How Did This Get Made: Lifeforce, The Original "Shlockbuster" (A Literary Documentary)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Space Vampires + Nudity – Coherent Plot = How Did This Get Made?!?!

Nobody sets out to make a bad movie. But the truth is, it happens all the time. And every time it does, there's a fun misadventure or cautionary tale that led to its creation. This is that story for the 1985 summer shlock buster Lifeforce.

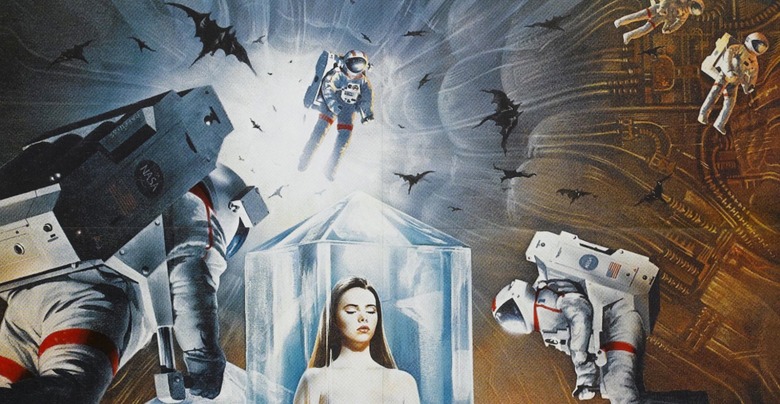

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies so bad they are amazing. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Lifeforce edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: After a space shuttle mission to investigate Halley's comet goes awry, a malicious race of space vampires arrive in London to suck the energy—or "lifeforce"—out of the city's unsuspecting population, unleashing a zombie plague.Tagline: The Cinematic Sci-Fi event of the Eighties

The story of how Lifeforce was made both begins and ends with a massacre. And, along the way, there occur horrors physical, psychological and philosophical. But it's not all bad, not even close. It's a carousel of wows and pows that help explain why Lifeforce did not turn out to be "the cinematic sci-fi event of the eighties."

Below is a narrative about what happened, as told through select archival material...

In the winter of 1972, an aspiring filmmaker named Tobe Hooper found himself inside of a crowded department store. It was the holiday season, the busy season, and after several minutes of Christmastime claustrophobia, Hooper became quite eager to remove himself from the situation. But leaving the store proved no easy feat—not with the flood of elbows and shoulders thwarting his exit—and so eventually, stifled and spun around, he wound up in the hardware department. And there, right below his very eyes, he noticed a rack filled with potential solutions: chainsaws.

If I grab one of those saws and start it up, Hooper thought, then that mob of people would have to part. With a revving chainsaw, they'd have to get out of my way! It was a fantastic thought, though obviously an unrealistic one. But nevertheless, the sordid notion stuck with him. Not only during his drive home later that day, but soon it blossomed into a chainsaw-wielding villain named Leatherface and, from there, a beautifully grotesque movie that would launch Tobe Hooper's career...

CUT TO: Two Years Later

Part 1: Who Will Survive and What Will be Left of Them?

Part 1: Who Will Survive and What Will be Left of Them?

On November 16, 1974, a couple hundred people showed up at the Empire Theatre in San Francisco to attend a highly anticipated sneak preview. As was customary at the time, the film to be shown at this "sneak" could not be formally announced in advance, but rumor strongly suggested that the theatre would be playing The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. That, however, is not the film that was screened...

SNEAK "CHAINSAW" IN ON "PELHAM" Angry Patrons Raise Issue of Unadvertised Infliction of Disgust

San Francisco Chronicle (November 19, 1974)

United Artists' "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three" has an R rating. So does Bryanston's "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre." But that doesn't mean they always appeal to the same audience......On hand from City Hall was Peter Bagatellos, an aide to supervisor Peter Tamaras. Threatening a lawsuit, Bagatellos asserted, "There's a good lawsuit here for intentional inflicting of mental disturbances. People were vomiting."

Throughout the final months of 1974, stories like these began popping up around the country. Horror movies had, of course, come and gone before, but there just seemed to be something uniquely disturbing, despicable and dazzling about Tobe Hooper's shoestring-budget slasher film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And shortly after its release, the national perception of this film quickly changed—elevating from a queasy curiosity to the must-see-movie of a decade—largely pushed to this point by influential film critic Rex Reed who called it the most terrifying film he had ever seen.

"[It] makes Psycho look like a nursery rhyme," Reed further elaborated, "and The Exorcist look like a comedy."

