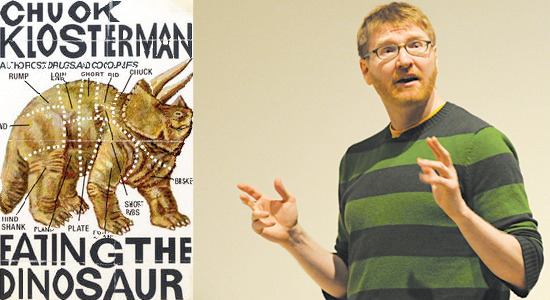

The Chuck Klosterman Interview Part 1: Eating The Dinosaur, The State Of Entertainment Journalism, And Whether Or Not Avatar Is Geekdom's Chinese Democracy

Any pop culture writer today worth a scan online has a unique opinion on Chuck Klosterman. The renown American author and journalist made a name for himself in the aughts with witty, hyper-informed contributions as a former senior writer and columnist at SPIN. In 2003, he released a bestselling book of essays about "low culture" under the title, Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs, that dissected, exploded, and—in the case of Saved By the Bell—meta-ized topics ranging from internet porn to why there's only "one important question a culturally significant film can still ask: What is reality?" To readers with an eye on the future, Klosterman signaled not only the arrival of an adored critic amongst hipsters, TV junkies, and geeks; he was the aware embodiment of the modern intellectual turned as voracious consumer of entertainment. And ever since many a beer has been consumed by writers arguing over or coveting this appointment.

Post-Cocoa Puffs, Klosterman's bibliography has grown to include several works of non-fiction as well as last year's Downtown Owl, a well-received debut novel benefiting from word-of-mouth, not unlike how Puffs did (but with Tweets on top). His latest book, Eating the Dinosaur, is a characteristic essay collection that can be burned through in a night but also raises several troubling philosophical questions. In the first part of Klosterman's interview with /Film, he elaborates on the role feted director Errol Morris played in a few of Dinosaur's themes. We also discuss his opinion of movie junkets, the accelerated culture of movie blogs, and the film most comparable to Guns N' Roses' Chinese Democracy. For the second round of the interview, click here.

Hunter Stephenson: Hi Chuck. So, are you in California to speak about the book?Chuck Klosterman: I'm doing The Jim Rome Show on ESPN, and it's in Huntington Beach, California. And I gotta say, it's creepy as fuck out here man.Chuck Klosterman: There's all of this ocean fog. It's just like The Lost Boys. It doesn't seem like Los Angeles—not that Los Angeles is awesome—but it just seems like a very different place. You know? I feel like I'm at risk.It's like John Carpenter's The Fog out there. Watch your back. The first question is an obvious one. You start off Eating the Dinosaur with an examination of why people do interviews and namely, why you do them. What made you consult Errol Morris on the topic and include his thoughts at start alongside yours? And what do you think Morris has contributed to film as far as truth?Chuck Klosterman: Well, I kind of thought that Errol Morris's film about Abu Ghraib really fit specifically into this idea, because Standard Operating Procedure, there is very often a bunch of people being interviewed who, as far as I can tell, have absolutely no logical, positive reason for talking about their involvement. You can say, "Well, they wanted to say what their side is," but there is no way that anyone will watch those people and—while they may find them empathetic—it's not going to excuse anything they do. All it's going to do is further illustrate the reality of that situation.

And Morris has done a lot of work in his career like that—he had that show First Person on IFC about unfamous people who inevitably came across as really fascinating but really strange. I was also really curious why I was responding to questions when I was interviewed. And it sort of dawned on me that I had always interviewed people as a journalist because I was personally interested in what they were saying. It never occurred to me to think about what they were getting from the experience.

And then, when it started to happen to me when I was being interviewed, I realized that I still could not answer that question. So, I thought, well, I'm going to talk to people like Errol Morris and [This American Life's] Ira Glass, people who are already perceived by audiences as being experts at the interview process, and ask them what they think people are getting out of it. Morris seemed like an obvious person, and that interview was the only time I had really spoken to him in person. He's a very difficult guy to find, [laughs] which might be different now, because he's on Twitter. But at the time, it was a struggle.

