The Chuck Klosterman Interview Part 2: 30 Rock, Mad Men, The Office, Arrested Development, And Why Movies And TV Have Made Us Less Human

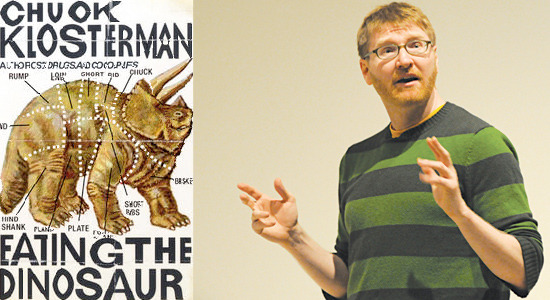

In his new book of essays, Eating the Dinosaur, pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman posits that "as a species we have never been less human than we are right now." Part of the reason why this has happened, he says, is that our growing consumption of media, movies, and entertainment has made it so that "we can't really differentiate between real and unreal images." He concludes that we thus, "no longer have freedom to think whatever we want." For instance, the words, "basketball game," instantly trigger a mental image of the NBA before (rather than?) a memory of a real experience. The Klosterman twist is that while "reading about Animal Collective on the Internet has replaced being alive," he's generally okay with this cultural and social development. I should add that he admits that the Unabomber's Manifesto and its author had several really good and scarily prescient points.

In his second interview with /Film, many of Eating the Dinosaur's ideas are discussed within the context of modern television series like Mad Men and 30 Rock. We also discuss the significance of the odd documentary-style used on The Office and now Modern Family, and why he believes pop-culture writing/blogging on the internet unfortunately has become "an institutional voice" that rivals academia. Is this where I type, "Hopefully the next trailer is better?" For our first interview round with Chuck Klosterman, click here. For Klosterman's updates on film adaptations of his books Fargo Rock City and Killing Yourself to Live, click here.

Hunter Stephenson: What's your biggest problem with 30 Rock?Chuck Klosterman: [pause] Does it seem like I have one?Chuck Klosterman: Oh. It's just a question. [laughs] I guess the fact that—30 Rock is the best written show on television, I think, at least among comedies—but the thing that I don't like, I guess, and this is a weird thing to say, are the people who like it too much. [laughs] And people who feel this desire to associate themselves with it—it's probably the same problem I have with The Daily Show. I don't like people who look at these shows as, not so much brilliant artistically, but brilliant philosophically. And they want to show people that something about these shows defines who they are.

To me, it's not that different from people who make a big production of really liking a reactionary comment. See, I don't want to say anything bad about 30 Rock. But as a critic I would also say that [the show] probably confirms a lot of negative perceptions that people have of the New York media. It almost seems like they're mocking that confirmation, but that's not what is happening.

Have you considered that Kenneth the Page on 30 Rock is comparable to the New Blackface on TV?Chuck Klosterman: Oh? [laughs]In that the character is a grotesque stereotype of Southerners. One who: has eaten squirrels, stutters, gets sexually overheated in public, is incredibly naïve as to be a source of helpless amusement to rich whites, is religious as to invite trickery, and is subservient, particularly in his relationship with Tracy Jordan?Chuck Klosterman: You know, what will be interesting is, like, in 25 years will it be impossible to make jokes about Southern people? I don't know. Right now, there are certain groups that you can totally make jokes about on mainstream television: the South, people who are really Christian...there are other ones. [Note: This interview was conducted prior to the ongoing Italian-American controversy surrounding MTV's Jersey Shore.]But the caricature of a Southerner is the most ubiquitous and accepted on television...Chuck Klosterman: Well, yeah, probably. I mean, The Simpsons has a character like that. I think part of that is, well, the kind of people who would be offended by that—a person from the South—is less offended by everything. In other words, there needs to always be [pause] you know, anytime a minority is made fun of or wronged in public, there needs to be a voice from that minority saying "This is wrong." I don't see that as much from people in the South, because they seem...I'm generalizing. I don't know how to describe it, I guess.

