15 Movies To Watch If You Loved The Many Saints Of Newark

Tony Soprano feels about the same we remember him, but his presence in "The Many Saints of Newark" cuts differently. His looming presence is gone, replaced with a younger and more unsure Tony. You have to pay attention to the slight tilt of the head and his distinctive slouch to see the late James Gandolfini in his son, the young Michael Gandolfini, who takes over as our window into the world of the foundational TV series "The Sopranos".

At the time, that great, important show seemed like an entirely different type of gangster tale. With its preoccupations with dreams, psychiatry, and ducks, if the show told us anything, it was that the traditional gangster story could be told in the most untraditional way.

"The Many Saints of Newark," directed by Alan Taylor and co-written by "The Sopranos" creator David Chase is a snapshot of one era in that epic tale — part gangster movie, part fill-in-the-blank fanfare. Yes, it pulls its plot threads from a legendary series, but it stitches them together in a way that both recalls and dissects the gangster movie formula that has lasted for decades. If you're not familiar with the genre that "The Many Saints of Newark" draws from and deconstructs, the following films are an excellent place to start.

The Godfather

"The Godfather" is the standard-bearer that every former and current gangster story is judged against, including "The Many Saints of Newark." Its appeal lies in its memorable blend of moments and anecdotes: stallion heads in beds, public murders in restaurants, and stressful as hell hospital visits. It's also the quintessential portrait of the American dream, achieved by gangsters and delivered with a side of cannoli. The irony of director Francis Ford Coppola's saga being informed by Mario Puzo's novel of the same name comes in the fact that the film itself inspired a throng of books championing its greatness.

Case in point, this story about loyalty, family, bootstraps, and the immigrant experience, is about as foundational as any crime story can be: Aging Vito Corleone, played by the legendary Marlin Brando, is reaching the climax of his time as the leader of a crime family. He attempts to transition power to his son Michael (Al Pacino), only to be met with abject violence. As the "Godfather" shows, it turns out that stone-cold killers can actually be humanized to the point where we root for them. Go figure.

The Godfather Part II

The second Godfather film is bigger, bolder, and more sinister than the first because, well, that's an epic crime sequel should be. "The Godfather Part II" is as much about the rise of Michael Corleone as it is about the answer to a question: How did Corleone senior, an immigrant from lil ol' Sicily, manage to run an American crime family? It turns out that dirty hands help — in Vito's case, killing and thieving hands, to be specific. Gangster movie stalwart Robert De Niro plays a younger Vito, and pulls off a feat that some might view as a professional extreme: studying the Sicilian dialect to near perfection, then executing it in a way that seem effortless.

As much as a template as "The Godfather" was, Coppola stood at the height of his directorial superpowers with this sequel. "The Godfather Part II" also marked the first and only time that an original film and its sequel both won the Academy Award for best picture. Essentially, this is like defending chocolate over vanilla. Its greatness should speak for itself.

Infernal Affairs

As an adaptation, Martin Scorsese's "The Departed" may arguably be the better movie in just about every way — we can debate this endlessly — but there's something to be celebrated about being the chicken that came before the egg. Here, you've got the same unlikely story of an undercover cop planted within a mob family (Chen Wing Yan), and an undercover criminal planted within the police (Andy Lau). A game of undercover cat-and-mouse ensues until it spills onto a rooftop scene that Scorsese lifted almost shamelessly mood for mood. It's basically "The Departed" without all the Boston.

Almost nothing about co-directors Alan Mak and Andrew Lau's 2003 Hong Kong vision follows traditional rules, mixing violence with tension-filled moments of questioning silence. If "The Many Saints of Newark" is a flirtation with the language of betrayal, "Infernal Affairs" breaths it organically. In all his master classness, Scorsese owes a debt to the little Hong Kong thriller that inspired him enough to earn an Oscar. That isn't a slight. It's the truth.

