Saltburn Director Emerald Fennell Wants You To Be Disturbed – But Also Aroused [Exclusive Interview]

"Saltburn" is a movie designed to get under your skin and make your morals itch. And that's clearly director Emerald Fennell's speciality.

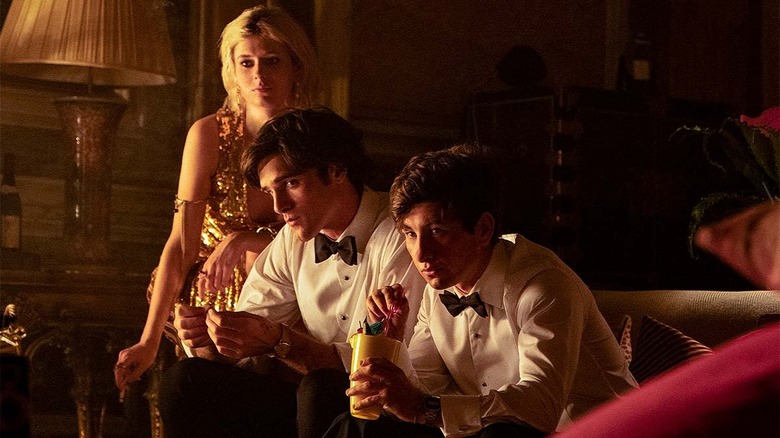

After snagging an Academy Award for writing her directorial debut, the unsettling thriller "Promising Young Woman," she's back with another movie that feels designed to inspire all manner of post-movie conversation. Like it or not (I liked it a great deal), "Saltburn" is not a film that just washes over you. It lingers and burns. It sets out to make you uncomfortable, to make you complicit in the darkly hilarious and frequent tragic misadventures of Oliver (Barry Keoghan), a young man whose absurdly wealthy college friend invites him to stay at the family manor for the summer. Lots of ... well, lots of really wild stuff occurs, to put it mildly. And while much of it is disturbing, Fennell wants you to know this: It's okay to also be turned on by it all.

I spoke with Fennell from the Austin Film Festival, where "Saltburn" was screening. During our all-too-short conversation, we talked about casting rising star Barry Keoghan, the DNA her film shares with an Alfred Hitchcock classic, the one thing that really drives her nuts about people's reactions to her movies, and, of course, the film's audacious ending.

"Saltburn" is in theaters today.

'He'll burrow under your skin and hide under your bed and then he'll pop out'

Over the past few years, Barry Keoghan's become a bit of an institution. He keeps popping up in great movies.

Yeah. He'll get anywhere. He'll burrow under your skin and hide under your bed and then he'll pop out.

He's gone from being an actor we like, to one people are obsessed with. How did you come to cast him and what was the experience like?

I'd seen "The Killing of a Sacred Deer" and "Calm with Horses" and all those, and like everyone who watched that movie and who's seen him perform, I just thought, Who is that? What is this performance? I've never seen anything so electrifying in my life. Somebody who's just so patently a, I don't know, charisma machine. I was so fascinated. And I've been thinking about "Saltburn" for a long time. And actually it wasn't until after I delivered [the script] and we started talking about casting that I thought of Barry, because in many ways, when it comes to this kind of genre, when you're looking through "Brideshead" and all of those kinds of things, it's a lot of doppelganger stuff. So you'd be looking to maybe cast people who felt similar. And then I think early on, I started thinking about Barry and thinking, Well actually, it's more interesting to have somebody who's actually kind of a stealth missile in a way, somebody who you maybe don't see coming.

So I sent him a script and I met him and I immediately loved him. The way that I like to work with actors — not just actors, though, any head of department — is I like to get to know them, which sounds so twee and silly, but I mean, ask questions. If I meet actors, for example, I'm wanting to see if we're going to have an honest conversation, if we're going to be able to be honest with each other, if we can get into the place which is exciting. So I'll ask things like, "Do you really like being famous, for all your protestations?"

It's interesting, and some people are like, "Yeah." And then you're like, "Okay, great, we can have that conversation." Or you ask, "Do you prefer your mother or your father? Which one would you mind least if they died?" Whatever it is, the kind of things that you want to see if people are going to ... there are lots of actors who are amazing, but they're naturally reserved, and they don't want to give you that stuff. But Barry, he came in and we were just right into it right away. But I hadn't seen him do an English accent. So I asked to see an audition. I asked his team if he'd auditioned for anything with an English accent that I could see. And he had a few years ago. And it was so interesting, it was just the same thing. It was just him in a room, not off book or anything, just reading the lines of something, actually quite a surprising thing.

It was just that sensation of, by the end of the audition, my nose was practically touching the screen, because the thing with Barry is the more you show him, the closer you show him, almost the more enigmatic he becomes. He's sort of a close-up magician. You can just watch him, and something's happening that's magic, but it's impossible to see what it is or how it is. Making the whole film was like that all the time. There were still days when I was like, "F**k, how does he do that?" Especially at the moments when we were most furious with each other and we most wanted to push each other off a cliff, then it'd be like, "Oh wow, yeah."

