How Did This Get Made: A Conversation With Metrov, Writer Of Solarbabies

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1970, an L.A.-born artist who went by the name "Metrov" moved to New York City. He began the decade working as a designer for the famed Push Pin Studios and then eventually made a name for himself as a fine arts painter, working out of a loft studio across the street from Andy Warhol's Factory. In 1979, inspired by a friend and guerilla filmmaker, Metrov came up with an idea for a low-budget, high-concept movie he wanted to direct: Solarbabies. This is a story about what happened next—how it was sold to Mel Brooks, how it was directed by a choreographer—and why, by the time Solarbabies was finally shot, its creator was no longer involved in his creation.

Solarbabies Oral History

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Solarbabies edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: In a sun-scorched post-apocalyptic world, a group of orphans spend their time playing games and defying the tyrannical "Protectorate." When one of the orphans discovers a strange sphere, it leads to an all-out struggle between good and evil.Tagline: Who Will Rule the Future?

Prologue

Metrov: I was called in and Mel explained to me that the script was a piece of shit. He was ready to drop the project. So, in the hopes of keeping Solarbabies alive, I suggested that he give me a chance to write the next draft. Mel looked at me and, in a very soft voice, he said, "Okay...go ahead and write it." And then, screaming at the top of his lungs, he said, "I GUARENTEE IT'LL END UP IN THE GODDAMN CONFETTI MACHINE IN FIVE MINUTES."

CUT TO: A few years earlier...