When it comes to the film business, there are all sorts of ways to measure success. Box office figures, ancillary rights deals, return on investment, etc. etc. But what, we might wonder, does any of this mean to the director and his career? Is it the box office numbers that provide peace of mind? Is it the reviews that drive his ego forward? Or is it the film—the piece of art itself—that can only ever truly satiate the creator's soul? Who can say? There's no true way to know. But one meaningful way to measure the coordinates of one's career is by answering this question: What's next?

With The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Tobe Hooper proved he could direct. He had talent, he had vision and he had that rare rugged ability to survive the making of an independent film. This was all evidenced in those 83 minutes on screen. And now, because of that, Hooper had plenty of options for what to do next.

Some of what he chose to make in the following years was well received (like the miniseries Salem's Lot) whereas other projects were not so much (such as Eaten Alive). But regardless of how one felt about his work throughout the rest of the seventies, it's safe to say that nothing came close to matching the magic of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Heading into the eighties, one couldn't help but ask the dreaded question: Was "horror guru" Tobe Hooper actually just a one-hit wonder?

But any doubts about Hooper's future were likely instantly erased in December of 1980. That's because that's MGM tapped Tobe Hooper to direct a high-budget horror film that would be produced by Stephen Spielberg. A project with great potential called Poltergeist.

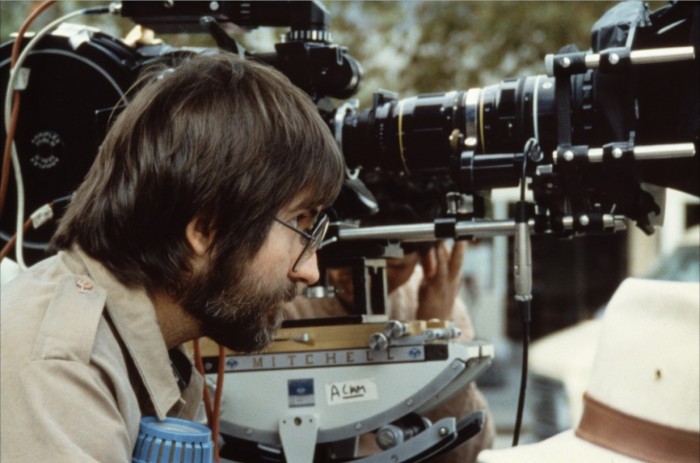

Part 2: Who Really Directed Poltergeist?Steven Spielberg has many talents, but here's one thing he isn't very good at: not directing. Or at least, in 1981, this appeared to be one of his worse qualities.

Part 2: Who Really Directed Poltergeist?Steven Spielberg has many talents, but here's one thing he isn't very good at: not directing. Or at least, in 1981, this appeared to be one of his worse qualities.

Although Spielberg had co-written and storyboarded Poltergeist, he was unable to direct the film because of a commitment he'd made to helm E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. So, as a huge fan of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, he and MGM selected Tobe Hooper to bring Poltergeist to life. And heading into the summer of 1982—with the film set to be released in June—the selection of Hooper appeared to be a terrific decision. The film finished on time, on budget and, most importantly, it turned out absolutely great. Tobe Hooper, it seemed, was poised for a new tier of greatness. But that, unfortunately, is where the problems begin.

In May 1982, weeks before Poltergeist opened, Steven Spielberg was interviewed by The Los Angeles Times and made the following comments:

Tobe isn't what you'd call a take-charge sort of guy. He's just not a strong presence on a movie set. If a question was asked and an answer wasn't immediately forthcoming, I'd jump up and say what we could do. Tobe would nod agreement, and that became the process of the collaboration... My enthusiasm for wanting to make 'Poltergeist' would have been difficult for any director I would have hired. It derived from my imagination and my experiences, and it came out of my typewriter. I felt a proprietary interest in this project that was stronger than if I was just an executive producer. I thought I'd be able to turn 'Poltergeist' over to a director and walk away. I was wrong."

Spielberg's insinuation was soon echoed by many involved in the film:

Mike Fenton (Casting Director): Did he [Tobe] direct the film? Not that I saw.Frank Marshall (Producer): "It all depends on your definition of director. The job of the producer is to get the film finished, and that's what we did. The creative force on this movie was Steven. Tobe was the director and was on the set every day. But Steven did the design for every story board and he was on the set every day except for three days when he was in Hawaii with [George] Lucas."Jobeth Williams (Actress): "It was a collaboration with Steven having the final say. Tobe had his own input, but I think we knew that Steven had the final say. Steven is a strong-minded person and knew what he wanted. We were lucky because we got input from two very imaginative people."