Have you considered that Kenneth the Page on 30 Rock is comparable to the New Blackface on TV?Chuck Klosterman: Oh? [laughs]In that the character is a grotesque stereotype of Southerners. One who: has eaten squirrels, stutters, gets sexually overheated in public, is incredibly naïve as to be a source of helpless amusement to rich whites, is religious as to invite trickery, and is subservient, particularly in his relationship with Tracy Jordan?Chuck Klosterman: You know, what will be interesting is, like, in 25 years will it be impossible to make jokes about Southern people? I don't know. Right now, there are certain groups that you can totally make jokes about on mainstream television: the South, people who are really Christian...there are other ones. [Note: This interview was conducted prior to the ongoing Italian-American controversy surrounding MTV's Jersey Shore.]But the caricature of a Southerner is the most ubiquitous and accepted on television...Chuck Klosterman: Well, yeah, probably. I mean, The Simpsons has a character like that. I think part of that is, well, the kind of people who would be offended by that—a person from the South—is less offended by everything. In other words, there needs to always be [pause] you know, anytime a minority is made fun of or wronged in public, there needs to be a voice from that minority saying "This is wrong." I don't see that as much from people in the South, because they seem...I'm generalizing. I don't know how to describe it, I guess.

From the little I've experienced, it seems part of Southern culture is to sort of not get too upset by that kind of stuff, not to take it too seriously. Like, Larry the Cable Guy, well, he's from Nebraska, but he projects himself as a Southern stereotype on purpose, but no one is really in that position to be like that is very offensive. If you sort of associate yourself by saying—I'm using the wrong words here—if you sort of identify yourself as the kind of person who thinks that political correctness has gone too far, you can't say "Well, in this case it's gone too far."

I guess no matter how naïve they make [Kenneth the Page] seem, or what a simpleton, he's always portrayed as the better person, or the only really good person there, or the only sincere person in New York. You can kind of make fun of anybody as long as they always win in the end. He always ends up being happier than every other person on the show, except for Tracy Morgan's character. But [Tracy Morgan's character] is the same kind of thing, he plays a stereotype, but in the end he's one of the most likable characters.

I've compared the two characters on this level, but I believe Tracy Morgan is playing a "stereotype" of himself, and Jack McBrayer's character is different. There's more to say, but moving on. In the book, you say that one of the unasked questions about The Office [U.S.] is the camera. I'm wondering if you can extend on that...Chuck Klosterman: The idea of the mockumentary, with This is Spinal Tap or anything like this: What's interesting about The Office, and it's really to the credit of the British version, because that's who started the idea, is the idea of "Has anybody thought of using non-fiction film as just the static way of showing narrative?" And it's never ever explained why these people are being filmed or why their actions are. What would be the purpose, you know? There is a new show that's already out on ABC about this family where it's like, the guy who played Al Bundy is in it, Ed O'Neill, and they are filming it in the same kind of fashion as The Office. [Ed. Note: Modern Family] And somebody asked me why they were doing this. And also, what are this show and The Office trying to say about their characters that other shows are not? And the fact is, [Modern Family] is just doing it because The Office is successful. This style is now becoming the normative way for audiences to watch television.

I've compared the two characters on this level, but I believe Tracy Morgan is playing a "stereotype" of himself, and Jack McBrayer's character is different. There's more to say, but moving on. In the book, you say that one of the unasked questions about The Office [U.S.] is the camera. I'm wondering if you can extend on that...Chuck Klosterman: The idea of the mockumentary, with This is Spinal Tap or anything like this: What's interesting about The Office, and it's really to the credit of the British version, because that's who started the idea, is the idea of "Has anybody thought of using non-fiction film as just the static way of showing narrative?" And it's never ever explained why these people are being filmed or why their actions are. What would be the purpose, you know? There is a new show that's already out on ABC about this family where it's like, the guy who played Al Bundy is in it, Ed O'Neill, and they are filming it in the same kind of fashion as The Office. [Ed. Note: Modern Family] And somebody asked me why they were doing this. And also, what are this show and The Office trying to say about their characters that other shows are not? And the fact is, [Modern Family] is just doing it because The Office is successful. This style is now becoming the normative way for audiences to watch television.

But one of the reasons why The Office is successful, though, is because what is the difference between TV and film? The main difference is that film is based around story, and TV is based around characters. So, it doesn't really matter what the script of a television show is nearly as much as how much the audience likes the characters. But how do you make the characters likable and relatable, which has always been the core [concern] in TV writing? In a show like The Office, they realized, "If we make it as a documentary, we can have Jim talk to the camera and Pam talk to the camera."

