'Godzilla: Planet Of The Monsters' Review: What You Need To Know About Netflix's CG Anime Film

Hollywood's next live-action Godzilla movie is scheduled to hit theaters in 2019, just a few months before its title character turns 65 — an age traditionally associated with retirement for a lot of us frail human beings. This film is the sequel to Gareth Edwards' 2014 Godzilla reboot, which hit theaters a few months before the character turned 60, the age when AMC moviegoers start collecting senior citizen discounts.

While he may be getting a little long in the tooth by human standards, to write the king of the kaiju off as geriatric would be to ignore his prodigious lifespan. In Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters, the 30th Toho production and first-ever animated feature based on Japan's greatest pop cultural export, that lifespan is established to be at least 20,000 years. As we reported last month, the film is coming to Netflix in 2018 as part of a slate of 12 original anime series that the streaming service plans to release over the course of the year. It already had its opening weekend in Japan, however, and I saw it at Toho Cinemas Shinjuku, a landmark Tokyo movie theater housed in a building topped with a life-size Godzilla head.

So let's take a deep dive. Here's what you should know about Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters before you stream it next year.

The Film's Title is an Intentional Sci-Fi Homage

If that title, Planet of the Monsters (Kaiju Wakusei in Japanese), sounds like an homage to Planet of the Apes (Saru no Wakusei in Japanese), that is probably no coincidence, as the movie's plot is indeed something of a riff on Planet of the Apes.

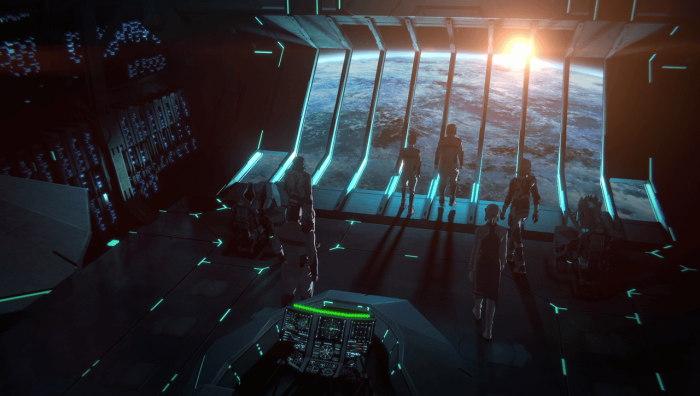

A ship full of human refugees drifts through space, having evacuated Earth after the planet was, as the movie's website puts it, beset by "the emergence of colossal creatures" near the end of the twentieth century. During the film's opening credits, these creatures are shown devastating major cities like New York, London, and Paris. Aided by the so-called "Exiles," a group of humanoid extra-terrestrials reminiscent of the Elves in Lord of the Rings, the refugee ship has traveled for two decades, across a dozen lightyears.

When it turns out the planet they were bound for is uninhabitable, the humans must soon make a return trip to Earth. One of them is a young man named Haruo, who as a boy, witnessed the death of his parents during an attack by Godzilla on the spaceship launch site. For Haruo, it was only 20 years ago when that happened; but if you saw Christopher Nolan's Interstellar, you may remember that the effects of time dilation in space can seriously skew temporal numbers.

20,000 years have elapsed back on Earth, more than enough time for Godzilla and other monsters who look like rock pterodactyls to exercise full dominion over the planet. While there is nothing equivalent to the iconic beach scene with the Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes, there is a fun little Easter egg on a map teasing how buildings in Tokyo's famous Shibuya district have become fossilized.

Let's talk, now, about the second thing you should know. This one requires a little more discussion, and it could prove contentious.

The Film Continues the Tradition of Withholding Sight of the Monster

If you are one of the people who was disappointed by the lack of screen time for Godzilla in the 2014 movie bearing his name, then you should know that Planet of the Monsters involves a lot of talky setup among human and humanoid characters in scuffed-up spacesuits. Roughly the first half (maybe the first two-thirds?) of the film plays out in this fashion.

It is unclear, at this point, whether Netflix intends to release the film solely in English-dubbed form or whether there will also be an English-subtitled version available that maintains the beauty of the spoken Japanese. In the U.S. iTunes Store, for instance, there have been times when films like Ghost in the Shell and The Boy and the Beast were only available in dubbed form.

Personally, I have never been a fan of dubbed anime. With the exception of some of the Studio Ghibli films that Disney has (or had, until recently) distributed in the U.S., I think the voices in dubbed versions tend to be over-exaggerated. I do not mind reading subtitles, but I can see how that might detract from the visuals and be a real turn-off for some people, particularly in a dialogue-heavy film like this.