Was Morris familiar with you and your work when you asked him to participate? Your name is pretty established, so I'm curious if that changes the dynamic.Chuck Klosterman: I think he was familiar with me after I made the interview request. And then I think he researched me [laughs] until he basically knew everything about me. [laughs] I got the sense that his assistant knew who I was. A younger dude. When I interview somebody, sometimes I do wonder if they have read other interviews I've done. But you can't ask that question, you can't say, "Do you know who I am?" because if they do, it's awkward and if they don't, you look like a complete moron. [laughs] And there's different kinds of fame. Being famous as a writer is not the same as being famous on a sitcom or being famous as somebody in a band. Visual fame is very different from written fame.One aspect that I feel you didn't bring up with the first chapter on the purpose of modern day interviews is: Do you not feel interviews are vital to cultural discourse, and even within the cycle of life, once you reach a certain level of experience and a certain age, should you not share the opinions and realizations you have reached?Chuck Klosterman: That's a good point, and I certainly would have agreed with you totally five or ten years ago. But, as I've now had both sides of that experience and look back at the work I've done as a journalist and what I've tried to do, and when I look back at how I come across when other people have written about me or talked about me—I started to get really nervous about whether the way people are portrayed in this process is remotely accurate.

Was Morris familiar with you and your work when you asked him to participate? Your name is pretty established, so I'm curious if that changes the dynamic.Chuck Klosterman: I think he was familiar with me after I made the interview request. And then I think he researched me [laughs] until he basically knew everything about me. [laughs] I got the sense that his assistant knew who I was. A younger dude. When I interview somebody, sometimes I do wonder if they have read other interviews I've done. But you can't ask that question, you can't say, "Do you know who I am?" because if they do, it's awkward and if they don't, you look like a complete moron. [laughs] And there's different kinds of fame. Being famous as a writer is not the same as being famous on a sitcom or being famous as somebody in a band. Visual fame is very different from written fame.One aspect that I feel you didn't bring up with the first chapter on the purpose of modern day interviews is: Do you not feel interviews are vital to cultural discourse, and even within the cycle of life, once you reach a certain level of experience and a certain age, should you not share the opinions and realizations you have reached?Chuck Klosterman: That's a good point, and I certainly would have agreed with you totally five or ten years ago. But, as I've now had both sides of that experience and look back at the work I've done as a journalist and what I've tried to do, and when I look back at how I come across when other people have written about me or talked about me—I started to get really nervous about whether the way people are portrayed in this process is remotely accurate.

I don't expect it to be perfectly accurate, but sometimes I feel now that it might actually have the opposite effect of its intentions. So, I started wondering if there is this inherent problem with trying to illustrate the reality of someone through the interview process, is that ultimately bad for discourse? In other words, are we actually making people more confused about the art they consume? When I was interviewing, say, Bono or whatever, I was hoping that I would illustrate this guy in a way that would make people who listen to U2 records have a better or amplified experience with his art. Now, I wonder if it perpetuates the unreality.

You speak to [British culture journalist and biographer] Chris Heath in the book and he believes that celebrities who are required to do a lot of press begin to look at better interviews as an anecdote to express themselves. But do you feel the rise of so many press junkets, "round table" interviews, hundreds of "10-minute" phoners, and online media, does this somehow, even subconsciously, play into the unraveling of celebrity?Chuck Klosterman: I don't think it plays into the unraveling of celebrity, but I think it certainly increases the potential for minor celebrities to seem famous. You know, with the junket situation, I would say junkets are nothing but negative. And it is crazy. The thing is, to be totally honest, most of what I consider "real journalists" would not go to a junket. Sometimes you have no other choice, but junkets are mainly a way for people—I don't want to say that they just want to meet John Travolta—but they're not getting anything important out of it. These situations are more or less signifying that a person has enough access to meet someone who is famous. They are trying to create a degree of credibility. "What makes me different from someone off the street? Well, I can sit in the same room with Harrison Ford, and he answers my question directly, even if that question is completely meaningless."

