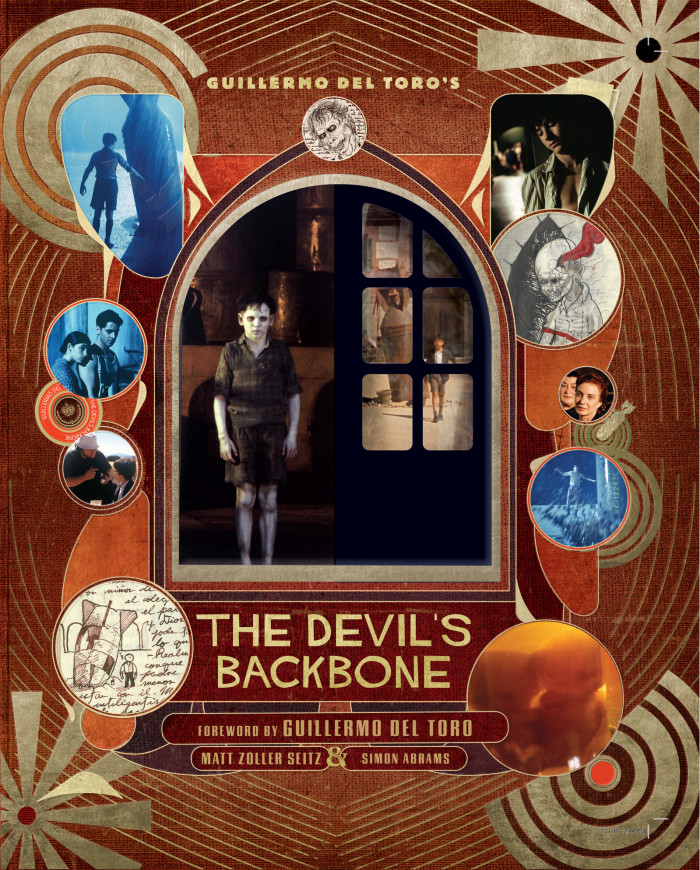

'The Devil's Backbone': 13 Revelations About Guillermo Del Toro's Masterpiece From An Incredible New Book

Matt Zoller Seitz and Simon Abrams have created a stunning, essential new book devoted to Guillermo del Toro's 2001 gothic horror movie The Devil's Backbone. Through in-depth interviews with del Toro and the cast and crew of the film, the Devil's Backbone book details both the making of one of del Toro's best films, and del Toro's insights into filmmaking as a whole.In 1997, Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro went Hollywood with the horror film Mimic. It didn't go so well. del Toro had burst onto the scene with his haunting, unique, inventive twist on vampire mythology, Cronos. It made sense that Hollywood would come calling, but del Toro's jump into the "mainstream" was fraught with production woes, meddling producers, and a finished product that left much to be desired. The filmmaker was down, but not out.Del Toro would reclaim his artistic integrity (and peace of mind) with the Spanish language gothic melodrama The Devil's Backbone. Released in 2001, it was a firm reminder that the budding genius many people had sensed watching Cronos was still alive and well, and that Mimic hadn't sapped del Toro of his powers. The Devil's Backbone would be the first of two films del Toro would set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War, the second being Pan's Labyrinth. It might be easy for some to think of Backbone as a test-run for Labyrinth, but that would be doing a disservice to the former. Instead, the film's compliment each other, like mirror images. But Devil's Backbone is still very much its own unique beast.On its surface, The Devil's Backbone is a ghost story – the tale of a lonely boy who comes to an orphanage and finds a ghost. But there's so much more going on here. Characters are never one-dimensional in a del Toro film – there are no real heroes or villains. Instead, there are just people, full of conflicts, and neurosis, and hopes, and dreams, and hatreds. These elements are all at play in the cast of characters that populate The Devil's Backbone, and through them, del Toro weaves a haunting, hypnotic, heartbreaking tale.In Matt Zoller Seitz and Simon Abrams' wonderful new book, del Toro's comeback film is explored from every angle – pre-production, production, and beyond. The film's very soul is laid bare through a book-length interview with del Toro himself, interspersed with interviews from various members of the cast and crew. It is an all-encompassing look at a remarkable film, but it's more than that. This book is like an entire journey through film school condensed into 160 pages. Del Toro doesn't just talk about Backbone – he talks about the medium of film as a whole, and shares his thoughts on other filmmakers.Anyone who has listened to one of del Toro's Blu-ray commentary tracks knows how well-versed in the language of film he is, and here in the pages of The Devil's Backbone is even more of his staggering knowledge and insight. It's an utter treat, not just for del Toro fans but for film fans in general. I've combed through the pages of The Devil's Backbone and assembled some wonderful revelations for you here. But these tidbits only scratch the surface. For the full experience, you really must get your hands on the book.