Last year, in his Fantastic Fest review of Shin Godzilla, Jacob Hall wrote about how that film, otherwise known as Godzilla: Resurgence, strove in part to be a political satire. Co-directed by Hideaki Anno, the creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion (it even utilized some of the music from that epic anime series) Shin Godzilla also chose to skimp on the title monster, preferring instead to show us scenes of ineffectual government officials conferring at length, only for them to reach the monumental decision that it was time to move to another room (all while Godzilla continued to wreak havoc on civilization outside). Planet of the Monsters lacks that element of political satire, yet it does call to mind Evangelion with its abundant use of technical jargon and holographic control-room displays.

Maybe it is just the fact that apes are innately more humanlike, capable of showing emotion with their faces, but compared to, say, the Andy Serkis' King Kong, Godzilla has never struck me as a monster who conveyed much interior life. Here again, he does not display personality so much as he exists as a force of nature. In the background, that force of nature rampages unchecked, while in the foreground, minuscule humans show themselves capable of great courage and dispiriting weakness as they struggle to survive in the face of overwhelming adversity.

For some fans, this might situate Planet of the Monsters firmly in the pantheon of strong franchise entries that capture the heart and soul of what Godzilla is truly about. But that asks another question: what is the true Godzilla ethos? At its core, is Godzilla meant to be a disaster movie, a monster movie, or some singular permutation of both?

As someone who moved to Tokyo just in time to witness the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami unfold, and who experienced firsthand the swaying buildings, the rolling blackouts, the radiation fears, and people's panicked runs on the supermarket for emergency supplies, I can appreciate how a film like the aforementioned Shin Godzilla might be seen as a socially relevant disaster metaphor. One of the more memorable bits of news imagery from the crisis back in 2011 was helicopter video of a boat spinning toward the center of a giant whirlpool in the ocean. It looked like a toy boat spinning toward the drain in the bathtub. It looked like something out of a Godzilla movie.

With the way Japan is enveloped by the Ring of Fire — all its tectonic activity, the fact that it holds over a hundred volcanoes, half of them active, not to mention the constant seasonal danger of typhoons — there certainly is a real-world precedent for a story about people persevering bravely while under the specter of looming disaster at all times. To say nothing of Japan's history as the only country to have come under nuclear attack.

Before it was re-edited and Americanized with the silly insertion of Raymond Burr, the actor who played Perry Mason on television, the original 1954 Japanese version of Godzilla, a.k.a. Gojira, delivered a dose of the morose. In one shot, as Godzilla destroys Tokyo landmarks like the Kachidoki Bridge, and smoke rises off the burning city into the night, a mother is shown huddling in the corner with her children, telling them they will be with their father soon in heaven.

Scenes like these were heavily informed by the wartime firebombing of Tokyo and the subsequent atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, along with more contemporaneous historical incidents like that of the 1954 Castle Bravo nuclear detonation. Even today, in a place not far from Tokyo Disney Resort, you can visit an exhibition hall where the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, or Lucky Dragon No. 5 — the tuna boat whose fishermen were irradiated by that detonation — rests on permanent display.

After Godzilla Raids Again, Toho's 1956 sequel, the franchise began to move away from its darker roots, into the realm of fun, castle-smashing suitmation. In the same way that Terminator 2 changed Arnold Schwarzenegger's T-100 from an unstoppable killing machine into a smart-alecky teen's new best friend, Godzilla would eventually be depicted less as the central antagonist and more as an unlikely defender against other kaiju. Over time, a new spirit formed whereby Godzilla became a friendly kids monster. Plenty of children in suburban America, myself included, were left to play with Godzilla toys without being the slightest bit aware of Hiroshima and Nagasaki until much later in history class at school.

Though its title would seem to invoke this B-movie image, Planet of the Monsters fits squarely into the recent trend of taking the Godzilla franchise back to its roots. If Gareth Edwards restored the somber tone, and Hideaki Anno restored the simple humans vs. Godzilla nature of the story, then Planet of the Monsters honors the steps they took.

