'Mad Max: Fury Road' - Eight Awesome Facts About The Making Of The Film

Mad Max: Fury Road was over a decade in the making, and hit the screen with a rich backstory. While it's more fun to let the characters on screen exist with only the information we're given in the movie, the tales of the creation of Fury Road are so good that we have to dive in.

Below we've got eight of our favorite bits of Mad Max: Fury Road trivia, from the insane planning that went into the stunts, to the freedom that digital cinematography allowed in collecting the insane amount of footage that makes up this movie and the fact that the Mad Max: Fury Road blu-ray will feature a black and white version of the film with an isolated score as the only soundtrack.

We have a few sources for this piece. The major one is the first screening of the film set up for critics in Los Angeles, which was followed by a discussion between George Miller and Edgar Wright. Any blockquotes from Miller below that are not explicitly sourced come from that Q&A.

There are also a few tidbits that Miller said to me directly when I spoke to him after that screening, specifically a bit about doing a black and white version of the film for blu. And then we've drawn info from around the internet, all of which is sourced specifically.

Over a Decade of Development

Here, in one paragraph, is the very brief history of Fury Road from the initial plan to shoot in 2001 to the release this year.

We started to kick this off in 2001, but it fell away. The American dollar collapsed with 9/11, the budget ballooned, we had to get on to Happy Feet because the digital facility was [ready]. Then it rose again, and we had unprecedented rains in the outback of Australia. Where there was red desert there were now flowers. We waited a year for it to dry out. It didn't, so we had to take everything from the east coast of Australia to the west coast of Africa, to Namibia where it never rains. We had to do it old school, this is not a CG movie, we don't defy the laws of physics, and so we had to stage it. For 120 days, and every day was a big stunt day.

Every Stunt Was Rigorously Planned and Tested

Miller has been working with some of the same crew members for decades, and one guy who was just a young man on The Road Warrior became an essential part of the Fury Road crew: Guy Norris.

And while the stunts in the film look like they are as in the moment as it's possible to be, in fact they are all the product of painstaking research and development. George Miller explains:

We had Guy Norris, who did second unit directing and principal stunt coordinating. He was a 21-year old on Road Warrior, and partly because of the delay in the weather we were able to rehearse all the stunts back in Australia. Every stunt you see we'd rig up an old wreck, get all the weights right. He's one of those who uses a lot of computers, goes through engineering and really tests it on the computer, and then tests it in reality.

So when that big war rig rolls at the end we not only had to pull that off safely, but we had to land it right on the spot with the cameras. So they rigged up something like that and were able to do it. it was very painstaking preparation and work.

The Freedom of Digital

The previous Mad Max films, as products of the '70s and '80s, were shot on film. But George Miller went digital for Fury Road. In my review I argue that the film has to be digital, and this is part of the reason.

George Miller:

You couldn't make this as a CG movie. Even if you did it really well, people wouldn't know it. Plus, [now, with digital film] you didn't have to wait for it—you pull off a stunt, check your cameras, and there you go.

Because of the digital cameras we shot — this is ridiculous — we shot 480 hours of footage. That's three weeks continuous, watching without sleep. With digital cameras you can just run them through. In the old days, with a high-speed camera, you'd burn up your celluloid in very quick time, here you can run it for 40 minutes at a time. [In the old days] for every explosion you had to get your crew out, the guy who started the camera, you've got to get them out. Here you just run the cameras, so there's a lot of wasted footage. It was dumped in the lap of Margaret Sixel, the editor, who happens to be my partner, who was back in Australia. We said "here." [mimes dumping a giant box] She had to find the two hours that made up THAT. [gestures back towards screen where Fury Road was just projected]

So what does that mean? It means that a crew could drive for miles and miles with cameras running trying to get one shot. Miller explains:

Guy Norris was chasing a shot which required sun to match it. It started to cloud over, and Guy had to get this shot. I was in the edge arm and I was listening to him squawking, and he said "I'm going to go inland to try to catch the sun. He went inland, and every so often I'd hear him as the squawking got more faint, and more faint. He traveled 25 miles inland in Namibia, and then I heard him yelling "yeah, we got it!" I call him "the man who chased the sun."

