball player couldn't swing the bat so he got cortizone shots in his elbow and he can swing the bat. The sports doctor was like well you still feel the pain, or the pain is still there but you can't feel it. Like there's a reason why you can't swing the bat.

Pete Docter: It's your body telling you relax.

Jonas Rivera: So now he's approaching it sort of like how we treat Sadness.

***

Inside Out opens on June 19.