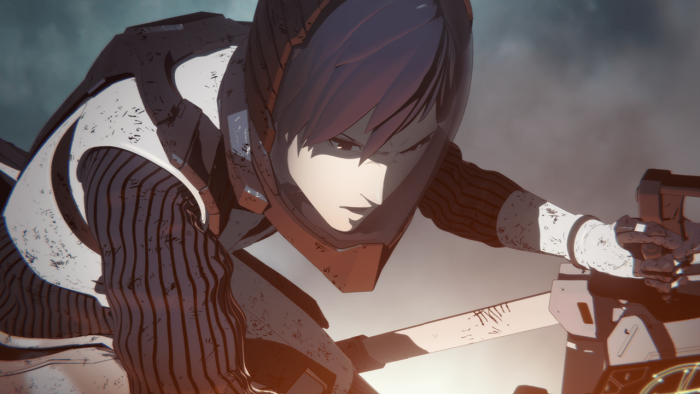

By now, it almost seems trite with a movie like this to make the usual Jaws or Alien comparison. But for the better part of Planet of the Monsters' running time, Godzilla is once again portrayed largely as an off-screen threat, one whose every shuddering step seems to hammer home the scale of an impending cataclysm that humans have in some sense brought on themselves. Aside from a couple short glimpses of him in flashbacks at the beginning, it is only toward the end of the movie that Godzilla himself actually shows up on-screen as a lumbering menace, looking more rocky than scaly in hide. Even when his CGI bulk does appear and Haruo and company start flying around on hover-bikes to fight him, there is a curious lack of any real money shot to establish the king of monsters. When at last we are allowed to luxuriate in a close-up on his face, it almost seems like an afterthought. Rather like the concept of plot resolution in this movie.

Which brings us to final thing you should know.

The Film Doesn’t Work as a Standalone Movie

If you would like to avoid even a hint of spoilers and go into Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters without any more pre-conceptions, then you might want to bow out now, as we are about to discuss the film's ending in a way that will steer clear of specific plot points but still try to offer some general criticism about what is sure to be a frustrating aspect of the viewing experience for some people.

Over the weekend, as Planet of the Monsters stormed screens in Japan, we wrote about how it is only the first installment in a planned trilogy. A second and third animated Godzilla film have already been announced.

Without delving into details about what exactly happens in the third act, it is enough to say that the film is completely open-ended. There is not any kind of satisfying resolution to the plot, and in fact, the last scene leaves the viewer hanging about as badly as the "To Be Continued" at the end of Back to the Future Part II did. Whereas that was the direct sequel to a beloved movie, however, Planet of the Monsters can only rest on the goodwill that other Godzilla films not connected to it have engendered.

This might be an alarming comparison, but as a cinematic experience, it reminded me of what I heard about The Devil Inside, the found footage horror film that notoriously ended with a link to a website where the "ongoing investigation" would continue. In the same way, Planet of the Monsters ends very abruptly, then there is a post-credits scene teasing something random and new for the next movie. The last image that appeared on screen before the lights went up in the theater was literally an advertising still for the release of Godzilla Kessen Kido Zoshoku Toshi (Godzilla: Battle Mobile Breeding City) in May of 2018. Exiting into the theater lobby, a person might now notice the words "Coming Soon" juxtaposed with "Now Showing," as posters for this next movie stood out in a side-by-side display with Planet of the Monsters posters.

For better or for worse, this is the Iron Man 2 of Godzilla flicks. Only, in this case, the sense of it being a commercial for the next movie is greatly amplified by that open ending.

Maybe it's a sign of the times for the motion picture industry. After all, with the developing Monsterverse from Legendary Pictures, Godzilla has already entered the shared-universe fray. Why not go full Marvel and serialize his adventures?

The only problem with that is, unlike the first Kill Bill, which also ended on a total cliffhanger, Planet of the Monsters is not being marketed with a Vol. 1 tag. Again, it was not until the film's opening weekend here in Japan that news of its forthcoming sequels suddenly surfaced. It is one of those things where, as the movie's closing credits began to roll, I turned to the person next to me, stupefied, mildly infuriated, seeking another pair of eyes to anchor my extreme "WTF" stress.

On the one hand, leaving the audience to grapple with a cliffhanger might make Planet of the Monsters ideally suited to the Netflix format, where subscribers can just wait and binge-watch the whole animated Godzilla trilogy after the other two films have hit the streaming platform. On the other hand, with no immediate payoff, and the release of these films being staggered over a period of six months, it might be a lot to expect casual viewers to stick with the story that long.

Again, this might be an alarming comparison, but as someone who recently stopped watching The Walking Dead after seven seasons, the conclusion of this film reminded me of the Season 6 finale of that show, which infamously introduced the character of Negan with a big tease that left some important things up in the air until the next year.

In the final analysis, it is probably better to think of Godzilla: Planet of the Monsters less as a movie and more as the first episode of a TV mini-series. You can either roll with that or not. In my own case, I was sufficiently intrigued by the setup and elegant animation that I am willing to fight back any lingering resentment about having forked over train fare and ticket money to see a film with a non-ending.

Besides, whatever reservations I might have, Godzilla's stock is on the rise. Over the last few years, other life-size Godzilla installations have popped up around Tokyo, giving the king of monsters increased visibility in his home country's capital. Two years from now, when the live-action King of the Monsters releases theatrically, followed by Godzilla vs. Kong in 2020, we may all be able to look back on Planet of the Monsters as the start of a colorful new chapter of stateside visibility in the Godzilla franchise's long and venerable history.

Until then, if you are a huge anime and/or Godzilla fan, and you do not mind some significant loose ends between episodes, then you can probably watch Vol. 1 of this series and enjoy it for what it is. Other interested parties would be advised to just wait and watch the whole three-part series when it is available on Netflix.