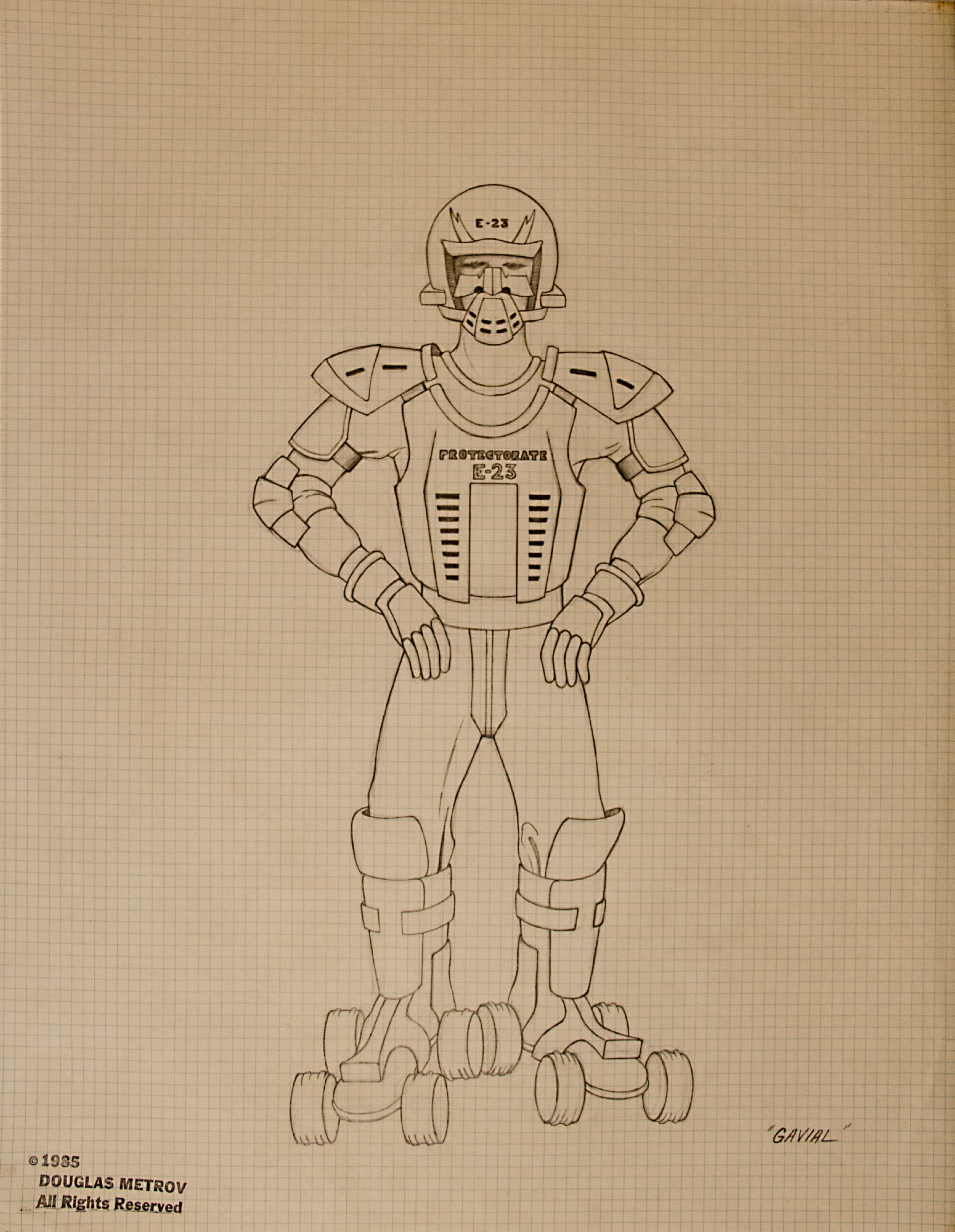

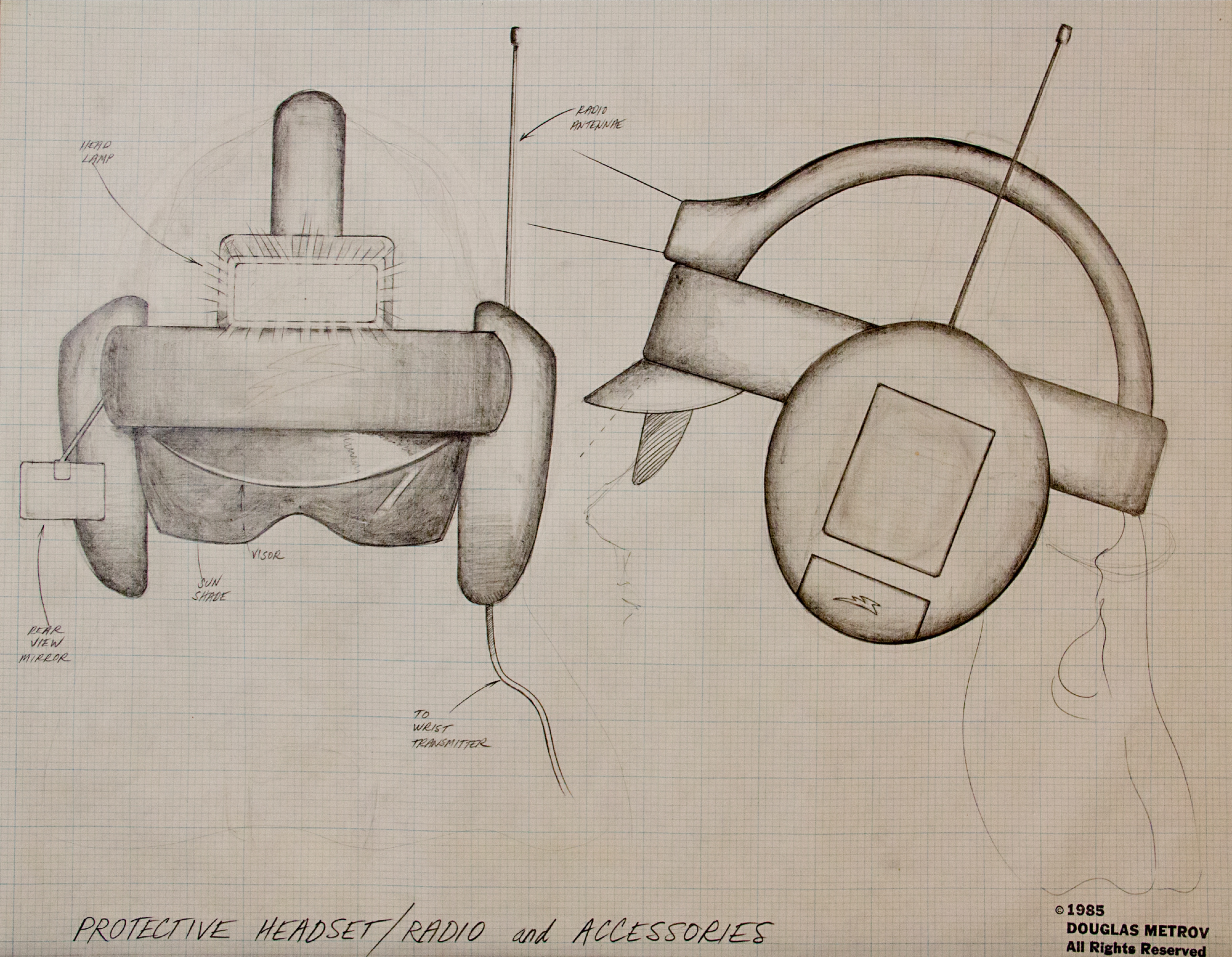

Part 1: A Little Rascals of the Future

Blake Harris: If I understand correctly, the whole idea for Solarbabies began with you. Though, at the time, you weren't even in the film business. You were a fine artist living in Manhattan. So how did this all start?Metrov: Well, I had actually gone to film school at UCLA, but I didn't go down that path was because I had no idea how to raise millions of dollars to make a movie. Then I became friends with Abel Ferrara. Do you know Abel? He's made a bunch of underground classics. One of them was this crazy movie called Driller Killer, which I watched him make for under $100,000. So I sort of learned the guerilla filmmaking process and that you didn't need millions of dollars to make a feature film. So that's when I came up with the idea for Solarbabies.Blake Harris: And tell me more about that original idea.Metrov: Sure. I was very influenced by George Lucas and Spielberg at the time. I especially liked Lucas' first film THX 1138, which had this sort of all-white motif. So Solarbabies, visually, the design was modeled after THX 1138; the kids wore all white, they were living in this white world set against the desert. It was almost like a Little Rascals of the future.Blake Harris: [laughter]Metrov: It was a story about these kids who were very quaint and charming and inventive. They'd sneak out of their orphanage at night and play this game on roller skates with sticks and a ball. And one night, the little kid finds this magical glowing sphere and they learn that they can incorporate it