A Bronx Tale

"A Bronx Tale" has a tasteful simplicity. An Italian boy (Lillo Brancato) grows up in the Bronx and narrates his story about the time he worshipped a local mobster (Chazz Palminteri). Yes, one can argue that his idol worship is questionable, but it's still one of the more historically great gangster movies, even with the lower stakes. "A Bronx Tale" is all glorious, coming-of-age excess — a sort of mafia movie answer to "The Wonder Years." Add in the hard-working, jealous father played by Robert De Niro, and it can even feel wholesome and insightful.

This film was Robert De Niro's directorial debut, and was based on Palminteri's 1989 off-Broadway triumph, a play based on Palminteri's own childhood on the streets of the '60s Bronx. At its heart, it's the same world as the one in "The Sopranos," portrayed from the vantage point of adolescence.

Goodfellas

Shoutout to the pretenders, because if Martin Scorsese's "Goodfellas" speaks to anything, it's the art of pretending: pretending to be a good husband, a good Italian, a good person; just a whole lot of "Sopranos"-levels of pretending. "The Many Saints of Newark" star Ray Liotta's performance as Henry Hill, a nobody special Brooklyn boy who sees a position within a mob family as a means for change, is his professional peak, but every character here is smooth, funny, and complex, from the comical but temperamental Tommy De Vito (Joe Pesci) to the deadly but tranquil James Conway (Robert De Niro).

To this day, author Nicholas Pileggi's source material captures the way made men loved, lived, and killed better than the majority of gangster stories out there. If a verbal battle between Tony and Livia Soprano ever brought you a peculiar joy, know that "Goodfellas" was the template.

American Gangster

What's great about "American Gangster?" It's the scene in which Frank Lucas, played by Denzel Washington, pops Tango (Idris Elba) in broad daylight. In a mere 5 minutes, Elba, who is all manifestations of debonair and cool, is reduced to nothing next to Washington. In a Russel Crowe-Washington combo that justifies the movie on its own, director Ridley Scott tells the story of Lucas, a Black businessman and a peddler of heroin who is seeking to rule Harlem, while Crowe is, of course, the Jersey cop looking to bring him down.

Like every other movie on this list, including "The Many Saints of Newark," "American Gangster" peddles America's fixation with power, while shifting it towards a Black American point of view. Frank is therefore as much of a villain as he is a human; this is the gangster movie in its most chaotic good form.

The Public Enemy

"The Public Enemy" is the gangster movie before gangster movies — and also if gangster movies were so ancient that they shot with live ammunition. William A. Wellman's "The Public Enemy" is partly listed because of Tony Soprano's obsession over the film in the "Sopranos" episode "Proshai, Livushka." But it also stands as a 1931 breakthrough hit that helped establish the basis of the American gangster film. To this day, it's educational as a viewing experience, but also as a relic of a time when the Academy Awards stood in the single digits — à la old as hell.

The storyline — Irish tough guy Tom Powers (James Cagney) tries his best to make it in the big bad Chicago world of organized crime — is mafioso worthy enough, but also raw for its time. The Great Depression was a decade old, and more than any other film, "The Public Enemy" sold audiences on the realities of crime under desperation.