An Antidote

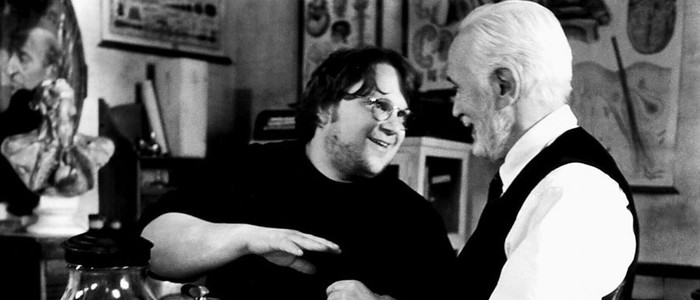

Mimic should've signaled Guillermo del Toro's big arrival in Hollywood. Instead, the film's troubled production – which included meddling from producer Bob Weinstein at Miramax – and tepid reception was an overall crushing experience for the filmmaker."From the get-go, it was a bad experience," del Toro says in The Devil's Backbone book. "I was in post-production on it for two years, and coming out of that I honestly thought, Maybe I'm not made for this, because [Miramax cofounder] Bob Weinstein was very tough to survive."The filmmaker goes on to say that, at the time, the Weinsteins were considered "golden" in the industry, and that most people assumed the faults in Mimic must have sprung from del Toro as a filmmaker rather than Weinstein interference. "Eventually, over the years, more information emerged," del toro says. "But at the time people said, 'God knows what happened on Mimic.'"After Mimic, del Toro found American film work hard to come by. He had pitched a proposal for what would become The Devil's Backbone to the Mexican Institute of Film, but they rejected the idea because they thought it was "too big" of a movie. The eventual solution to del Toro's problems arrived courtesy of filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar.Almodóvar, the director of Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, All About My Mother, Talk to Her and many more, had met del Toro and expressed his fondness for del Toro's first film. According to del Toro, Almodóvar said, "I liked your movie Cronos very much, and if you ever come to Spain my brother and I would like to produce a movie for you." In 1997, del Toro "took a chance and wrote to Pedro and said, 'Remember that conversation we had?'"Almodóvar produced Devil's Backbone, but gave del Toro completely control over the film, an experience del Toro says was "like an antidote to Mimic, which was five producers around me at all times." Almodóvar also gave del Toro final cut – another condition that was denied to him on Mimic.

