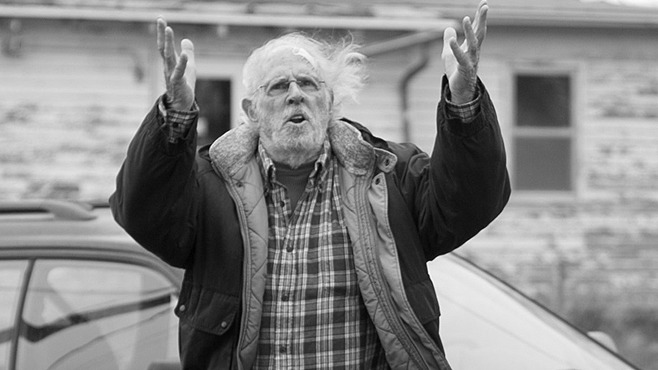

/Film Interview: 'Nebraska' Star Bruce Dern Explains The Challenges And Risks Of His Lead Performance

Bruce Dern has seen it all in Hollywood. His TV work in the early '60s positioned him to be right in the middle of the New Hollywood explosion that happened late in the decade. He's in a mind-boggling array of great films, from Hang 'Em High to They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, to The King of Marvin Gardens and The Driver — it's impossible to reel off a quick summation of his career without feeling like you've left out five essentials.

Or maybe Dern has seen almost all of Hollywood. Dominating as the heavy, he's never quite broken into lead status, and he's never won an Oscar. (He was nominated for Best Supporting Actor in 1979, an Oscar year thick with great performances, for his role in Hal Ashby's Coming Home. Christopher Walken won, for The Deer Hunter, even as Jon Voight and Jane Fonda won the Best Actor and Actress trophies for their own work in Coming Home.)

So Nebraska feels like a singular moment in Dern's career. He's directed in the film by Alexander Payne, one of the modern filmmakers who feels most creatively connected to the biggest years in Dern's career. He's got a lead role, and it's one which forces him to look past his own natural tendency to unleash a torrent of conversation. As scripted by Bob Nelson, his character, Woody Grant, barely talks at all. Even as we wonder about his mental capacity, he's fixed on a goal: claiming the million bucks a piece of junk mail tells him he's won. Dern approaches the work with quiet intensity and a real vulnerability, bouncing off co-star Will Forte's own uncharacteristic straight man role. The result is unlike anything else you'll see this year.

I spoke to Dern in Los Angeles, and we discussed acting challenges and risk-taking, Payne's quiet direction, and the goal of becoming a character, rather than simply performing as one. There's even some trivia about The Exorcist in here, for good measure.

I get the sense that you're a born raconteur.

I tell stories, yeah.

So I'm curious about you doing a role in which you speak very, very little.

Well, they challenged one of the ways that I play the role. The biggest challenge was to do exactly what I tell Will I'll do at the end of the movie, "I'll shut up." That's why I love that line so much, I loved that right at the very beginning, the detachment of the guy not really aware of what's going on around him, maybe. Maybe he's more aware than you think. People [like Woody] can't tell you and that's the charm of them and also the disability of them. So the biggest challenge was so be detached and to not be aware of what was going around and appear to have that be real.

The second challenge was not to show anybody the work of acting in the movie, and we all accomplished a lot of that. It looked like it's total moment to moment honest behavior all the way through. [Alexander] will be there with a camera and take the time to find that, so the audience can see the behavior evolving. That's really what I wanted to do with the role.

Alexander sounds like he's relatively low-key as a director; does he just nudge you here and there?

He'd be right there. He's right where you are. I mean he's not way back in the other room on a monitor or office or that or on his cell phone. He's there and he's excited to be there, because he's actually watching the movie. He knows the script works. He knows his crew knows how to do everything. They've been with him six pictures now and so he's just sitting there. Some times he'll look after a cut and you look at his face and he's like just a little kid. He just sits there and watches it and enjoys it. If he wants to do something more, he just asks "a little more, a little less." He's not going to tell you how to act. He hired you, because he knows you can act.

Is that ideal for you? Is that the director that you'd prefer?

I need direction probably more than anybody else, otherwise I will give a "performance" instead of being somebody. The difference is, in this movie, I tried not to give a performance. I tried to be a person.

How is one different from the other?

You just have to absorb the character so much, and become the character so much, and be with a director who allows you to have the time with the lens on you and all of the other people. You have to tell the story where the audience is really following the people and who they are, and the audience is not aware they are watching anything other than a documentary so to speak, and that's his style and it works. What happens is about five minutes into the movie you think "Well when are they going to bring on the actors? When are they going to do more than this, so we know it's bigger than life?" Your job is to be life like, not bigger than life.

Let the size of the screen do that.

I've said a hundred times now, when we first came to Hollywood, we got to work with the legends and they were bigger than life. They played bigger than life. [John] Wayne was a big, big man. Ms. [Bette] Davis was a small lady. [Robert] Mitchum was a big, big man. I mean those were the kind of people that I got to work with and they were just big folks.

Here we try not to use the screen as a tapestry, but as a slice of life. Then we're in the kitchen, we're in the dining room, or hotel room, or whatever it is and to just be as honest and real as you can.

Alexander gave us an opportunity to be able to do that and it's suicide [to try it], but he insists on it, because he only casts people that he thinks are those people. And then he says that's eighty percent of his job, the casting, and that was very refreshing to hear. Very nice. And if you're the guy who didn't get the role, well it ain't so nice. I've been the guy who didn't get the role of Woody for about fifty years. You know what I'm saying?

