The 15 Best Japanese Action Movies Of All Time

Yakuza tales drenched in revenge and bloody samurai epics are what most people think of when asked about their favorite Japanese action movies. They wouldn't be wrong, either, as both are essential components of the genre. Japan has one of the oldest film industries in the world, with Thomas Edison's kinetoscope first imported in 1896. Between 1909 and 1928, director Makino Shozo began pumping out films, popularizing period pieces known as jidaigeki.

I bring up jidaigeki movies because they reached new heights by the mid-1940s, thanks to Akira Kurosawa. Kurosawa is the gateway to Japanese cinema for many Western audiences. This legendary director incorporated action into his period epics that have since influenced filmmakers globally.

Of course, Kurosawa is merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Japanese action films. What fascinates me about these movies is the deep saturation of culture throughout. Filmmakers take their time with certain scenes, focusing on atmosphere and beauty. We see tender familial moments set in tatami rooms and characters floating in silence through cherry-blossom-lined streets. This delicate lifting of the kimono juxtaposes with violent passion as our protagonists fight for justice and honor. Above all, two prevailing themes in the genre revolve around tradition and humanity. Let's look at 15 of the best Japanese action movies of all time, from jidaigeki classics to films set in the criminal underground.

Seven Samurai

You can't discuss action movies without mentioning Akira Kurosawa's 1954 masterpiece, "Seven Samurai." This Japanese opus is a near-perfect film, gripping you for its entire three-and-a-half-hour runtime. We're introduced to the rōnin Kambei (Takashi Shimura), who is called upon to aid a defenseless village against a group of bandits. From there, Kambei finds six ragtag samurai to help him as they prepare for war while training the townsfolk in combat.

The final, monsoon-soaked battle is mesmerizing, with the rain only heightening the bedlam. With all the chaotic action, Kurosawa knew that using a single camera and filming multiple perspectives would be extremely difficult for continuity. Instead, he innovatively incorporates long lenses and multiple cameras to fill scenes with depth. The result is beautifully composed, with the visual layers making everything seem utterly cinematic.

From a storytelling perspective, most of the dialogue found in "Seven Samurai" is simplistic, but the theme of community still resonates today. This is a tale about two groups of people forced into cooperation. The hungry samurai agree to fight in exchange for food, while the villagers, mistrusting their sudden allies, have no choice but to band together. As Kambei wisely declares, "This is the nature of war: By protecting others, you save yourselves."

Tokyo Drifter

You'd be hard-pressed to find a slicker movie than 1966's "Tokyo Drifter." Seijun Suzuki's unhinged yakuza delight was light years ahead of its time, incorporating bursts of color, surrealism, and, oddly enough, musical montages. "Tokyo Drifter" can sometimes feel like it has more style than substance, but can you fault Suzuki when everything looks so darn cool?

The premise is deceptively simple. Tetsu (Tetsuya Watari) and his yakuza boss have declared they're going straight and leaving their criminal lives behind. Yet, when a rival mob wants to recruit Tetsu, he declines, infuriating the oyabun. Our hero finds himself on the run from an assassin, "drifting" through the countryside, all while casually taking out whichever lowlife crosses his path.

Suzuki had a lot of fun shooting this indulgent yakuza flick. The production design is imposing, with nightclub scenes lit up in a lavender glow, while a Western-inspired saloon brawl may be the most chaotic bar fight I've ever witnessed. Suzuki makes his sets as disposable as yakuza gangsters, allowing his gangsters to shoot through walls, the floor, or anywhere their trigger fingers fire. Tetsu is handily the best part of "Tokyo Drifter," displaying effortless swagger in his powder blue suit while whistling his theme song en route to annihilate some baddies.

Yojimbo

Akira Kurosawa made over 30 movies during his career, yet none were as profitable as his 1961 samurai hit, "Yojimbo." Kurosawa was a huge fan of Westerns, and you can definitely spot the John Ford influence in his lone hero wandering into a town and restoring order.