***

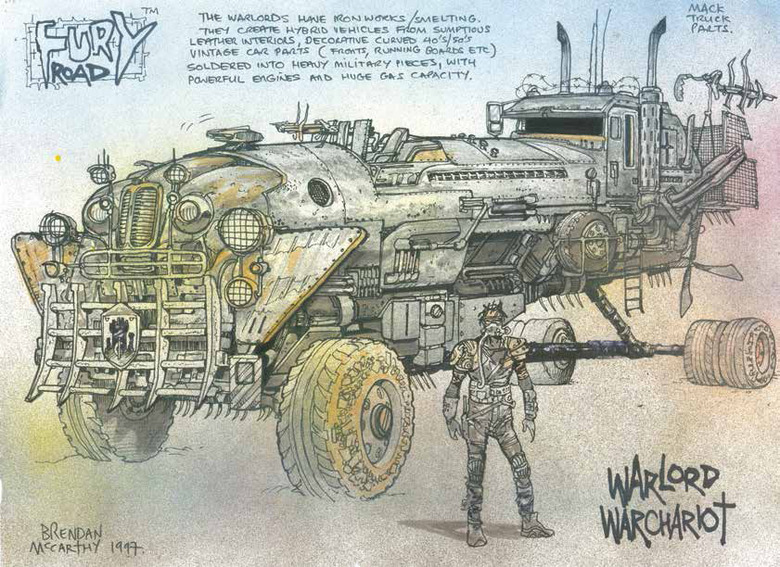

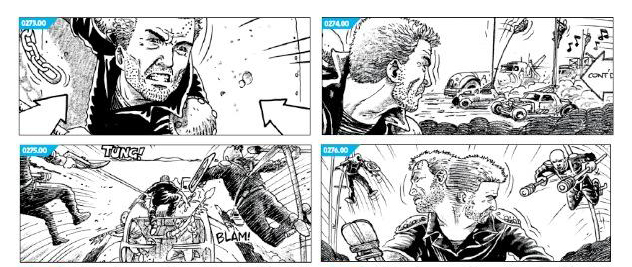

The Storyboards Were the Script

Fury Road was begun with a storyboard rather than a standard script, but these weren't just any storyboards. In addition to the extensive concept art created by Brendan McCarthy, whose input was so significant that he's got a co-writing credit, there were about 3500 drawings done by Mark Sexton and other artists. These cover basically every moment of the film.

George Miller:

I got in touch with Brendan McCarthy, a wonderful artist who had sent me some terrific drawings of Mad Max. I asked if he wanted to come down and work on it. We worked with Mark Sexton, Peter Pound, two other fine storyboard artists I'd worked with in the past. We sat in a room and basically laid out 3500 panels, which, so much of the movie is what you saw today. The big dimension that's missing is time, those rhythms you're finding in the performance and ultimately in the editing suite.

The storyboards were great, because you don't have to write direction or camera movement, you knew where you were. Even the cast had the storyboards, and knew where they were meant to be at any given moment. Those storyboards were a very useful tool, and people were able to build on that.

In an interview with io9, Charlize Theron talked about the relationship to the film's boards and script.

...there was a script; it just wasn't a conventional script, in the sense that we kind of know scripts with scene numbers. Initially it was just a storyboard, and we worked off that storyboard for almost three years. And then eventually, there was a kind of written version of the storyboard, which just felt like a written version of the storyboard, again not like a script. I think the hardest thing for us, as actors, to get our heads around, was that the movie really was one big scene.

Usually you have scenes and this was one big scene. So we shot one big scene for 138 days. That was tricky because everyday you show up and you don't really know where you are in that scene. George was really at understanding what he wanted. And the movie was in his head. After a while ,we all understood that we just had to let him do his thing.

The Vehicles Truly Are That Impressive

While there's a lot of information out there about the cars in the film, it's easier in some ways to see that they're real. Check out the test videos of the Bullet Farmer's ride in action. This thing is terrifying, and incredible.

Some of the Weirdest Stuff Was Done for Real

Miller was afraid the pole cats — the guys mounted high above the cars on swinging poles — would not be a practical on-set effect. But the production delay allowed enough development time that they figured out how to do it.

And the delay... those pole cats, I thought we'd never be able to get those really moving. I thought we'd shoot the guys up there, and we'd comp in the vehicles traveling through the landscape. And then gradually, bit by bit, they figured out how to do that. One day Guy [Norris] sent me some footage. I was in the middle of Happy Feet 2, and he was out in Broken Hill in the center of Australia. He sent me this footage and the guys were up there doing it! And there were several of them.

Olympic Feats of Safety

On a stunt movie like Fury Road, there's always the potential for injury or even death. That means that the safety of crew and performers alike has to be prioritized above all else.

Indeed, to make sure that everyone would be safe on this film, Miller & Co. went to the crew that did rigging work for the Olympic opening ceremonies.

The notion of hurting someone really badly was there. we were obsessed with safety, we had great, great riggers. We got the guys who do the Olympics, who did the Sydney and Beijing Olympics, who fly those people around. [They get] one take, for the Olympic opening ceremony, and they're really on top of their game. It got so we could use our real cast in so much of it.