I had to work my way up and I guess I probably got to triple A when I was about forty-one and you keep getting worried "Well, am I going to get a chance before I'm so out of it that no one wants to cast me anymore?" And he gave me that chance. That's a big victory for all of the people connected with Nebraska. We got a chance to be in a movie that can be a good movie and that people may want to get out and see. That's what I'm doing here and what all of us have been doing, and what Alexander does to begin with.

Is there risk in this role for you?

Is there risk in this role for you?

Well the risk would have been to be less than what I hope I got to. I surely didn't get to the very top of what I wished I could do, but the risk is failing when you have a script this magnificent, failing to make the movie come alive, because it's not a movie that's juiced by music or pyrotechnics or genius or wizardry or anything like that. It's a movie about the people. I came to do movies about people. Alexander wants to make movies about people. The danger is, the trap, is to overact, to try and perform and make yourself not part of a family, but the star of a movie. Those are the traps. Those are the dangers. You don't ever want to do that and I'm sure I've been guilty of that down my career, but a lot of times you're guilty because you want to have the characters survive. If he's not the main character in the movie, then you've got to find something that makes him at least main for the time that he's there. So you start inventing stuff that doesn't belong and a lot of times... I mean that's where "Dernsie" came from. I've had other directors come up to me on big movies and say "You know what? It's not there. Give me a Dernsie. I need something."

It was basically our embroidery that just enlarges the on screen life of a character where you see a part of him that's not on the written page, or he's not a big enough character that the movie is following him all the way through. The one thing I've always demanded in roles and I haven't gotten — maybe about half the time only — is a beginning, a middle, and an end. "Where does he come from? Who is he while he's there? And where do other people think he's going?"

There's a lot of stuff about the background of this character that is all on screen, but articulated by characters other than you. Other people will say "this is who Woody is," but you don't have to do the exposition. Does that make the character feel more rich?

That's a fabulous question, possibly the best question I've had in all the time I've been out with the film, because what you're really saying, it seems to me that... I have always had to have roles where I do it for myself, where the character explains who he is, explains why he's whacked out in Black Sunday, even in Silent Run. Even in Marvin Gardens. In Coming Home, no one understands [my character's] viewpoint. In this movie they tell a viewpoint, so all I'm doing is just there as a character they are talking about. He has a pretty interesting backstory, but you might say "the guy's not interesting." Well who do we know in our lives that appears not to be real interesting, and then somebody tells you what they've been through and you say "Oh boy..."

Quentin [Tarantino] will be the first one, along with Alexander, who will tell you that movies are about what went before the movie started. That's the way I start with a character. "What would he do not just yesterday, but what's he done since he was seventy-six years old, since he was one, two, three... What happened in his life?" When you get that, then you learn about who the characters should be and then the third thing is to reverse the question of "Where does he think he's going?" No, where do other people think he's going? That immediately gives you a paranoia to the character.

So if I meet you, most people are interested in "Well who are you? What are you all about?" And no, I'm interested in "Who do you think I am?" Is that ego? I'm sure. Is that entitlement? No. But what it really is is a way to examine what's really going on, "Does he think I have game? Does he think I'm awake?" If you do that and everybody does that, then you get kind of what the guy who wrote the book on it a long time ago in the '60s called it, "stroking." Which is, I say "Hi." You say "Hi, how are you?" I say "I'm great, how are you?" So each time you do one more stroke than the first guy did and it ends up you're each doing paragraphs and then you're sitting down having a coke or you're doing something togeher. A guy wrote a whole book about it, it was called Stroking and that's what stroking is. [Note: I can't find a listing for this book; if you have it, let us know below.]

What vision of the Midwest and America in general does this movie have?

I think this is about as honest a look as what's out there today. I mean it's bleak. [When I was young] we'd go forty minutes and never see a building. If you see anything it's a either a buffalo or a few horses or something else. There's nothing out there. The biggest laugh the movie gets is, especially from people like you and me, is when [Stacy Keach] is singing the song and he says "In the ghetto," you know? (Laughs) It's so appropriate and it's so honest and I think it's a wonderful portrayal of what's out there today and what has been there before.

It's funny, when we would go west it would we'd get almost halfway across Illinois, west of Rockford certainly by about a hundred miles, and everything became black and white from that time on. It was color, by the way, where you lived, except if you lived near Gary Fable High School or one of the high schools around there. I felt that that was honest and I think Alexander feels he wanted to tell the story honestly in black and white.

I think what you find out there is a fairness with the people and they don't lie, it's just that they are telling you stuff you can't quite believe is true.

You'd worked with Stacy Keach before, right?

[Note: In Nebraska Keach plays an old friend of Woody's; he's essentially the role Dern might have played in a different incarnation of this film.]

Yeah, we did a movie called That Championship Season. It was nineteen eighty-two. Martin Sheen, Stacy, myself, and Robert Mitchum. Jason Patric's father directed it, Jason Miller, who wrote the play [it was based on]. The play won a Pulitzer. For your trivia for today: the same year he won a Pulitzer, Miller was nominated for an Academy Award for playing what role in arguably the fourth or fifth biggest movie ever made, financially? He was Father Karras in The Exorcist. He's the priest that goes out the window.

How was it getting back together with Stacy for this?

What you see in the scene is exactly what went on, just like in That Championship Season. He was my buddy there and now he's fucking with me. Why would he do that? That's the way I look at him. That's the way he looks at it, because that's the reality of what's going on.