In 1860s Japan, a wandering rōnin, who assumes the name Sanjuro (Toshirō Mifune), comes across a village. With two rival gangs vying for control, this small community yearns for peace. A seemingly amoral Sanjuro is amused by what he sees and decides to side with both factions. From there, he takes delight in cleaning up the village, using his sword to enact justice. The action sequences in "Yojimbo" are a meticulously choreographed feast for the eyes. Kurosawa doesn't take any of this too seriously, purposefully adding exaggerated sound effects such as the rattling sound of a jawbone getting hit or a sword slicing through flesh.

Like all of Kurosawa's films, "Yojimbo" has a timeless theme. "Now it will be quiet in this town," Sanjuro calmly declares at the movie's end, telling us that the only way to eliminate societal corruption is by dismantling it altogether.

Love Exposure

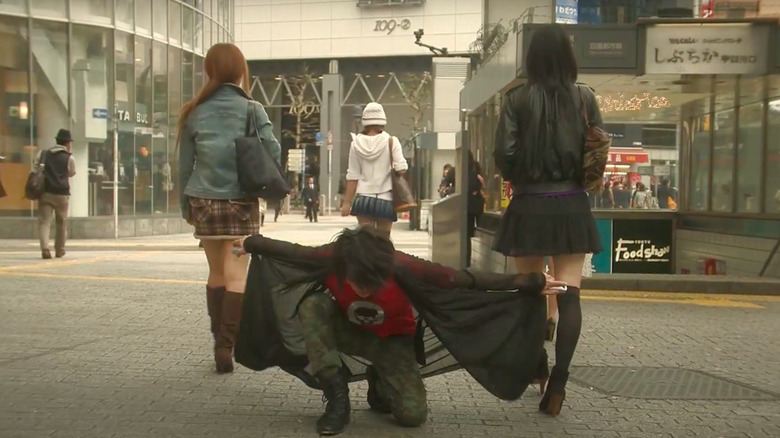

Few movies that clock in at four hours are as exhilarating as Sion Sono's upskirt epic, "Love Exposure." It's difficult to summarize this twisty action-comedy, as it can come across as a perverse, nonsensical tale. Yet, somehow, the scope of this film works, with an emotional payoff at the end that left me sobbing.

Yu (Takahiro Nishijima) is a troubled teenager whose mother has unexpectedly died, leaving him and his Catholic priest father, Tetsu (Atsuro Watabe), to rebuild their lives after tragedy. Yu's father eventually moves on. However, after a new flame breaks his heart, he spirals into a rage. Taking his frustrations out on his son, Tetsu forces him to confess his sins daily. Of course, the 17-year-old doesn't have much to confess, so he ups the ante by purposely sinning. Eventually, he becomes an upskirt photographer, but Yu is no average shutterbug. He trains in this voyeuristic art, wielding his camera like nunchucks with kung-fu-style acrobatics. After losing a bet that results in a brief cross-dressing stint, Yu falls in love with a girl named Yōko (Hikari Mitsushima) — his "Virgin Mary." Although he feels guilt about his new profession, Yu cannot deny his sudden, primal lust.

"Love Exposure" uses this frenzied plot to tackle challenging themes such as religious dogma, sexual abuse, familial trauma, and Japan's powerful patriarchy. Through all of this, Sono tells us that love conquers all — no matter how harrowing our sins are.

Ichi the Killer

One of the most violent action movies ever made, "Ichi the Killer" is so depraved it was banned in several countries after its 2001 debut. Dismissed by critics as misogynistic, exploitative, and brutal, the film by director Takashi Miike does something quite clever: It doesn't take a moral stance on what's unfolding on screen. Instead, Miike forces his audience to ask themselves what their attitude is towards this savage tale.

Based on the manga of the same name, "Ichi the Killer" introduces us to Kakihara (Tadanbu Asano), a yakuza enforcer who is so deranged he blows cigarette smoke through his perforated cheeks. Kakihara loses his boss, sending him into a spiral as he searches for the only person he's ever viewed affectionately. Interestingly, this thug is our protagonist — not the titular character.