into their game. But then someone steals it from them, so they go on this adventure across the desert in order to retrieve their magical sphere; which, by this point, they're sort of able to communicate with. And roller-skating was really big at the time—people had started doing it outdoors—so I guess the roller-skating thing was in my head and I came up with this idea of the kids going on an adventure across the desert on roller skates.Blake Harris: You mentioned these kids were inventive. In what way?Metrov: Like on their adventure they have to cross a ravine. So how do they do it? They build a giant kite and fly themselves over the water one by one. Or another example: They'd send a mouse up on a balloon to scout ahead for them and indicate which way they should go. These kids, they were always coming up with contraptions. They were inventive. And the world they inhabited was inventive too. Like at one point they come to a place called Tire Town, where everything is made out of old tires—the clothing, the homes, everything. And, like I said, I was very adamant about this THX look. This all sort of white look. I'm not sure how else to describe it except that it was very original, very unique, very charming and sort of quaint.Blake Harris: So what was the next step for you? Did you write a script?Metrov: I wrote up a treatment, it was 32 pages long and included pencil drawings. Then around 1980, I left Manhattan and moved back to Los Angeles. So I started showing it around—this 32-page treatment—and people found it interesting. One of those people was Walon Green, a sort of legendary writer guy who was famous for writing The Wild Bunch. Walon liked the treatment and he said, "It's funny, I just got a call from this producer named Mark Johnson." A few years later, Mark went on to win the Academy Award for producing Rain Man, but at the time he hadn't produced anything yet. He was just a kid starting out—he'd recently worked as an assistant director to Mel Brooks—and even though he thought my treatment was interesting, he didn't really know what to do with it.Blake Harris: I imagine part of that had to do with the fact that you'd never written or directed a film before, right? So even if they liked this idea, they didn't really have much of an idea what it might look like up on the big screen.Metrov: Exactly. So eventually I had the idea to present the concept as a computerized slide presentation. In other words, it was a slide show that could run automatically and sync with this music. And this was 1980 or so, computers hadn't quite hit yet, so no one had ever seen a movie presentation like this before.Blake Harris: And what did you actually present?Metrov: So I got a bunch of kids together, dressed them up in costumes, put them on roller skates and took them out to the countryside. Photographed them skating through scenes in the movie. It was sort of a broad strokes sketch of the whole movie concept. And we photographed this on 35mm still film—which was the same resolution as the film stock at that time—so I was able to project this presentation onto a full-size theater screen. I wrote the music for it, another kid did the voiceover narration and we put on this 12-minute long slide show that was quite powerful.