And that's why I even think the minor characters in The Office seem much rounder than, say, a minor character in Barney Miller, where we'd only see glimpses of interaction. The Oscar character on The Office is able to emote directly into the camera, and I think because of that, it's the same reason why documentaries work. There is nothing that can persuade you or change the way you think more than someone talking at you and being themselves; seeing someone talking off-the-cuff in a way that says, "This is who I am."

This is funny, because I've had conversations about the camera with several people. And I'm usually the only one who views the camera as a character. But I also view the camera, and the people who are there filming that we never see and the people who are "producing" [the documentary], as possibly having a devious agenda. In my mind, they are filming this because this particular office represents a last look at a definitive office culture, maybe. They are documenting a depressing social experiment on the way out. And it's eerie also, because filming will go on forever, or as long as this Dunder-Mifflin branch is around.Chuck Klosterman: And not just forever, but they go outside of the office, and follow these people home or follow them to a party. In the book, you dedicate a chapter to the absurdity of the laugh track on television. And you reach some rather dark conclusions about the societal side effects the laugh track has had on all of us. (Excerpt included below.)

In the book, you dedicate a chapter to the absurdity of the laugh track on television. And you reach some rather dark conclusions about the societal side effects the laugh track has had on all of us. (Excerpt included below.)

"In the short term, [the laugh track] confirms that the TV program we're watching is intended to be funny and can be experienced with low stakes. It takes away the unconscious pressure of understanding context and tells the audience when they should be amused. But because everything is laughed at in the same way (regardless of value) and because we all watch TV with the recognition that this is mass entertainment, it makes it harder to deduce what we think is independently funny. As a result, Americans of all social classes compensate by living like bipedal Laff Boxes: We mechanically laugh at everything, just to show that we know what's supposed to be happening. We get the joke, even if there is no joke."

What is the difference, in your opinion, between hearing a laugh track and hearing claps at a tennis or golf match on television? Is the latter not also a form of conditioning that creates comfortability and familiarity in viewing?Chuck Klosterman: But it would be different though if you watched a tennis match with no audience and they piped in people clapping. I mean, sporting events and watching a stand-up comedian, and hearing people laughing or clapping, these are real organic things that are actually happening.But what is the difference between a laugh track and going to see or watching The Late Show with David Letterman, where lights tell people when to laugh and applaud?Chuck Klosterman: When people go to David Letterman, that's totally true. They are acting [pause] like a laugh track. And even live studio audiences for a show like Happy Days, those people were basically there to be the machine. What's different about a tennis match or a stand-up comedian, sure people go through certain interludes where they are supposed to clap, but there are also moments when their reaction is uncontrolled. If, say you watch when Monica Seles got stabbed playing tennis, [laughs] the reaction of that crowd was not like a conditioned response.

I think when we saw David Letterman personally come forward on his show and say he was having these sexual affairs, and that this guy was blackmailing him and the affairs were true, it was a very interesting three second moment in television because the audience could clearly not tell if it was real or false. You kind of saw that moment of reality, and that's what you're always looking for.

Somebody was just talking to me recently about the show Survivor, and one of things I really like about Survivor is that at the end of the show, when somebody gets voted off, they really have been blindsided. They authentically thought that they knew what was going on, and it turns out they didn't. They have been betrayed and you see their face, and it's impossible to fake, it doesn't look like television. You know. Meryl Streep cannot be as shocked as someone who is shocked for real. And that to me is the difference between a live audience and a laugh track.

[laughs] Okay. Do you see Beavis and Butt-Head as the first show to subvert the medium's use of a laugh track? In that, while there's no laugh track, the characters' laughter almost serves as one because what they are laughing at is usually not funny. But their laughter makes us laugh...Chuck Klosterman: That's actually a very interesting way of thinking about it. I had never thought of that. The thing with Beavis and Butt-Head to me, I think that people in the media—people who were rock critics—had always realized that they wrote about whether or not, like, the new Def Leppard was good. And then the consumers had their own opinion.

It was interesting because that show was illustrating how a large segment of the audience perceived music like this, and that the things they think are cool and the things they think suck are very emotive and it has nothing to do with some preexisting knowledge of the artist, or the canon of rock, or what genres are supposedly good and what genres are supposedly bad. It was sort of like, "This is how the music is actually consumed."