In an attempt to put this issue to rest, Stephen Spielberg wrote an open letter to Tobe Hooper that was published by The Hollywood Reporter on June 8, 1982 (four days after Poltergeist had opened):

To Tobe Hooper, Regrettably, some of the press has misunderstood the rather unique, creative relationship, which you and I shared throughout the making of "Poltergeist." I enjoyed your openness in allowing me, as a producer and a writer, a wide berth for creative involvement, just as I know you were happy with the freedom you had to direct "Poltergeist" so wonderfully. Through the screenplay you accepted a vision of this very intense movie from the start, and as the director, you delivered the goods. You performed professionally and responsibly throughout, and I want to wish you great success on your next project. Let's hope that "Poltergeist" brings as much pleasure to the general public as we experienced in our mutual effort. Sincerely, Steven Spielberg

Although Poltergeist didn't open particularly strong, the movie had legs and a long theatrical lifespan. And with each week of impressive box officer numbers—combined with the runaway success of E.T., which opened June 11—this "controversy" only seemed to grow louder.

WHO REALLY DIRECTED POLTERGEIST

Reading Eagle (June 27, 1982)

The controversy just won't go away. The Directors Guild now is probing whether producer Steven Spielberg is guilty of union violations for meddling in director Tobe Hooper's province. (The guild is no pushover; producer George Lucas was fined six figures for skipping director Irwin Kershner's name during the opening credits of "The Empire Strikes Back." Lucas withdrew from the union rather than pay). No word yet on who filed the complaint. Spielberg earlier had purchased trade ads thanking Hooper for the "wide berth" given him during filming, while Hooper has been mum but reportedly eager to start work on his next project and forget the brouhaha."

But what, exactly, would that next project be? Although Poltergeist had been a critical and commercial success, nobody in Hollywood seemed interested in working with the man who may or may not have directed it. Nobody, it turned out, except for Israeli cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus.

Part 3: The Unacceptability of $999,999

Part 3: The Unacceptability of $999,999

In August 1983, Tobe Hooper signed a three-picture deal with Cannon Films. The company—run by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus—had become something of a rogue juggernaut in the film industry following a corporate makeover that began in 1980 with a new cinematic mantra of "dropping exploitation pictures, making bigger films and casting with stars."

To that end, working with Hooper made a lot of sense for Golan and Globus; and, conversely, their new trajectory was perfectly aligned with what the exiled director had in mind. As a result, over the next few years, Hooper agreed to director a trio of films for Cannon: Spider-Man (whose rights had recently been acquired by Marvel), a sequel to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (to be made with a much higher budget than the original) and, most immediately, a sci-fi horror flick called Space Vampires.

Space Vampires was a film that Cannon had been trying to make for a few years now, based on Colin Wilson's 1976 novel "The Space Vampires." Since as far back as March 1980—when Golan and Globus were readying to shoot Space Vampires in Hawaii for $10 million—this film consistently appeared on the brink of being made. But for whatever reason, Space Vampires never made it into production. After several stalled starts, it perhaps seemed fated for a life only in development hell until, unexpectedly, a fellow producer took interest in the project.

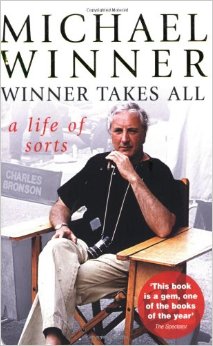

Below is an excerpt from "Winner Take All: A Life of Sorts" by Michael Winner:

Dino de Laurentiis, the Italian producer who'd made Death Wish, was in London in 1981 making a movie at Pinewood. He said, "Let's do another picture!" He had in mind a book he'd once optioned called Space Vampires. He asked me to call the agent to see if it was still available. The agent said a new option had been taken by two Israelis, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus...Menahem was very large. Yoram was rather small. They sat in my antiques-filled living room and I treated them like youngsters entering the industry. "We'd like to buy your opinion on Space Vampires," I said. Menahem looked up and replied in a guttural voice, "A million dollars!" The option was worth twenty thousand at most. I said, "Is that your final say on the matter?" Menahem said, "Yes. Come and make the picture for us. I said, "I'm negotiating on behalf of Dino de Laurentiis. You're telling me there's nothing you'd accept under a million dollars?" "No," said Menahem. "What about $999,999?" I asked. "No," said Menahem. I said to Dino, "They're a couple of nut cases!"