Ichi (Nao Omori) has been psychologically brutalized by his oyabun, Jijii (Shinya Tsukamoto), and made into a weapon void of personal identity. When Kakihara realizes Ichi may have murdered his boss, the two engage in a wanton cat-and-mouse game. With "Ichi the Killer," Miike declares that we're all voyeurs. His violence is gratuitous. Yet, that's what draws us to this visceral canvas.

Lady Snowblood

If you're a fan of the "Kill Bill" saga, you must have heard of "Lady Snowblood." Quentin Tarantino borrowed heavily from this jidaigeki gem, with the iconic fight between the Bride (Uma Thurman) and O-Ren Ishii (Lucy Liu) in "Kill Bill: Vol. 1" lifted almost beat-for-beat from the 1973 film.

Set in late 19th-century Japan, the revenge classic sees Yuki (Meiko Kaji) on a quest to avenge the deaths of her family, going down her list of targets much as the Bride does in "Kill Bill." Yuki was raised with the sole purpose of revenge, and we even get flashback scenes with the nascent eight-year-old killing machine. In adulthood, our heroine is beautiful yet stoic, carrying a sword hidden in the handle of her parasol.

The action in "Lady Snowblood" is violent but also beautiful. Set against a snowy winter backdrop, the torrents of blood are even more vivid against the pristine white scenery. Soaked in carnage, "Lady Snowblood" also features my favorite cinematic sword-slicing scene: a gracefully executed slash through a human piñata.

Battle Royale

The premise of the dystopian classic "Battle Royale" sounds very similar to the beloved "Hunger Games" franchise. Trust me when I tell you that this 2000 gem is infinitely more action-packed and brutal. According to "The Mammoth Book of Slasher Movies," the film was deemed too disturbing at the time of its release, with censors fearing it would incite real-life violence among teens. However, director Kinji Fukasaku firmly believed that Japanese youth would benefit from the message of "Battle Royale," so he released an edited version to theaters for audiences 15 and up.

In the not-so-distant future, the tyrannical Japanese government institutes the "BR Act." This law allows them to pluck 42 ninth-grade students each year and send them to a remote island. Once they arrive, the students each get one random weapon and a collar that explodes if they try to escape or cheat. The only way to survive is by slaughtering each other.

More than just an action movie, "Battle Royale" is important social commentary. Representing the divide between two generations in Japan, our young heroes are lost, with no role models to turn to for help. Their teacher, Kitano (Takeshi Kitano), isn't respected by his students, while one of our leads, Nanahara (Fujiwara Tatsuya), tragically lost his father to suicide. These adolescents aren't out of control by choice. They're a byproduct of an authoritarian upbringing.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Branded to Kill

Borrowing elements from the French New Wave movement and inserting moments of sheer Luis Buñuel-style absurdism, 1967's "Branded to Kill" earns Seijun Suzuki the spot as my favorite yakuza genre filmmaker.

Gorô Hanada (Jō Shishido), a hitman with a fetish for sniffing steamed rice, botches his most recent assignment when a butterfly lands on the barrel of his rifle and causes him to miss his target. He suddenly finds himself stripped of his rank and on the run from another assassin. With fast-paced action sequences, symbolic visuals, and intense moments of passion, Suzuki hurls everything in his arsenal at you during this film's 90-minute runtime.

While undoubtedly captivating, "Branded to Kill" can be hard to follow. Suzuki favored American noir-style storytelling and injected it into this beloved B-movie, forcing his audience to follow a non-linear narrative that incorporates unconventional camera angles. Unfortunately, this influence landed him in hot water with his production company, Nikkatsu. "We don't need a director who makes movies nobody understands," declared company president Kyusaku Hori (via Asian Cult Cinema). Suzuki had been on thin ice for years, and "Branded to Kill" was, unfortunately, the final nail in the coffin for his career at Nikkatsu.