It was weird to me to sort of realize...I was doing a story on the second Strokes album for SPIN, I was doing a profile of the band for its release. And it became really obvious to me that The Strokes, every member of The Strokes, like, Albert Hammond Jr., [laughs] had conducted more interviews in their career than George Harrison did in the entire time he was in The Beatles. Because there is so much media now and so much of an understanding that part of what making music is—or making movies or television is—is that you conduct all of these little interviews as part of the marketing platform. And the content of the interviews doesn't even matter, it's just the act of doing them.

I could actually see how much and how negatively that had impacted that band. I think it really shortened the potential that The Strokes had. I think that they became so hyper-aware of how media was changing the meaning of their music and constantly constructing this specific perception of them, that they ended up having a very strange and—in some way—a mildly unsuccessful career. Even though they made one great record and a bunch of other really good songs, it already seems like they're over. And I don't think it's their fault in any way. I think it was the way they were positioned by people who weren't them.

But doesn't that return us to my first question? I feel that all of these micro-interviews are beginning to "neutralize" celebrity through exhaustion, and personally, I feel like this coincides with the populism of the internet. I think maybe we subconsciously desire for this to happen. But you don't agree with this?Chuck Klosterman: Not celebrity, but I think it neutralizes "meaning." I think if anything, it's definitely expanded the definition of the word "celebrity" in itself. If you said someone was a celebrity in the 1950s, people had a clear idea of what you meant. Every aspect of a junket is promotional, and essentially advertising—and I'm even including the journalists who go on them. The people from the film are there to promote their movie regardless of what's written about them or how it's presented, just get these faces and these names across the media. The studio is flying the person out there and putting them up, which is guaranteeing that the coverage they get is like an advertisement.How has the internet and online media changed or eradicated the notion of "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon," not so much the game itself, but the idea of degrees of separation from a celebrity?Chuck Klosterman: Yeah well, now the average person is probably fewer degrees from Kevin Bacon, because it's so much easier to be a celebrity now and therefore it's so much easier to know one. I was in New York, and I feel like pretty much everyone I know there, even if they are not conscious of it and especially if you start talking about reality television, they will realize that they know someone who was on a reality program. But those people are still viewed as a celebrity, but it's a different kind of celebrity. But the potential to know someone famous now has really been amplified. Twitter is interesting in that way. I often wonder when I see these new technologies like Twitter, Tumblr, and before that, just straight up blogging, I wonder how I would have reacted if those things had come into prominence when I was younger. I was sort of on the cusp, but I'm kind of one of the last writers who was able to establish this type of position without using the internet in any way.![]() One of the sentences in your book that has really stayed with me in the days since is, "Reading about Animal Collective on the internet has replaced being alive." What do you make of the phenomenon with movies, where people follow each jpeg and plot detail of a cool-looking movie, and yet, judging by the box office, many of these people don't see the movie that is the source of this excitement, perhaps ever?Chuck Klosterman: There is one clear upside to me, in that the internet has created new ways for people to enjoy things, and especially film. It used to be that you could only enjoy a film by going to a theater and watching it in a public setting. And then the VCR and DVD player made it so that you could see a movie in the theater or wait and see it at home. Or you could watch it multiple times at home. And, so, a movie like Mulholland Drive had more value because it was almost designed for someone to watch it a bunch of times. And now, the internet has brought this third level where you can enjoy a film outside of a film itself [laughs].

One of the sentences in your book that has really stayed with me in the days since is, "Reading about Animal Collective on the internet has replaced being alive." What do you make of the phenomenon with movies, where people follow each jpeg and plot detail of a cool-looking movie, and yet, judging by the box office, many of these people don't see the movie that is the source of this excitement, perhaps ever?Chuck Klosterman: There is one clear upside to me, in that the internet has created new ways for people to enjoy things, and especially film. It used to be that you could only enjoy a film by going to a theater and watching it in a public setting. And then the VCR and DVD player made it so that you could see a movie in the theater or wait and see it at home. Or you could watch it multiple times at home. And, so, a movie like Mulholland Drive had more value because it was almost designed for someone to watch it a bunch of times. And now, the internet has brought this third level where you can enjoy a film outside of a film itself [laughs].