Compromise as an Art Form

The stories about the production of The Devil's Backbone are what primarily make up Matt Zoller Seitz and Simon Abrams' book, but there are frequent side-steps into the process of filmmaking as a whole. In these moments, del Toro's knowledge of film and filmmaking shine brightest.One key passage involves del Toro discussing the very nature of being a director, and how the job itself is perceived by film fans. "Since Erich von Stroheim or Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton or D.W. Griffith, we've enthroned the idea of the autocrat: the director who controls everything," del Toro says before pointing out that it's simply not true. "The reality is that every director knows that it's about saying, 'Oh, this accident happened, and it's better.'"The filmmaker sums it up succinctly: "Directing is compromise as an art form."To further illustrate the point, del Toro turns to one of the most historically obsessive filmmakers in the history of the medium: Stanley Kubrick. Surely an auteur such as Kubrick was in control of everything, right? Not exactly. Del Toro talks about befriending Tom Cruise (the filmmaker wanted Cruise to star in his now-aborted At The Mountains of Madness adaptation) and proceeding to pick the actor's brain about working with Kubrick on Eyes Wide Shut: "I asked him, 'Do you think [Kubrick] controlled everything? Or was he able to create opportunities for accidents?' And [Cruise] said, 'Absolutely, he left room for accidents. In fact, sometimes you had the feeling that he was waiting for that accident to present itself so he could recognize it.'"

Prep Work

Del Toro eloquently recalls almost every tiny detail about the production of The Devil's Backbone, and that includes all the pre-production work. When it comes to designing a film, the filmmaker says he usually takes about six months of prep work:

"I take three months alone with a conceptual illustrator, and I figure out everything before we are joined by the production designer and wardrobe designer. I just do sketches with them. And then for three to five months more, I work with the whole team."

Del Toro's prep work on The Devil's Backbone was slightly shorter than other films, because he had committed to making Blade II.

Chekhov's Bomb

One of the most iconic pieces of imagery from The Devil's Backbone is an unexploded bomb, sticking out of the ground in the courtyard of the orphanage. The bomb is a constant metaphorical reminder of the Spanish Civil War raging beyond the orphanage's walls: "The bomb is omnipresent in the middle of the courtyard much like the war," del Toro says. "It just says, 'The war is here....'" The filmmaker goes on to say that he "wanted [the bomb] to be almost a mother figure to the kids. They planted flowers around it and put ribbons on it, like it's a fertility goddess, a totemic figure. But I wanted it to look over them the whole time."Del Toro's thoughtfulness about the bomb, which is omnipresent but not exactly a key element to the overall story, further illustrates just how much thought he pours into the construction of his films. The bomb is always there, and even when it's not on screen, the audience is subliminally thinking about it. How could they not?"If you have a bomb in your backyard, unexploded...basically it becomes the north of your entire geography," del Toro says. "Whether you sleep close to or far from the bomb, or you cross the bomb to go to the well, it's always there at the center...But even if you live with a bomb, it's still a bomb. That's the essence of a civil war. You live with a conflict and it can become matter-of-fact, everyday, but you're still living with this bomb at home."

In Sequence

The Devil's Backbone editor Luis De La Madrid reveals that, unlike a majority of film productions, Backbone was filmed in sequence: "First of all, the most important thing was that the movie was filmed [in sequence], with respect for continuity. Guillermo laid out the whole movie. The choreography of the characters within the camera got very elaborate, and that creates a significant amount of work for me."The editor goes on to say that the in sequence filming created a wealth of material to work with – too much material, in fact. As a result, some trimming needed to be done: "When we made the first cut, I had to compress the movie a bit because otherwise it would've easily lasted up to two and a half hours."The final cut runs 107 minutes.

No Film Without Images

Cinematographer Guillermo Navarro has amassed an acclaimed career shooting films such as Quentin Tarantino's Jackie Brown and TV shows Hannibal, Narcos, and more. Navarro has worked with del Toro five times: Hellboy, Hellboy II: The Golden Army, Pan's Labyrinth, Pacific Rim, and of course, The Devil's Backbone.In an interview in The Devil's Backbone book, the cinematographer discusses his process, along with his philosophy of cinematography as a whole: "Here is my take on cinematography: there is no film without images, correct? If you can't see it through the lens, it doesn't exist in the movie. If you respect that the camera will tell the story, then the camera now has a role [in the story]...So what I'm calling the exercising of film language is really allowing the cinematography to be the storyteller. Cinematography is a language like any other, with its own grammar and rules. Being fluent in that language requires a strong understanding of cinematography as part of the storytelling process. It's not just people saying things while the camera registers what they say."For his part, del Toro has his own unique interpretation of cinematography. To del Toro, it goes beyond shooting a film – it also encompasses the various elements that go into the overall look of the film as a whole, including costuming and set design: "I think cinematography is not a single discipline...cinematography is set design, wardrobe design, and staging...So when somebody says, 'That cinematography is great,' that person is saying, 'Great set design, great wardrobe design, great staging, great cinematography.' And by the same token, when they say, 'What a great production designer,' they're saying, 'Great cinematography,' etc. These disciplines are inseparable."