And I really feel after Beavis and Butt-Head, you started to see [an effect] in people writing about rock. The initial rock writing, the Lester Bangs stuff, it was very visceral with closer ties to, sort of, traditional art criticism. And then rock writing became very intellectualized, to the point where most people writing about music were doing it from almost a purely academic perspective. It was very jarring to see this happen.

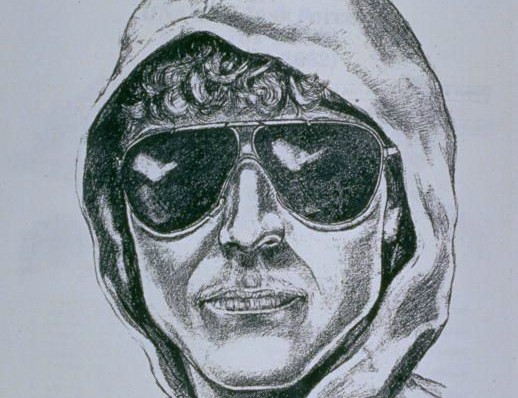

Would you agree that there is a defeatist perspective running throughout Eating the Dinosaur?Chuck Klosterman: Hmmm. [pause]The last chapter is entitled, "FAIL," and focuses on why parts of the Unabomber's Manifesto might turn out to be right. And another big topic in the book is the ubiquity of advertising and, well, the "evolution" of advertising on television. You basically say that the illusion is complete, that we are complicit in the illusion and that we want to be complicit in it.Chuck Klosterman: Yeah. One of the ideas in that book, it's not that media is everywhere, because everyone already knows that. The larger idea is that media is everywhere and it's so intrusive and it's so central to every experience we now have that sometimes we don't even notice that it's there. Right? We don't even realize that the way we feel about things that we view as being personally important are actually part of the collective media. So, when you say "defeatist," maybe. But is it defeatist or acceptance?Well, the conclusion the book reaches about media, life and culture is basically, instead of throwing up your hands at what it's become, you're saying "blow my hands off."Chuck Klosterman: I realize I am not able to control what I think about. And it was a hard thing to admit. And I think most people don't. But no one does [control what they think about]. At this point, it is impossible...the idea that we have a real freedom of thought. I think that anyone who is involved with the culture at large does not have freedom of thought. You know? So, I think that you have to first accept that your understanding of the world and my understanding of the world, is to a degree decided; but once you accept that realization, I think you can have more interesting thoughts inside that seemingly defeatist perspective. Um, I think when I wrote Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs (2003), I think my big thing was that a lot of consumer culture is very interesting, and that you can think about these things in the same way you think about high art and it doesn't really matter...

Would you agree that there is a defeatist perspective running throughout Eating the Dinosaur?Chuck Klosterman: Hmmm. [pause]The last chapter is entitled, "FAIL," and focuses on why parts of the Unabomber's Manifesto might turn out to be right. And another big topic in the book is the ubiquity of advertising and, well, the "evolution" of advertising on television. You basically say that the illusion is complete, that we are complicit in the illusion and that we want to be complicit in it.Chuck Klosterman: Yeah. One of the ideas in that book, it's not that media is everywhere, because everyone already knows that. The larger idea is that media is everywhere and it's so intrusive and it's so central to every experience we now have that sometimes we don't even notice that it's there. Right? We don't even realize that the way we feel about things that we view as being personally important are actually part of the collective media. So, when you say "defeatist," maybe. But is it defeatist or acceptance?Well, the conclusion the book reaches about media, life and culture is basically, instead of throwing up your hands at what it's become, you're saying "blow my hands off."Chuck Klosterman: I realize I am not able to control what I think about. And it was a hard thing to admit. And I think most people don't. But no one does [control what they think about]. At this point, it is impossible...the idea that we have a real freedom of thought. I think that anyone who is involved with the culture at large does not have freedom of thought. You know? So, I think that you have to first accept that your understanding of the world and my understanding of the world, is to a degree decided; but once you accept that realization, I think you can have more interesting thoughts inside that seemingly defeatist perspective. Um, I think when I wrote Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs (2003), I think my big thing was that a lot of consumer culture is very interesting, and that you can think about these things in the same way you think about high art and it doesn't really matter... And, with respect, you were probably the first one to do that, or to do it at such a high profile level, I think.Chuck Klosterman: Well, I think I had very good timing and I think the timing was probably, everyone would like to admit that what they did was somehow their own genius or a reflection of their writing. I realize the main thing was that there was a lot of interest in those ideas and no one had sort of done it yet. It was before the internet had sort of exploded, and then when it did, a lot of the ideas in Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs were sort of adopted by the institutional form of the internet.