I know this group of women who are really into Twilight, both the books and the films. They think it's terrible but they love it, they love talking about it. And when they email back and forth, if one of them says something surprising that gets everyone's ire up, one of the girls will just send a picture of the Jasper character looking surprised. That is a very interesting way to use film. They have incorporated this film almost like a verbalized cog in their conversation. [Me: Right. A film still has become, like, the new smiley.] The person who the internet is bad for is the director who wants to be a director like Stanley Kubrick...but then again with Kubrick and Hitchcock and guys like that, their films lends themselves to being studied frame by frame [on the internet].

But the person it's a burden for is the narrative filmmaker who wants to write films that only work when seen and heard in sequence, where there are elements of plot that are dependent on the audience not knowing what comes next. In terms of the film and television industry and the internet in this regard, what I really do not like are, of course, spoilers. If I don't get to watch Lost on a Thursday night and I can't watch it on Friday because I'm traveling, I feel like it's a full time job avoiding spoilers.

With Avatar for example, the studio has made a big mistake by putting out the trailers and promoting it how they are, because they are building a consensus and perception that it looks more fake than when people had read about it. There was so much information out that it was going to blow peoples' minds and it was going to be, like, the first time a non-human character was going to look photo-realistic, and now that the trailers are out and it doesn't look real in that way, it's going to affect how people experience the movie.

Even with the last Indiana Jones film or the Star Wars prequels, it's pretty hard to have a static one-to-one relationship with any of these franchise films now. If you're the kind of person who is particularly interested in those films or, you know, in the horror genre, and you want to be part of the conversation about film, by entering into the conversation it now takes away from some of your future enjoyment.

Have you considered that Avatar may be the new Chinese Democracy? Obviously, this question is inspired by your amazing fake review from 2006 of Chinese Democracy...Chuck Klosterman: Thanks. Ummm. Titanic was the Chinese Democracy of film...but it worked. [laughs] Avatar is...it seemed like James Cameron was working on Titanic longer to me. Waterworld! Waterworld was Chinese Democracy. You know, Avatar, it just doesn't look that good, but maybe it'll be great. But I liked Chinese Democracy much more than Waterworld, obviously. I mean, Chinese Democracy, if nothing else, will always be remembered because it's become short hand for any project that goes on forever and costs too much money. Like, anytime someone is in their kitchen and trying to bake cookies, and they keep ruining the batches and throwing the cookies out and buying more ingredients, this is like the Chinese Democracy of cookie baking.I have a serious question. [geek stalker voice] Can you elaborate on why you take issue in the book with Edward Furlong's John Connor advising the T-100 to say "Hasta la vista baby" in T2: Judgement Day?Chuck Klosterman: Well...that is sort of a joke. [laughs] At the time the movie came out, the phrase, "Hasta la vista," was most associated with the artist Töne Löc. Before Terminator 2 came out, there was a Guns N' Roses video that was associated with Terminator 2 that was being shown constantly. So, when the kid said that—I dunno—that observation might have just been the remnant of a joke we were making at the time. [laughs] The thing is when I'm writing about time travel and all of these time travel films [in the book], I'm trying to write smart things but in the context of entertainment.Right. I understand that. But in the book you adamantly feel that it would be unlikely that Edward Furlong's John Connor would know of—or at least be a fan of–a rapper like Töne Löc. My feeling on this subject is that Furlong's character is a loner, so he probably likes Guns 'N Roses and finds Töne Löc funny, possibly in an ironic sense.Chuck Klosterman: Probably. Probably. [laughs] Yeah. You're making a good point.