The Voice and Soul of the Movie

Some film critics may roll their eyes (and plug their ears) at certain film soundtracks. It seems there's a school of thought regarding movie music that thinks a score should be undetectable; something in the background; something non-manipulative. But here's the thing: film, as an art form, can't help but be manipulative. That's what it does best; that's its power.As a filmmaker and a film viewer, del Toro is averse to the concept of "invisible" soundtracks. "You come out of a Krzysztof Kieslowski film with Zbigniew Preisner's score in your head," he says. "You come out of a [Frederico] Fellini movie with Nino Rota going like a merry-go-round in your head. You come out of Sergio Leone's Westerns whistling Ennio Morricone. So this idea that a score should be invisible is bullshit. You come out of Jaws going 'da-da-da-da,' out of Star Wars, so forth."To del Toro, music is an essential key to a film. He calls it "the voice and soul of the movie," and adds: "I can speak of surface, actors can speak of emotion, but the ultimate varnish of a film is when the music comes in and it feels of a piece by providing you with an insight to the emotions of the film. As if it was an entity."

Think About Your Saddest Memory

The bulk of the cast of The Devil's Backbone is made up of child actors, which can understandably create a tricky situation on a film set. In a matter-of-fact manner, Guillermo del Toro discusses his process for how he directed the Backbone child actors. One thing the filmmaker does is insist that the parents of the child actors do not rehearse lines with their kids. He'd rather the children's performance be found more naturally, and seem less reheased; less like a kid in a TV commercial.Del Toro also wrote out biographies for his young actors to serve as "homework": "What I do with the kids is, in pre-production I create a bio for the character, and I give it to them. I also gave bios to [the adult actors]: 'Here's your bio from birth to the end of your most recent birthday.'...[Then I ask] 'What do you have in common with this character?' That's the first homework we do with the actors. 'What do you like and identify with in him?'"For big emotional moments, del Toro gave his young actors this advice: "You don't have to tell me what it is, but think about your saddest memory. What are you saddest about in your life....And then when we are shooting a scene where the character is sad, he goes there."

“Let’s Kill Him!”

While del Toro's experience with the young actors working on Devil's Backbone was mostly successful, he did have problems with one unnamed actor that the filmmaker labels "a pain in the ass."The young actor was such a problem that del Toro decided to kill his character off in the film. During an emotional scene in the film that reduced del Toro and his crew to tears, the young actor was supposed to be laying perfectly still in the background of the shot, having been killed in an explosion. And then problems arose:

"[W]e're all weeping, everybody, the cameraman is weeping, the script girl is weeping, I'm weeping, and we say, "That's it! Print!" and then the script girl says, "I think there's movement in the background." "What? Can we go back and rewind?" and this dead kid, like a George Romero zombie, gets up and looks at the camera!"

The kid that sat up like a zombie was, of course, the kid del Toro had been having trouble with:

"I go up to this kid, who we are killing because he was a pain in the ass! He was in other scenes and he always ruined the scenes, so I said, 'Let's kill him!' So he dies in the explosion and fucked up the last fucking scene he had! I go up to him and say, "Why the fuck did you do that?" and he said, "Because I feel my character wouldn't die! He would be injured!"