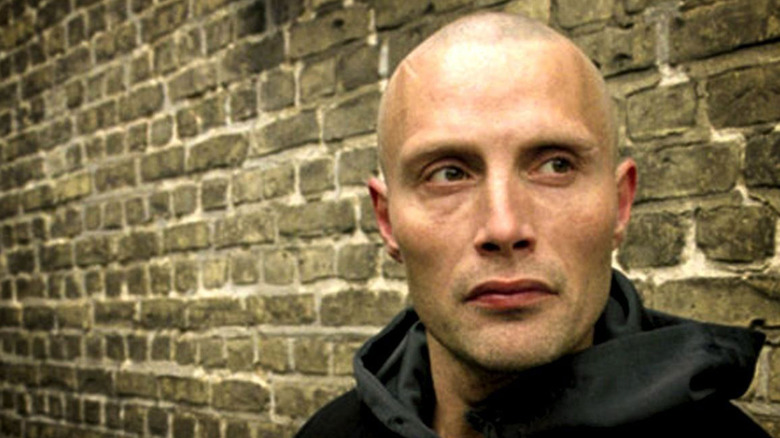

The Pusher Trilogy

The western mafia cliché about the "sympathetic" mobster is really tested in Nicolas Winding Refn's "Pusher" trilogy, which is set in Copenhagen. Now, obviously, Mads Mikkelson is impossible not to like under any circumstance — freakishly skull-headed and all — but it's still a ride to witness bad men making surprisingly redeemable transitions. The story is equally a trip: A drug dealer named Frank finds himself owing a debt to Milo, a Balkan kingpin, after he's led to believe that he's been betrayed by his chum, Tommy (Mikkelson). It's essentially hours of underworldly bits of cosplay by actors who manage to make this world entirely lived-in and breathable.

Refn's reading of a different class of gangland, free of tailored suits and fedoras, never garnered the same level of attention as most of the films on this list, but nevertheless earned a cult following. It's equally, if not more, worthy of praise within the lexicon of gangster films.

Mean Streets

Boy, it's hard to square ol' softy De Niro from "Meet the Parents" with his humorous badassery in Martin Scorsese's "Mean Streets," but times do change. It's a movie built on Scorsese's roots. The legendary director actually grew up in New York and observed the many personalities that walked and ruled the streets in the '70s.

Plot-wise, "Mean Streets" is a gangster-sympathizing instance of scrappy Catholics ruling their city by any means necessary. It was Scorsese's first film of this kind and demonstrated his operatic skills in managing legends, from a first stint with Robert De Niro to mafioso mainstays such as David Provel, Harvey Keitel, and Victor Argo.

It's also as much a movie about expectations and values in the glare of an easily corruptible city. Maybe it isn't Scorsese's most paraded film, but the formula is sound. Director Scorsese? Legendary filmmaker. Writer Mardik Martin? Legendary writer. Actor De Niro? You get the picture.

Gomorrah

How many times can you watch a gangster movie and say, "I've never seen anything like this," as man number *insert digit* is murdered? Probably never. What "Gomorrah" lacks in redeemable characters it makes up for with the unredeemable. You've seen a dozen mafia stories about anti-heroes and ambiguous villains, but director Matteo Garrone's film is not one of them. The organized crime is clear; it's about money. Audiences see the money, but rarely sense the riches.

In seemingly unrelated storylines, a movie set in a stronghold for the Mafia of Naples will shift from best friends who pinch a cache of semi-automatic weapons to deadly delusions of grandeur. Violence in the name of day-to-day normality lives here. A man pulling up alongside a sedan before opening fire, for example, isn't exploitative, but completely normalized in this world, making misdeeds all the more authentic. Five writers, including Garrone, adapted "Gomorrah" from the unbelievable nonfiction depiction of Naples under the control of a local crime syndicate, the Camorra. Taken purely as a gangster film, it's an amazing experience to behold.

Once Upon a Time in America

The mammoth spaghetti western legacy of director Sergio Leone doesn't keep this gangster movie from being his magnum opus. At its best, "Once Upon a Time in America" marshals the same indictments around criminal life amid the gentleness of family — very "Newark." It stars Robert De Niro, De Niro'ing his way into another mobster role about betrayal as Noodles, a Manhattan youth who rises through the ranks of organized crime, only to become increasingly desperate as the end of Prohibition cuts off his cash flow.

And remember this: the aired version was cut down to 139 minutes from a four-hour epic. Understandably, Leone's vision faced critical and financial failures due to the pacing and lost sections of character development. Over the years, those cuts hurt its place next to "The Godfather" and other greats, until it was restored to a full 250-minutes in 2012.

Casino

There are only so many times one can type the name "Martin Scorsese" before it gets old. In the case of this entry, Scorsese had a key to the city in the most Hollywood-like way. He was fresh off of a $47.1 million earning with "Goodfellas," so why not portray some other fellas at every mafioso's favorite playground: a casino.