***

Black and White

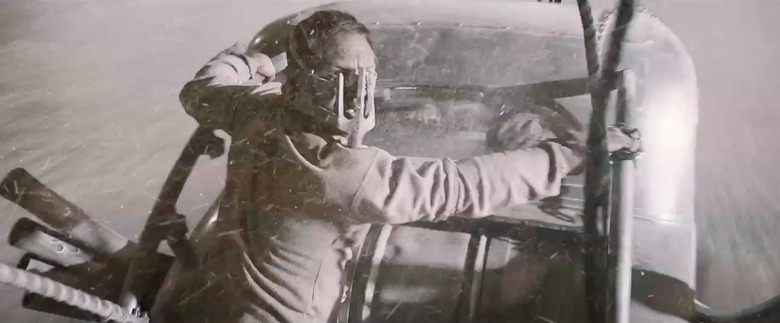

This is a big, explosive, colorful, loud movie. Indeed, there was a very definite plan behind making this film as colorful as possible:

We spent a lot of time in DI (digital intermediate), and we had a very fine colorist, Eric Whipp. One thing I've noticed is that the default position for everyone is to de-saturate post-apocalyptic movies. There's only two ways to go, make them black and white – the best version of this movie is black and white, but people reserve that for art movies now. The other version is to really go all-out on the color. The usual teal and orange thing? That's all the colors we had to work with. The desert's orange and the sky is teal, and we either could de-saturate it, or crank it up, to differentiate the movie. Plus, it can get really tiring watching this dull, de-saturated color, unless you go all the way out and make it black and white.

Note that comment in the middle, about the best version being black and white. There's a precedent for black and white in this series, but it's one only George Miller, Brian May, and a few other people would know.

The best version of Road Warrior was... they used to do a "slash dupe" in music. To make a really cheap print, they'd make a black and white version for the composer. They used to put lines [across it], if you see old documentary footage of composers in the past, you'd see them looking at the screen and conducting, that was a slash dupe, and it was black and white. And you'd mix the sound that way [too]. And every time I saw the black and white I thought "oh, my god!" It just reduces it to this really gutsy high-con black and white, very, very powerful.

George Miller's own film education comes back to the earliest language of black and white, and silent films. He explained,

I used to live near a drive-in that was on top of a hill. Often going home I wouldn't drive in, I'd park outside and watch the movies silent. And then I became obsessed with silent movies and realized that the basic syntax of film... Kevin Brownlow basically said that all film language is defined by the silent movies.

And, in fact, the old silent movie techniques lead to action filmmaking now, and an action film like Fury Road is the sort of thing that can only be a movie.

You're not slumming in action. You're trying to use a language that cannot exist in any other medium. You cannot do it in the theatre, you can't do it live.

Miller's editing techniques also call back to silent filmmaking. His preferred editing system includes working silently, to make sure that everything plays on a purely visual level. Miller told Margaret Sixel, who primarily cuts documentaries and had never cut an action movie, to rely on her doc instincts:

If you cut it like those [other modern] action movies where everything's really really fast and it's an excuse for not respecting space or geography, it's a kind of visual noise. You want the notes to be clear.

A while after this talk, during a post-film reception, I spoke with Miller about his affinity for that black and white version of Fury Road. He said that he has demanded a black and white version of Fury Road for the blu-ray, and that version of the film will feature an option to hear just the isolated score as the only soundtrack — the purest and most stripped-down version of Fury Road you can imagine.

Want to see how that version could look? My friend Renn Brown mocked up a quick black and white version of the trailer after reading this piece. Check it out:

Video Bonuses

Here's nearly 20 minutes of footage that shows Miller's favorite tool, the edge arm, a rig which allows the camera to be mounted way out away from the body of a vehicle, and manipulated via remote. (He says "it's like being in the middle of a video game.") That and many of the other tools of production used for the film are seen here:

And for when you have a lot of time, the video that follows is nearly two hours of conversation with Fury Road's cinematographer John Seale, who was coaxed out of retirement by George Miller to shoot this film when The Road Warrior and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome cinematographer Dean Semler had to drop out. Seale was 70 at the time, by the way, and Miller turned 70 just before this film's release. So think about that while you enjoy the fruit of their labors.

At the Q&A I attended, Miller said of Seale,

We had a really good camera crew, led by Johnny Seale. He's not intimidated by having multiple cameras, and so we had a really clear pattern. And he operates. He turned 70 on the movie, and he was on top of the war rig doing that stuff, he's a very fit sailor.