Akira

You can't discuss Japanese action movies without mentioning Katsuhiro Otomo's 1988 masterpiece, "Akira." Considered one of the most important anime movies of all time, this cyberpunk classic has influenced filmmakers worldwide.

Set in dystopian Neo-Tokyo in 2019, the city is crumbling due to a psychic blast unleashed by the titular character 30 years before. Ravaged further by gang wars and protests, Neo-Tokyo finds itself in even more peril when biker gang member Tetsuo (Nozomu Sasaki) gains the same psychic powers as Akira — and let's just say he isn't using them for good. Frantic, Tetsuo's former friend, Shōtaro (Mitsuo Iwata), must work with the corrupt government and rebel factions to prevent destruction.

"Akira" was the first anime I ever saw, and to this day, it holds up. The amount of anxiety I feel, even during subsequent viewings, is simply unparalleled. Filled to the brim with insane imagery like the gigantic milk-oozing teddy bear that springs to life and the grotesque final act involving Tetsuo, this legendary anime is a nail-biting experience. "Akira" rocks, and while it's been endlessly imitated, there's nothing quite like it.

Battles Without Honor and Humanity

A year after Francis Ford Coppola captivated audiences with "The Godfather" in 1972, Japan released its own version of a sprawling gangster epic — "Battles Without Honor and Humanity." Much like "The Godfather," there are multiple entries in this saga, but don't be fooled. These are not chivalrous tales. Until the late 1960s, Japanese action flicks portrayed yakuza as men with strict moral codes. However, the new decade gave birth to jitsuroku eiga, movies which depicted gritty gang wars based on true events (via "A Companion to the Gangster Film").

The first entry in the "Battles Without Honor and Humanity" series perfectly represents the jitsuroku eiga film. As the opening shot of a mushroom cloud followed by a ruined Hiroshima appears on screen, it doesn't take long to realize that there is no humanity here. We follow Shozo (Bunta Sugawara), a former soldier in postwar Japan, as he rises in the ranks of organized crime. Throughout it all, Shozo navigates assassinations and gang fights aplenty while questioning his alliances.

Told through hectic, documentary-style cinematography, you'll need to pay attention to this one. I'm not joking. Director Kinji Fukasaku immediately throws you into utter bedlam, and if you can't figure out what's going on, well, too bad. If you're looking for constant action that's bloody, bleak, and downright exhausting, "Battles Without Honor and Humanity" is for you.

The Sword of Doom

Kihachi Okamoto eschewed familiar jidaigeki tropes with the release of 1966's "The Sword of Doom," which presents us with the most amoral antihero in samurai movie history. Okamoto delivers irredeemable brutality in what can be seen as the antithesis to Akira Kurosawa's noble period epics.

With soulless eyes and a disturbing smile, the samurai Ryunosuke (Tatsuya Nakadi) leaves a bloody trail of death during the final days of Japan's Shogunate rule. As vendettas grow and the bodies pile up, Ryunosuke descends into madness. At the film's start, we see an old Buddhist man praying for death, only to have Ryunosuke grant his wish seconds later.

In Japan, the title of this action classic is translated to "Great Bodhisattva Pass," which brings up the film's spiritual undertones. In the final shot (which I won't spoil), we see that Ryonsuke has fully transformed into a primal and hopeless animal. Okamoto shows us that for a man this depraved, there is no retribution. He is stuck in his own violent samsara. It's a powerful, haunting moment.

The Street Fighter

Released in 1974, "The Street Fighter" is an action movie so iconic, Capcom named their legendary arcade game after it. This Shigehiro Ozawa-directed film spawned two sequels and numerous spin-offs. Still, the original remains the best. Complete with eyeball-gouging, skulls being shattered, and some, ahem, ripping of the genitals, "The Street Fighter" was the first film to earn an X rating in America due to its violence. As the movie's tagline warns, "If you've got to fight — fight dirty."