Much of Scorsese's work revolves around self-harm in the most unintentional ways. A casino, with gambling and, you guessed it, betrayal as the catalyst, was an ideal setting for the theme. Inspired by the non-fiction story of Mafia connection Frank Rosenthal, you have a casino manager known as Ace (Robert De Niro), with scheming enforcer Nicky (Joe Pesci) and hustler wife Ginger (Sharon Stone). Things happen, terrible decisions are made, and thus you have the much-esteemed "Casino."

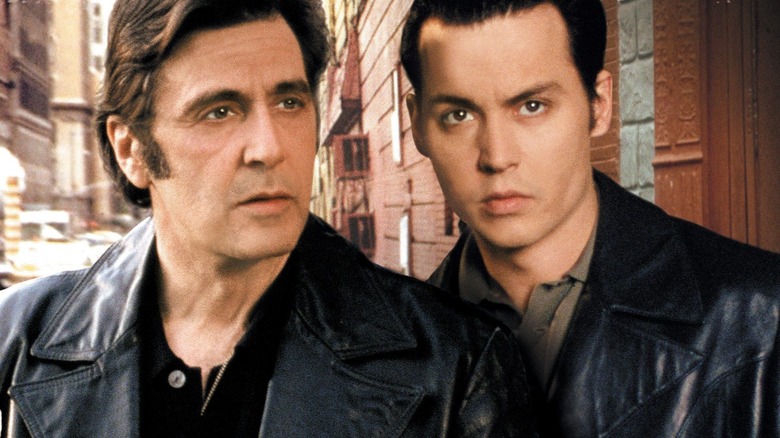

Donnie Brasco

Orange juice and tequila, whirling together in a glass of grenadine to make up a Tequila Sunrise. That's the image that came to mind when Al Pacino and Johnny Depp joined together — subtle sweetness, warmth, and intensity. In Mike Newell's calming but still violent true-to-life portrait of an undercover mob investigation, both Depp as FBI agent Joe Piston and Pacino as mobster Lefty Ruggiero dish out unforgettable performances of riffs and wits.

This isn't the average gangster movie featuring hard-knock characters as super-villains. It's about flawed men, dwindling dreams, and an agent who falls victim to the humanity of a crooked man. Mobster films rarely spend time with the low-level gangsters who hover under the shadows of their bosses — think Paulie Gualtieri in "The Many Saints of Newark" — but "Donnie Brasco," with all its New York Mafia vibes, is one of the few great exceptions.

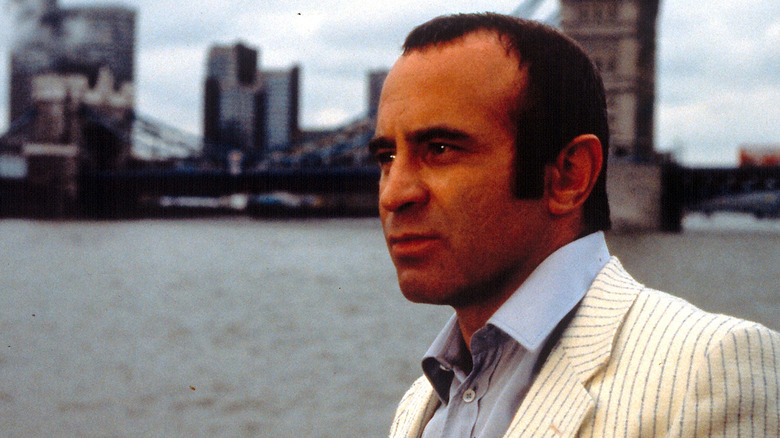

The Long Good Friday

Some gangster movie personalities have all the answers. Others just have balls. Harold Shand (Bob Hoskins) in the '80s London great "The Long Good Friday" has balls, but with feeling. He's no crime lord — when the film begins, he's even trying to go straight — but he responds when clubs are bombed and family murders happen, trying to hunt down the men responsible. It's in the moment every movie crime family fears: when the collapse is steady and the offenders are obscure.

Thanks to the direction of John Mackenzie, Shand is given the allowance to feel muddled, fearful, and furious as tragedies present themselves like trickling domino effects. If the finale of "The Sopranos" had a feeling of mounting and inescapable dread, it's personified in this British classic.