And, with respect, you were probably the first one to do that, or to do it at such a high profile level, I think.Chuck Klosterman: Well, I think I had very good timing and I think the timing was probably, everyone would like to admit that what they did was somehow their own genius or a reflection of their writing. I realize the main thing was that there was a lot of interest in those ideas and no one had sort of done it yet. It was before the internet had sort of exploded, and then when it did, a lot of the ideas in Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs were sort of adopted by the institutional form of the internet.

But, returning to what I was saying, my interest in culture in Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs was more from the outside, where I was sitting in this apartment in Akron, Ohio consuming culture and thinking about it. And then by a whole collection of events, most notably the publication of that book, my perspective kind of changed, now I was more on the inside. So, I still felt like somebody who was just watching it, but now I had a better sense of what was really going on. And I started to spend a lot of time thinking about, "Why is this show making me feel this way?"

Did you start to feel more manipulated by the stuff you were consuming?Chuck Klosterman: Oh, no. I'm less manipulated now. I was more manipulated then, it's just that I wasn't as aware of it as I am now. Once you become aware of that manipulation, it's easier to separate yourself from it. So, I mean, while this book probably does seem more defeatist than Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs...Would you agree that Eating the Dinosaur is easily the darkest of your non-fiction books?Chuck Klosterman: [makes a sound that possibly conveys profound semi-disagreement]Really. That's how I saw it.Chuck Klosterman: Maybe. Maybe. I feel that Killing Yourself to Live is kind of dark as well, but that was also different because even though it was non-fiction it was narrative, so...I feel like you're looking far deeper into the future with this book than in Cocoa Puffs [and IV]. No?Chuck Klosterman: Well, I dunno. I dunno. That's a good question. I mean, that book is just how I've been thinking about the world for the past year. And now it's weird writing that book, because now that book exists forever. So, now if I feel differently in two years, I might go back and feel really weird [laughs] about my perspective on life at the time I was writing it. But that's happened with every book I've written. Every book I've written feels strange to me in retrospect, which is why I never read anything I've written. I never go back and read my books because it only upsets me. I am a fan of Mad Men and it was great to read your take on it. But did you not feel a need to go into the topic of integrated advertising within Mad Men?Chuck Klosterman: That's interesting. A lot of people have asked me about that.On the topic of advertising, you say, "I enjoy Don Draper. He's got a lot of quality suits. But I'm afraid I might be his employer, and I don't even know it." But while you don't talk about it, that statement is arguably true as it pertains to watching Mad Men. Some have wondered if the show was greenlit partially because it's about advertising and thus it's easier to integrate advertising...Chuck Klosterman: Well, what's also different about a show like Mad Men is that the use of product placement actually increases the degree of realism. Like, it became more real because [Don Draper's] dealing with London Fog than if they made up a company. That's always the thing, people hate the idea of product placement, it drives them nuts. Right? But if it turned out that in a Jonathan Lethem novel that a character consistently drank [a name brand soda] all the way through the book; and later, people had found out that Lethem had been paid money to do this, people would be outraged. Right? They would be shocked.

I am a fan of Mad Men and it was great to read your take on it. But did you not feel a need to go into the topic of integrated advertising within Mad Men?Chuck Klosterman: That's interesting. A lot of people have asked me about that.On the topic of advertising, you say, "I enjoy Don Draper. He's got a lot of quality suits. But I'm afraid I might be his employer, and I don't even know it." But while you don't talk about it, that statement is arguably true as it pertains to watching Mad Men. Some have wondered if the show was greenlit partially because it's about advertising and thus it's easier to integrate advertising...Chuck Klosterman: Well, what's also different about a show like Mad Men is that the use of product placement actually increases the degree of realism. Like, it became more real because [Don Draper's] dealing with London Fog than if they made up a company. That's always the thing, people hate the idea of product placement, it drives them nuts. Right? But if it turned out that in a Jonathan Lethem novel that a character consistently drank [a name brand soda] all the way through the book; and later, people had found out that Lethem had been paid money to do this, people would be outraged. Right? They would be shocked.