We meet Takuma Tsurugi (Sonny Chiba), a martial arts master who also happens to be an assassin-for-hire. Both the Mafia and yakuza ask him to kidnap Sarai (Yutaka Nakajima), the daughter of a dead billionaire. When these seedy gangs refuse to pay Takuma's fee, he decides to protect her, all while battling whoever crosses his path.

Chiba was Japan's answer to Bruce Lee, and there's no doubt that this well-received film cemented his status as a martial arts giant. When I watched "The Street Fighter" for the first time, I was blown away by how outlandish the fight sequences were. Featuring perfectly choreographed fights blended with laugh-out-loud facial expressions from Chiba, you can't help but be impressed by the creativity of it all.

Why Don't You Play in Hell?

If you're on the hunt for some truly bizarre yet action-packed movies, Sion Sono consistently delivers. Known for his cartoonish characters, bursts of color, and imaginative violence, the director is a cult figure in modern Japanese cinema. 2013's "Why Don't You Play in Hell?" serves as an excellent entry-point for those unfamiliar with Sono's work, as he strays further away from the experimental (think "Love Exposure") and dives deeper into comedy.

Led by the passionate aspiring director Hirata (Hiroki Hasegawa), a teenage movie crew, who call themselves the F*** Bombers, are eager to sharpen their guerrilla-style filmmaking skills. Hirata prays to the "Movie God," declaring that he's willing to die in exchange for one great film. Fast forward 10 years later, and he's still trying to achieve his dream. However, this time, the F*** Bombers find themselves in the middle of a yakuza battle — and one of the organizations hires them to film some real-life carnage.

The gags and movie references are never-ending, so to catch them all, you'll need to keep up with all the lunacy. Drawing inspiration from both Quentin Tarantino and Takashi Miike, "Why Don't You Play in Hell" is a joy to watch and a glorious ode to all the struggling filmmakers out there.

13 Assassins

Fair warning: "13 Assassins" starts slow — especially for an action flick. Just hold fast, as you'll soon witness the most beautifully choreographed and engrossing fight sequences ever filmed. A remake of a 1963 movie of the same name, "13 Assassins" was directed by Takashi Miike, who injects this version with his signature savagery in the final act. It's exhilarating. It's bloody. And it's guaranteed to assault your senses.

In Shogun-era Japan, Lord Naritsugu Matsudaira (Goro Inagaki) commits unthinkable crimes against his people as he tries to take the throne. Thankfully, a group of the finest samurai is hired by a government official to take him out.

I'd be remiss if I didn't say this plot sounds a bit like Akira Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai," but the granddaddy of jidaigeki classics was never this vulgar. Lord Naritsugu is evil incarnate, and I'm convinced that only Miike could craft such a sadistic character. "13 Assassins" may not be as celebrated as his horror magnum opus, "Audition," but it's an impressive movie that's sure to satisfy any action enthusiast.

Sonatine

While Takeshi Kitano has directed some fantastic movies, he's best known as one of Japan's most celebrated comedians. Perhaps it's Kitano's background as a funnyman that instills such a refreshingly light-hearted aspect to 1993's "Sonatine." A yakuza flick that feels like the lovechild of Haruki Murakami and Martin Scorsese, "Sonatine" is reflective and existential, focusing more on the relationships of its characters than sheer explosive violence. That said, when he does hit you with bloodshed, it's detached, and that's precisely what makes it so shocking.

Kitano plays Aniki Murakawa, a middle-aged yakuza underboss debating going clean. Murakawa's bosses send him, along with a band of young underlings, to Okinawa to take out a rival gang. After they're ambushed, our hero suspects foul play. Deciding to hide out at a beach house until they figure out their next steps, Murakawa and his men pass their time playing games, putting on shows, and acting like, well, normal people. Once the gang starts getting picked off, Murakawa turns into a killing machine.

"Sonatine" is an action movie with heart, and Kitano adds a lot of depth to characters that other directors may have made disposable. The slower scenes are poetic, and whenever we're shown sudden, deadpan violence, we're grounded back in reality.