'We don't like to admit if we're aroused by something disturbing'

Hearing you talk about the questions you asked him, it's like you're trying to push his buttons to figure out what reaction he's going to give you. I remember when "Promising Young Woman" came out, I heard passionate arguments from folks about the movie and what it put them through. And I think "Saltburn" is going to inspire similar reactions — people are going to be angry about it or laughing about it or just moved by it or saddened by it.

Or turned on. Crucially.

Is that one of your goals as a filmmaker? To be provocative, to inspire debate?

It's a really difficult one because it's hard to talk about it without sounding facetious. But it's very easy to be provocative. I mean, you could show all sorts of stuff and get a reaction from people. The thing that I'm interested in is making people emotionally connect with something that's difficult. And it is the same with the thing about this movie. Actually, when you break it down into pieces, there's a reason it's not NC-17, it's because you don't actually see very much. A huge amount of the more transgressive scenes, in fact, all of the transgressive scenes between two people are shoulders up. It's all our imagination. And the nudity isn't about sex, it's about joy or triumph or grief. So it's an interesting one about shock and how it's used. I think I'm more interested in asking people why they feel the way they feel about things, why they forgive some people their behavior because they're beautiful, and some people don't get away with things. Why we don't like to admit if we're aroused by something disturbing.

It's not useful unless it's personal. So if it's personal to me, it's likely to connect with other people. But then it's also likely not to, because if you make something personal, in the same way that there are lots of people that you could be friends with and there are lots of people that you couldn't talk to. When you're dating, you connect with people and you don't. I'm not setting out to be provocative because I think that would be quite boring. But I'm setting out to be honest and unsparing, and I'm not frightened of people not liking it. I mind if people don't appreciate the craft or they think I haven't done my homework, or they think I've made decisions that aren't deliberate. That gets my goat, because that's a different argument. But if you don't like it, I don't mind.

It's a very different movie, but I can't stop comparing "Saltburn" to "Psycho," the original Alfred Hitchcock film. In that movie, you don't realize that you want Norman Bates to get away with it until you see him trying to sink the car, the evidence of murder, in the lake. And I realized, at some point, the filmmaker asked you to cross a line where you're rooting for behavior that, an hour ago, you wouldn't have been rooting for.

Totally.

Is that something you had in mind when you were crafting "Saltburn"?

Always. ["Psycho" star Anthony Perkins] was also a heartthrob. That's who Alfred Hitchcock cast, a heartthrob, teen heartthrob, for that part. People forget that because ["Psycho" is] what he's so famous for, and it kind of, in many ways, made his career very difficult after that because nobody could ever see him as anything but sinister. But before that, he was a beautiful boy that everyone fancied. That kind of decision is so crucial for that empathy and that connection and that using of an audience's prior relationship with genre, with an actor, is something I always love to do.

But also, again, similarly with "Promising Young Woman," it's following a protagonist that then departs at one point, who suddenly is no longer ... they're not going to be the engine of the story. So I mean, he's a perfect example of somebody who is very, very aware that every decision can squeeze a different feeling out of an audience.

'You left the film feeling shaken up and complicit and thrilled'

This final question contains spoilers for the ending of "Saltburn" and you should not read it until you've seen the movie. Seriously.

Everyone who has seen the movie can't stop talking about the ending, and specifically the final shot. Where did the final shot come from? How'd you shoot that?

It was always in the script, it was a naked walk through the house, and then about halfway through the shoot, because we were so lucky that we were there, it was always going to be the inverse of Felix's tour, that we see the house and then we see Oliver's tour of the house later. And it just felt halfway through shooting that it wasn't going to give up, it was going to just feel like a saunter, didn't feel like desecrating or an act of territory-taking and all of that kind of stuff. But also, it needed to feel like post-coital and joyful and that if people weren't all-in on Oliver already, as I am, then it was going to be inarguable that at least you left the film feeling shaken up and complicit and thrilled.

Because I think that's the thing, you are always wanting to push how far people are going to extend their empathy. So it needed to feel like, "F**k yeah." It needed everyone at the end to be like, "Take them, take them all down." "Kind Hearts and Coronets," all of those graves, just boom, boom, boom. Just be like, "Okay, why not? Why not?" And so it needed to be jubilant, and I thought [the song] "Murder on the Dancefloor" was just the perfect amount of camp and self-aware versus an actually joyful and thrilling. And it was incredibly difficult to do because obviously it's a oner, and we had to light every room completely from outside without seeing any of the kit. We had to set up all of the sound so we could switch to every room because of the lag, without again, seeing any of the kit.

And then obviously, the distance with the cameraman, and Barry had to be very, very specific. And Polly Bennett choreographed it, so it was very important that it felt clean and precise, but with the perfect amount of spontaneity and joy that made it feel both like a fantasy sequence and something like somebody might do in a moment of spontaneous evil glee. So it just took a long time to get that. That was the eleventh take. But it's just a joy when your crew, when you're all-in on something. And we all really were, including Barry. It's also difficult because, of course, it's a closed set so nobody else can see it, it's only me and [cinematographer] Linus [Sandgren], and the script supervisor, and Polly, the choreographer could actually see it, as well as the skeleton crew following him. So there's also this fascinating thing of everyone's doing their job, but nobody can see what they're doing. Yeah, it was just amazing.