Part 3: This Could Be Your Star Wars

Metrov: So one of the people who saw this slide show was Mark Johnson and he was kind of blown away by it. He brought me to several people in Hollywood, to give them the presentation, and one of them was Mel Brooks. Mel loved it and, after the screening, we went up to his office and made a deal. He was going to make my movie and I was going to direct. Like I said, it was quite a powerful presentation. He actually even gave me an office on the Zoetrope lot. Mel hired some hot young writer (whose name I can't remember) to turn my treatment into a screenplay and, while he was happening, I focused on developing other aspects of the film.Blake Harris: That's incredible. But I have a question. You sort of began this endeavor based on the idea that you could make a movie for around $100,000. At what point did the plan become for this to be a bigger, Hollywood-produced film?Metrov: When I brought it to Mel Brooks I told him I wanted $2 million to make this movie. I had started off wanting to make a movie for $100,000. Then I started meeting people who were actually in the business who, I guess, gave me the confidence to up the budget. So I told Mel I wanted to make this small movie for $2 million and he was supportive. He was very supportive. But what I didn't realize was that people in his camp—they were getting very excited about this project—and they were telling him, "Hey Mel, this could be your Star Wars. This really has a lot of potential!" But, these people would tell him, Metrov can't direct it because it has to have a bigger budget—at least $20 million to make a Star Wars-competitive movie—and Metrov is just a first-time director. He can't do that. But Mel kept fighting them and he kept saying, "No, no, no, I believe in Metrov and his vision and I want him to make his little movie."Blake Harris: You had mentioned earlier that Mel Brooks hired a "hot young writer," which isn't surprising since you'd never written a script before. But you are, of course, credited as the cowriter on Solarbabies, along with Walon Green. How did that happen?Metrov: Yeah, so the guy Mel hired spent a year writing the screenplay. Mel gave him $100,000 and, after Mel read it, I was called in and Mel explained to me that the script was a piece of shit. He was ready to drop the project. So, in the hopes of keeping Solarbabies alive, I suggested that he give me a chance to write the next draft. Mel looked at me and, in a very soft voice, he said, "Okay...go ahead and write it." And then, screaming at the top of his lungs, he said, "I GUARENTEE IT'LL END UP IN THE GODDAMN CONFETTI MACHINE IN FIVE MINUTES."Blake Harris: Ha!Metrov: But, you know, I had a vision for this script, so I started writing it. I should also mention that Mel wasn't paying me to write the script—meaning that I was writing it on spec—but I didn't mind because I really believed in this movie. And somehow Walon Green came back into the picture since I'd made this deal with Brooksfilms, which was the really hot production company at the time. They had launched David Lynch's career by making The Elephant Man and everyone was saying, "Metrov's going to be the next David Lynch, blah blah blah." So I started writing the script and then I hooked up with Walon Green and he agreed to sort of guide me through it. I'd write, like, 20 pages at a time, send them to Walon and get back some notes. And then I'd write another 20 pages. We did it like that until we had the script written. In exchange for doing that, I promised that I wouldn't sell the script unless it had both of our names on it.Blake Harris: Since you wrote this on spec, Mel Brooks didn't own the screenplay. Meaning you didn't necessarily even need to share it with him (and his confetti machine). But did you? Were you still hoping to make the movie with him? Metrov: Definitely. He had believed in this idea from the beginning and was always very good to me. So I sent the script over for him and his people to read it. He was back east at the time, I remember. He was at Fire Island, vacationing during the summer, and he actually called to tell me how much he loved the script. Which was sort of an odd thing to do because he didn't own it yet. And so by telling me he loved it, he was kind of giving away his leverage. But, like I said, that wasn't a concern of mine. So I was very happy.Blake Harris: Did you end up doing additional drafts after that?Metrov: Well, what happened was they paid me Writer's Guild minimum, and they paid for my membership into the Writer's Guild. But...then they had to pay Walon Green, who was one of the highest paid writers in Hollywood at the time. And they weren't too happy about that. Mel was not happy about that. So they had to pay Walon Green all this money for his share of the script—for being, supposedly, the cowriter of the script—so after they had to pay Walon Green all this money, I guess Mel figured, "Well, I'm going to get my money's worth out of Walon Green." So Mel started rewriting my script with Walon Green. Between the two of them, again they didn't understand my vision, and they turned it into this silly piece of junk. And so I was sort of squeezed more and more out of the project. Then, along the way, those people in Mel's ear finally got their way. They convinced him to make this a bigger budget film and get someone else to direct it. Why they chose Alan Johnson? I don't know...Blake Harris: Yeah, that seemed like an odd decision. Given how projects like these can evolve, I'm not terribly surprised you were replaced. But I am pretty surprised it was by somebody with so little experience. I mean, Alan Johnson was a choreographer. A world-renowned one, to be sure, but it's not like he had directed a film like this before.Metrov: Yeah. I don't know. I believe he had choreographed "Springtime for Hitler" in the movie The Producers, which Mel won the Academy Award for. So Mel owed Johnson a favor. This choreographer. So Mel gave him my movie [a quiver of laughter] and let him direct it. And they made something very different than my original vision. Mel actually called me and they screened it for him the first time. "Metrov," he said, "I've got a disaster on my hands." So yeah, that's how it evolved from this $100,000 movie to this $20 million bomb.Blake Harris: As you've mentioned during this conversation, there were some red flags along the way—in terms of you being replaced as director—so I was curious how you felt when it actually happened. Were you crushed or, because there had been some writing on the wall, did it not come as a shock?Metrov: No, no, no. I was mortally devastated. For years I was devastated and angry. It was not a fun time.Blake Harris: I'm sorry...Metrov: Yeah, the whole thing was sort of mystifying. But I have to be grateful that the movie was made because that was somewhat of a miracle in itself. I just came into town with no track record whatsoever and got my first movie made and we all know that's a miracle in itself. So I spent the next, I don't know, 25 years trying to sell another screenplay. [laughing] Which never happened. I've written a zillion screenplays—well, not a zillion—and then I was still doing it when the business sort of changed and the studios started buying novels instead of original screenplays. So like a lot of other screenwriters, I started writing novels. And now I've come full circle and I'm back into my fine art painting career.Blake Harris: And how does it feel to be back at that?Metrov: Great. I'm having more fun than I've ever had.Blake Harris: Excellent! I always love a story with a happy ending. But one last question, or maybe it's not even a question: I just wanted to say that, after your experience on Solarbabies, I'm surprised (and impressed) that you kept writing.Metrov: Well, you know what? I guess it had something to do with my personality. In my mind, if I could get one movie made, I could get another movie made. So I was determined to sell another script. I wanted to sell a script for what would then become a hit movie, which would then allow me to direct the next film. Now, it didn't help that Solarbabies was a bomb. But the thing is, the more they said no to my scripts, the more I was determined to become a better writer and sell something. So I really dug in my heels and worked very hard. And now I'm a pretty good writer after 40 screenplays and eight novels. And even though I'm back to painting, I still write, of course. Right now, I'm working on an Instagram graphic novel sort of thing.Blake Harris: Awesome. That feels like a fitting way to end. With something original, unique, charming and sort of quaint.

Concept Art from the Original Solarbabies Treatment

The first installment of Metrov's "The Creature of Nu" Instagram series can be found here:https://www.instagram.com/p/BAaejCPRoxv/To see more of Metrov's work, you can visit his website: http://www.metrov.org/