I remember there was a situation last year, where a few writers—I can't remember all of them, one of them was the girl who wrote [inaudible]—they got together and wrote a book for a car company. And people were very uncomfortable with that. And yet, if you write a novel you want the characters to have a specific interest in a real thing. [laughs] It would seem weird if in a novel the character always drank 'Cola,' and that's all they ever said...

Nothing defeats the suspension of disbelief for me more than seeing a character in a movie go into a bar and order a beer. No one ever does that. No one ever sits down at a bar and says, "Give me a beer." They say what kind of beer they want. So, in a strange way, product placement is philosophically problematic because it seems less like art, but for the consumer it actually makes it seem more real, you know?

Right. And 30 Rock has done the opposite of Mad Men in this regard, where it shoves the advertising in your face. But recently Tina Fey said some of it was [integrated placement] and some of it wasn't. But there is a big difference between how Mad Men does this and 30 Rock and SNL do it, I think.Chuck Klosterman: But in the way 30 Rock does it, you can tell that this is an ideological problem for Tina Fey. [Note: I disagree.] So, what she is always saying to herself is, "If I'm always to a point of recognizing this, then we really can't be criticized for it, because we make a big deal about it." And it, you know, erodes, any possibility that anyone can say she's a sell-out or whatever. I once wrote about Arrested Development when it was going off the air, and they were running out of money, and my thing was, "You know, what they should do is have every character wear a [name brand soda] t-shirt all the time. And they should drink [name brand soda] constantly," because they could have gotten away with it.

It would have seemed funny. It would have been the exact same show, but they would always have those shirts on. And [the soda company] would have paid millions and millions of dollars for that, simply for the amount of attention the show would have gotten for doing it. But nobody wants to see that, simply because it changes the artistic integrity.

I remember when Jack White wrote a jingle for [a soda company]. I don't know if it ever became a commercial, but he wrote a very nice song for them. And his argument was, "It would be one thing if we used a White Stripes song. Because I would be selling that song and repositioning its meaning, compared to if I just write a song for [the soda company]." And that does seem different to me.

For example, in Killing Yourself to Live, I drink [a name brand soda] throughout that book. Now, if [that company] came to me now, and said we want to pay you money retrospectively for this, I would be like, "Sure." Why wouldn't I do that? But if they came to me and said, "We'll pay you $25,000 to prominently mention [our soda] in your next book," I would never do it. Now, what's the difference? The only difference is the motive of the artist, but motive matters. It would be weird to me to do that even though it would be the exact same book, because...

I'm curious. When you talk about the topic of TV advertising in the book, you say you flip between channels for sporting events during commercials. But you don't mention how much advertising is actually embedded in the games themselves: from blimps, to dancing holograms, to signs on the field.Chuck Klosterman: That is totally true. I have to admit that I will never know, I guess, because the only thing people seem to know about advertising is that it works. Even though I think that is a flawed argument. But I don't know if that kind of advertising [in games], I don't know how effective that is, because as you bring it up to me right now, it's hard for me to see images in my mind. Like, the [tortilla chip] Fiesta Bowl, I know that they—well, I don't know if they still are, but for a long time they did—sponsored a bowl game, and that they could afford to do so. But I don't know that it changes my opinion about their product at all. Particularly when they sponsor something kind of neutral, like a game itself.

If they sponsored a team, like I grew up loving the Boston Celtics and the Dallas Cowboys. If when I was younger the Dallas Cowboys had been sponsored by [candy company] then I would have been more prone to eat [their candy]. But, I don't know...