Red Eats Every Color Around It

Guillermo del Toro has made use of several red-colored characters in his films, most notably Hellboy, but also Crimson Peak. During a discussion about the use of color in both The Devil's Backbone and his films in general, the filmmaker details the difficulties in filming a primarily red character:

"[O]ne of the hardest things to do is to use a red character, which I've done a few times, including Hellboy! Red eats everything. Red eats every color around it. And then reds needs to be exactly red...When people see Hellboy and think, Oh, he's just painted red!, there are least twenty shades of red in that! It's incredibly detailed because we need to do the shading, the liver spots. A face is not pink! There's green on it, there's blue on it, there's yellow on it, there's red."

When Matt Zoller Seitz asks del Toro how to solve the problem, del Toro explains:

"You need to use exactly the shade of red, and find a cool color that contains it. Like, there's a [filter] called steel blue. It's a gel that I started to use on Mimic because of the paint job on the insects. We started using it in there and we discovered that it still looked greenish-blue, a very strong cyan, but it contained enough warmth that the red didn't react badly to it. So we needed to use that on the night shoots in Hellboy and then have a very, very soft neutral light following him a little. Otherwise, you have a chocolate bar with an overcoat."

Hitchcock and Buñuel

During the lengthy interview of The Devil's Backbone book, Matt Zoller Seitz points out to del Toro that Alfred Hitchcock and Luis Buñuel seem to be the two primary influences on both The Devil's Backbone and del Toro as a filmmaker.Del Toro agrees, saying "They're the two filmmakers I find most powerful, and they are both interested in cruelty, in the same obsessive, Catholic way. They are both very Catholic. They are both obsessed with sexual hunger, sexual power play, and sexual possession."But while Hitchcock was more repressed and coy about his obsession due to a more sheltered lifestyle, Buñuel was more open and expressive. "[T]he difference," del Toro says, "is you can see that Buñuel lived a lot, and therefore he understood that there was an immense primal force in women. That realization is an elemental force in Buñuel. His men are almost either airheaded Puritans or bumbling sinners. In Hitchcock there is a contemplation of that. I would argue that in Notorious, Hitchcock is as in love with Ingrid Bergman as he is with Cary Grant. He has an admiration for male and female energy that is a lot more sublimated and a lot more perverse, in a way, than Buñuel's."

Late-Period Spielberg

One of my personal favorite parts of the Devil's Backbone book is a section where Guillermo del Toro sings the praises of the late-period films of Steven Spielberg. More often than not, people seem to complain that the later Spielberg films have lost the excitement of his earlier blockbusters, but I personally would argue that Spielberg has only grown better and bolder in the 21st century. So it was pretty refreshing to read that del Toro feels similarly."I have an enormous admiration for late-period Spielberg," the filmmaker says "I love War of the Worlds. I love A.I. I think A.I. becomes more and more painful with every viewing. I find it deeper each time...But I'm obsessively in favor of Catch Me If You Can. That is a complete musical masterpiece. It is symphonic, always iun motion, always elegant. It's sort of a Stanley-Donen-on-steroids type of movie."Del Toro says that part of Spielberg's talent as a filmmaker lies within his humanistic personality: "If you are a humanistic filmmaker–if you are ultimately in favor of individuals–it comes across in your films...I feel Spielberg...is a humanist. He really believes profoundly in American values..."

Therapy

The Devil's Backbone won acclaim when it was released in 2001, and del Toro's career would go on to win even more acclaim with Pan's Labyrinth. But even if these films, and others hadn't been met with a positive critical response, it wouldn't have mattered to del Toro as much as the therapeutic experience of making them."The three movies of mine that are completely therapy for me are Pan's Labyrinth, Devil's Backbone, and Crimson Peak," del Toro says. "And now a fourth, The Shape of Water. Completely, fully, one hundred percent therapy for me. How they played for other people, or whether they played and are seen as beautiful fantasy or this or that. I have no control over. But to me the four movies are parts of my brain interacting within my head."