The Dude Abides: Revisiting The Peculiar Charms Of 'The Big Lebowski' 20 Years Later

The writing-directing duo of Joel and Ethan Coen have surpassed themselves time and again with Academy Award-winning films like Fargo and No Country for Old Men (the latter of which we revisited in a 10th-anniversary feature last October). On Sunday night, their longtime collaborator, Roger Deakins, finally won a long overdue Oscar for his cinematography. However, the Coen brothers movie that has endured as their most quotable cult classic is actually one that received no Oscar recognition whatsoever.

On March 6, 1998, The Big Lebowski hit theaters nationwide, introducing us to a new stable of colorful Coen characters. Like their bowling partner, Donny, The Dude and Walter Sobchak — played by Jeff Bridges and John Goodman, respectively — would be out of their element at an awards ceremony, anyway. When Bridges won Best Actor for Crazy Heart in 2010, it was surreal enough to see him sporting the same bearded look while clutching a golden trophy, tossing out words like "groovy" on stage in the Kodak Theatre.

Lack of awards notwithstanding, The Big Lebowski has, over the last two decades, proven its staying power as a cultural phenomenon. It's a movie that spawned its own annual festival, Lebowski Fest, not to mention its own religion, Dudeism. As a matter of fact, today is a high holy day in the Dudeist calendar. It's the Day of the Dude. So break out the White Russians, and let's celebrate by taking a look back at The Big Lebowski on its 20th anniversary.

The Ultimate Hang-Out Movie

The Big Lebowski is the ultimate hang-out movie. It's a movie you can watch with friends or put on because the characters are like your friends and you want to spend time with them. From the moment the Dude comes shuffling on-screen in his bathrobe and sandals and proceeds to start sniff-testing cartons of half-and-half creamer in the milk aisle, there's a humorous, endearing quality to this guy. It helps that you've got the Stranger's cowboy voiceover, describing the Dude as a man for his time and place. It's as if the slacker soul of the '90s were distilled into the perfect form of this one supermarket slob. A hapless individual, continually put-upon by life, the Dude returns home, only to be assaulted and have his rug peed on by goons. "It really tied the room together," that rug.

The desecration of the Dude's rug sets in motion the film's nominal plot, two hours of sublime nonsense that His Dudeness blows through like the tumbleweed seen tumbling out to the shore of the Pacific — as far west as it can go — in the movie's opening credits. He's like some long-lost pal from one's youth who never changed but just went right on being his old goofball self. You can check back on him anytime and he'll always be there for you because the Dude abides, and so does Walter.

The Coen Brothers based both characters on real-life people, but they also wisely chose to set the film in a bowling environment, because, as they put it, "it's a very social sport where you can sit around and drink and smoke while engaging in inane conversation." When Walter is introduced, he's in the middle of a conversation with the Dude that immediately sets the tone for their bickering relationship and Walter's affectionate belligerence toward Donny. It feels like we already know these schlubs.

In the midst of such memorable sidebar conversations, it's easy to forget that The Big Lebowski is an L.A. movie, one of a handful of great turn-of-millennium films set in the City of Angels (the list also includes a number of other films we've covered since last year, like Boogie Nights, L.A. Confidential, and Mulholland Drive.) That setting, however, is actually integral to the film's genetic make-up as a Raymond-Chandler-inspired mystery with "a hopelessly complex plot that's ultimately unimportant," as the Coens called it.

The Politics of the Dude

On the surface, The Big Lebowski is a film that would seem to resist any kind of heady interpretation. It can be enriching to dig into the subtext of movies, but imagine trying to explain to El Duderino what his story means. His eyes would probably glaze right over until he mustered up a reply of, "Yeah, well, you know, that's just like, uh, your opinion, man."

Yet The Big Lebowski is littered with political and even religious references that do make it seem like there's more going on in this movie than meets the eye, maybe even more than the filmmakers were aware of at the time. Set during the Gulf War, there's an eerie little coincidence at the beginning of the movie where the Dude is writing out a personal check for 69 cents, and he looks up at a TV where President George H.W. Bush is talking about how the Iraqi aggression against Kuwait "will not stand." The date on the Dude's check? September 11.

On that same date in 2008, Slate ran an article about the movie's prescient politics, how the figure of Walter — the gun-toting Vietnam vet who evinces "strong support for the State of Israel," even though he himself is Polish Catholic, not Jewish — may have actually foreseen the growing neoconservative influence in America. The 2003 invasion of Iraq actually began five years and two weeks to the day after the film's theatrical release. "Entering a world of pain," indeed.

Professing pacifism, the Dude doesn't just rock a Jesus beard; he strikes a literal Jesus Christ pose, holding his arms out at one point like a man hanging on a cross. Later, he can be seen doing carpentry, hammering nails into a wooden board in an effort to brace his front door against intruders.

Taking Her Easy

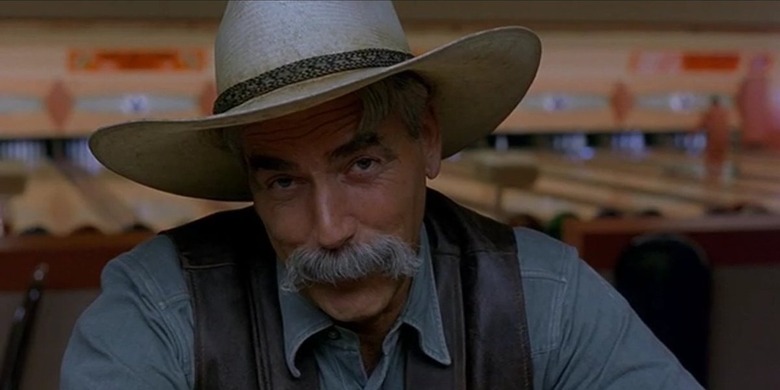

At the end of the movie, when Sam Elliot's all-knowing Stranger shows up again at the bar and breaks the fourth wall, looking straight into the camera and addressing the audience, he says, "It's good knowing he's out there, the Dude. Takin' her easy for all us sinners."

Maybe after hearing things like these, the Dude would admit, as he does in the movie: "You know, you're right. There is an unspoken message here." It seems likely that rather than trying to make any grand statement, the Coens were just using these things as character bits, the trappings of an idiosyncratic story they were trying to tell. With the camera fixating on the midsection of overweight bowlers, that story just so happened to be a good-natured riff on American culture back when it was still possible to have something like that, before the cynicism of the post-9/11 world set in.

Whatever else it is, The Big Lebowski is one of those infinitely rewatchable movies that reveals new delights every time you see it. You can luxuriate in the film's dialogue and just enjoy it on that level ("Also, Dude, Chinaman is not the preferred nomenclature"), or you can convert to Dudeism and make this movie a way of life.