Maybe in the future a fast food company will buy a team and incorporate their logo into the team's name...Chuck Klosterman: Yeah, it's a confusing thing. I mean...Yeah.Right. And I bring this up because the line about how you might be Don Draper's employer and you don't even know it: First of all, that's Philip K. Dickian. But also you wonder in the chapter if a sublimination exists in advertising now. You reach a conclusion where you don't even know how a product got into your brain...Chuck Klosterman: Well, yeah. I do think Mad Men, one of things it has inadvertently done, or maybe totally consciously, it has made people feel more positive about the concept of advertising being an art; because someone like Don Draper, he seems more like an artist than a businessman. I mean, he's very cold and calculating, but he also has this mind that seems to work in an artistic capacity. And I think what that does, when people start to have a positive view of advertising, they start reading things into commercials that may not even be there. And we mentioned football ads. This is a prime example: after the Super Bowl, I will go on blogs and I will read people talking about how certain commercials are successful or failures based on how well they are reflecting the temperature of our culture, or where the world is at. And that to me is what I mean when I say people are working for Don Draper and they don't even know it. They are making advertising an art, even though all it's trying to do is make them buy products. Would you agree that over the years movies and television have made the act of "contemplating living" scarier or seem unnatural?Chuck Klosterman: Well, I don't think it's made daily living seem scarier or unnatural; well, maybe unnatural. It certainly has given people or galvanized the belief that a normal life is not enough. And that a good life needs to be completely spontaneous and a romantic experience. And, you know, that's not just Hollywood, that's all media. And, you know, I love the media, I live in the media, I consume this stuff constantly, as soon as I get off the phone with you I'll probably start watching TV. But I know that it's a negative thing and that it's having a negative effect on mankind, because it's changing peoples' view of what "being alive" means.

Would you agree that over the years movies and television have made the act of "contemplating living" scarier or seem unnatural?Chuck Klosterman: Well, I don't think it's made daily living seem scarier or unnatural; well, maybe unnatural. It certainly has given people or galvanized the belief that a normal life is not enough. And that a good life needs to be completely spontaneous and a romantic experience. And, you know, that's not just Hollywood, that's all media. And, you know, I love the media, I live in the media, I consume this stuff constantly, as soon as I get off the phone with you I'll probably start watching TV. But I know that it's a negative thing and that it's having a negative effect on mankind, because it's changing peoples' view of what "being alive" means.

The real conclusion of the book is that we've never been less human than we are now; but that statement could have been said in 1920 and that would have been true, and it probably could have been said in 1680 and it would have been true. I mean, evolution is always happening, right, and the evolution of humankind is a way for us to be less human. And it's weird to think about that; but I'm thankful for that in a lot of ways because it makes my life more comfortable and more interesting. It's weird though to think that the trajectory of people is to not be people. [laughs]

Over the years, I've developed this notion and your books have inspired it, that perhaps the idea of rebellious or nihilistic power through making rock 'n' roll has now been usurped by the consumption of media and entertainment. Rock 'n' roll was hip because it was a very self-destructive force. But has consuming media usurped that, in that where it used to be cool to Kill Yourself to Live it's now cool to Kill Yourself to Not Live? Rather than creating and experiencing, is consuming now preferred in this regard?Chuck Klosterman: What you're saying is a pretty sweeping statement but it might not be wrong. I mean, the reason that rock music and particularly the rock 'n' roll lifestyle became interesting and desirable to people is because it was a different way to live. The rules were different, the experiences were different. People felt as though, because of where they lived, or what their social class was, that they were destined to have a certain kind of life. And rock said, well, you can make up your own life, you know? And that's sort of what the internet does as well. It says that you don't even have to live in this world. But at least rock was limited by the world itself, you know? You can only play music in "the world." But the internet creates a cyberworld. It's a limitless world, where you can become a totally different person, you can associate only with who you want to associate with.

People talk about how judgmental the internet is with blogs and commentators, but it's actually less judgmental than the world at large. In the world at large, I'm sitting at this restaurant, I can't control what people think of me when they look at me. I can't be a better looking guy. But on the internet I can, I can be whatever person I want to be, or I can just totally subtract those issues from the equation. So, I supposed what you are saying is true. Yeah.

Wow. Yeah. I didn't expect that answer. What do you make about arguments against this as it pertains to narcissism?Chuck Klosterman: Yeah, well, everyone says that, it's an easy complaint to make. But maybe the only difference is that the technology didn't exist before. What's a narcissistic person? It's somebody who is not consumed with themselves but consumed with their image. And sometimes I look at the internet, and I think goddamit, I can't believe this is how people are. I can't believe what the world is like. But other times I think this is how the world always was, we just didn't know before.