Have you considered that Avatar may be the new Chinese Democracy? Obviously, this question is inspired by your amazing fake review from 2006 of Chinese Democracy...Chuck Klosterman: Thanks. Ummm. Titanic was the Chinese Democracy of film...but it worked. [laughs] Avatar is...it seemed like James Cameron was working on Titanic longer to me. Waterworld! Waterworld was Chinese Democracy. You know, Avatar, it just doesn't look that good, but maybe it'll be great. But I liked Chinese Democracy much more than Waterworld, obviously. I mean, Chinese Democracy, if nothing else, will always be remembered because it's become short hand for any project that goes on forever and costs too much money. Like, anytime someone is in their kitchen and trying to bake cookies, and they keep ruining the batches and throwing the cookies out and buying more ingredients, this is like the Chinese Democracy of cookie baking.I have a serious question. [geek stalker voice] Can you elaborate on why you take issue in the book with Edward Furlong's John Connor advising the T-100 to say "Hasta la vista baby" in T2: Judgement Day?Chuck Klosterman: Well...that is sort of a joke. [laughs] At the time the movie came out, the phrase, "Hasta la vista," was most associated with the artist Töne Löc. Before Terminator 2 came out, there was a Guns N' Roses video that was associated with Terminator 2 that was being shown constantly. So, when the kid said that—I dunno—that observation might have just been the remnant of a joke we were making at the time. [laughs] The thing is when I'm writing about time travel and all of these time travel films [in the book], I'm trying to write smart things but in the context of entertainment.Right. I understand that. But in the book you adamantly feel that it would be unlikely that Edward Furlong's John Connor would know of—or at least be a fan of–a rapper like Töne Löc. My feeling on this subject is that Furlong's character is a loner, so he probably likes Guns 'N Roses and finds Töne Löc funny, possibly in an ironic sense.Chuck Klosterman: Probably. Probably. [laughs] Yeah. You're making a good point. In the book, you discuss movies that you cannot stop watching when they appear on television. The chief example for you is Goodfellas. What about Goodfellas lends this quality to it?Chuck Klosterman: Goodfellas is just a really, really well made movie where if you catch the middle of it you can immediately tell which point of the movie you're at. And you inevitably know of a particular scene that's coming up, so you say, "Oh, I'll just watch that scene." And by the time you get to that scene, you're already really watching it.Gotcha. I agree that it's addictive in this way. I can't cite another movie where I anticipate just seeing actors smile more than Goodfellas. Smiles in that movie are like drugs.Chuck Klosterman: Yeah. And in that movie, Scorsese does a lot of things that should not work. Like, I hate voice over in movies, but it's awesome in that one. And using "Layla," it usually comes across as cheesy, but...if employed in other films it would be bad, but there are all of these things. If you do something wrong but you do it perfectly it ends up being better than something that's just normally good.For Chuck Klosterman's thoughts on the film adaptations of his books Killing Yourself to Live and Fargo Rock City, click here.Hunter Stephenson can be reached at h.attila/gmail and on Twitter.

In the book, you discuss movies that you cannot stop watching when they appear on television. The chief example for you is Goodfellas. What about Goodfellas lends this quality to it?Chuck Klosterman: Goodfellas is just a really, really well made movie where if you catch the middle of it you can immediately tell which point of the movie you're at. And you inevitably know of a particular scene that's coming up, so you say, "Oh, I'll just watch that scene." And by the time you get to that scene, you're already really watching it.Gotcha. I agree that it's addictive in this way. I can't cite another movie where I anticipate just seeing actors smile more than Goodfellas. Smiles in that movie are like drugs.Chuck Klosterman: Yeah. And in that movie, Scorsese does a lot of things that should not work. Like, I hate voice over in movies, but it's awesome in that one. And using "Layla," it usually comes across as cheesy, but...if employed in other films it would be bad, but there are all of these things. If you do something wrong but you do it perfectly it ends up being better than something that's just normally good.For Chuck Klosterman's thoughts on the film adaptations of his books Killing Yourself to Live and Fargo Rock City, click here.Hunter Stephenson can be reached at h.attila/gmail and on Twitter.