And when you look at all the insane shit that's on the internet, all of the porn, it makes you think that someone just had to invent that now for the internet. But it was probably always there. The idea, the caricature of the unhappy blogger who just sits around and attacks celebrities—20 years ago he would have worked at a comic book store. Or worked at a record store. I used to go to a record store in Ohio and I remember one guy there used to always tell me how Jimmy Page was a really sloppy guitar player, and the fact that whenever he played live, especially the song "Rock and Roll" from The Song Remains the Same, he would always comment on how sloppy his playing is. [laughs] And now that guy would write that, he would have a blog somewhere called, "Jimmy Page Sucks," or whatever. But he was always there.

The biggest question about the generation of people now—people between the ages of 15 and 30—will they become a totally different kind of person and will society always be different due to the way the internet has changed them? Or is the internet just the first time we've really been able to see what society is? And to be honest, I've never thought about any of this until just now. [laughs] [laughs]

As a culture writer and a critic, how would your rise to prominence and how would your writing have differed if you had commentators commenting on every piece you ever wrote?Chuck Klosterman: Well, to be honest, and I hate to say this, but I do feel that if [commenting] had happened when I was younger that A) I would have definitely been involved with it and B) it would have had a very negative effect on my work. I think it's absolutely impossible not to be affected by commentator culture if you are the original writer of the original post. I see it a lot. I read a lot of sports blogs, and the commentator culture on them is very negative, it's detrimental.

There was a long period of time where you would write and you would put your stuff out in public; and you would never be certain how many people were seeing it and how they felt about it. It was still almost an interior process. So, you made decisions based on your own sense of the world. With the commentator culture, what ends up happening is that it doesn't really matter if people respond negatively or positively, you just get this really central sense of what your audience wants to hear about. I believe that leads people to write about the same things over and over again.

So, this whole idea that the internet was giving us this unlimited freedom and this unlimited number of voices that had a chance to be heard after being frozen out of the media for so long, the strange thing that has happened: there is more of an institutional voice on the internet—it sort of naturally happened—even more than there is in academia. And I think that what's it doing is it's creating people who write about the same things over and over because those things perpetuate response and hits.

Here's a hypothetical question, based on several people you discuss in your book. Let's say you have creative carte blanche and you have to oversee a biopic about one of the following people: David Koresh, Kurt Cobain, or Ted Kaczynski. You get to choose any living director. Which person and director do you choose?Chuck Klosterman: Well, you know Gus Van Sant sort of made a biopic of Kurt Cobain, everybody hated [Last Days], but I kind of liked it. There was one scene I really liked when he's in the house and he's putting music together and the camera moves back. I think that a Ted Kaczynski documentary would be incredible in the hands of the right person. I'm trying to think of who that person would be. I think a Unabomber biopic directed by Werner Herzog would be incredible. David Koresh could be really good too. P.T. Anderson doing a Koresh movie would be interesting. If I had to see a Kurt Cobain biopic, it's hard to imagine it being good to be totally honest. It's too recent. I guess it would be cool if someone took my essay [from Eating the Dinosaur] and made a duel biopic about the last days of Cobain recording In Utero and the David Koresh situation in Waco. And it would be directed by P.T. Anderson, that would be great. Plus, I would be a millionaire. [laughs]Hunter Stephenson can be reached at h.attila/gmail and on Twitter.

Here's a hypothetical question, based on several people you discuss in your book. Let's say you have creative carte blanche and you have to oversee a biopic about one of the following people: David Koresh, Kurt Cobain, or Ted Kaczynski. You get to choose any living director. Which person and director do you choose?Chuck Klosterman: Well, you know Gus Van Sant sort of made a biopic of Kurt Cobain, everybody hated [Last Days], but I kind of liked it. There was one scene I really liked when he's in the house and he's putting music together and the camera moves back. I think that a Ted Kaczynski documentary would be incredible in the hands of the right person. I'm trying to think of who that person would be. I think a Unabomber biopic directed by Werner Herzog would be incredible. David Koresh could be really good too. P.T. Anderson doing a Koresh movie would be interesting. If I had to see a Kurt Cobain biopic, it's hard to imagine it being good to be totally honest. It's too recent. I guess it would be cool if someone took my essay [from Eating the Dinosaur] and made a duel biopic about the last days of Cobain recording In Utero and the David Koresh situation in Waco. And it would be directed by P.T. Anderson, that would be great. Plus, I would be a millionaire. [laughs]Hunter Stephenson can be reached at h.attila/gmail and on Twitter.