Nut cases or not, eventually both parties—Cannon and the Dino De Laurentiis company—decided to partner up and make this movie together. Their joint effort was to be directed by the Italian filmmaker Ferdinando Baldi (and this planned iteration of Space Vampires was to be released in 3-D).

Baldi eventually dropped out of the project. Michael Winner (author of the excerpt above) was then offered to direct, but ended up passing. So too, at some point, did Dino De Laurentiis who exited the project which, midway through 1983, left Goran and Globus without a captain for this spaceship.

Around this time, Tobe Hooper was struggling to find work at the studios. With limited options, he signed on to direct a $4 million sequel to Night of the Living Dead. Shortly after doing so, Menahem Golan offered him a chance to direct a much larger movie: Space Vampires, which was budgeted at $25 million. Tempted by the offer, Hooper exited Return of the Living Dead and was replaced with his hand picked successor: Dan O'Bannon, a well-known sci-fi filmmaker most famous for writing Alien.

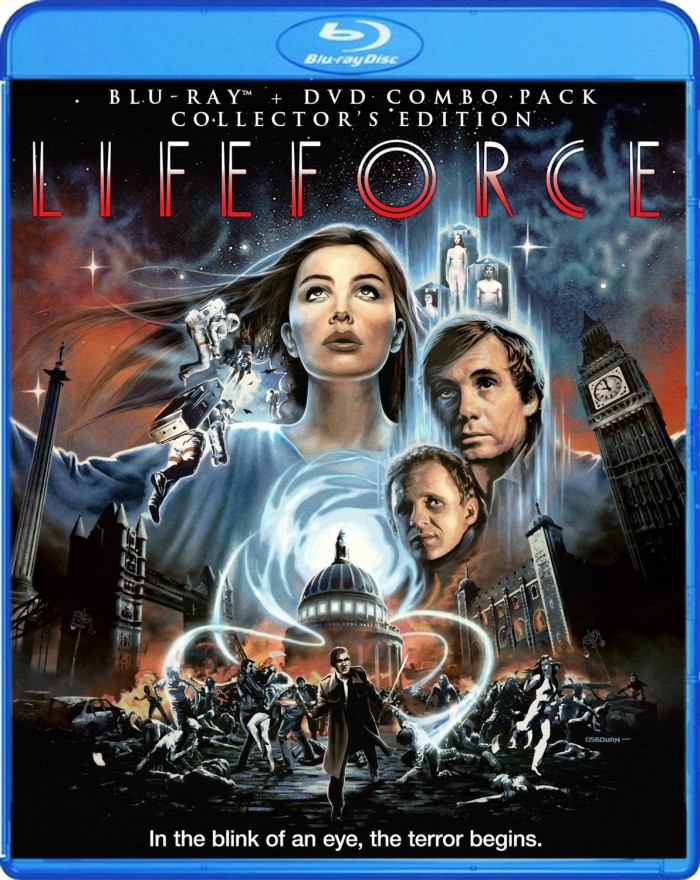

With Hooper now on board, Goram and Golum was finally able to move forward with production. And on February 6, 1984, at Elstree Studios in London, Cannon Films commenced principal photography on their most expensive production to date: Space Vampires, which would eventually be retitled Lifeforce.

Part 4: Cannon FodderIn October 2013, Arrow Films came out with a Blu-ray edition of Lifeforce. To accompany the release, Arrow hired filmmakers Calum Waddel and Naomi Holwill to create a feature-length documentary about the Making of Lifeforce. The documentary they crafted—directed by Waddel—came together so nicely that it won Home Cinema Choice's "Best Extra Feature of 2013." So, to learn more about the production Life Force, I spoke briefly with Calum Waddel. Blake: What do you think interested Tobe Hooper about directing Lifeforce?Calum: Tobe was reeling after the Poltergeist controversy but nevertheless had his name on a massive summer blockbuster. However, he had taken time out – I don't think it is any secret that he was having drug issues, indeed the producer of Lifeforce, Michael Kagan, says as much in our documentary and Zelda Rubenstein of Poltergeist had mentioned this publicly too. Golan and Globus would look at the grosses of films at the box office, though, and Tobe's Poltergeist had been a smashing success—regardless of whether or not Spielberg had the final say on what made it onto the screen. So Cannon signed Tobe to one of the biggest director deals in Hollywood at that time. In my own opinion, Tobe is a great eccentric genius and a vastly underrated master of making unique and quirky movies on a grand scale. Lifeforce certainly looks–stylistically at least—like the sort of film made by someone who had indeed helmed Poltergeist. It is just, of course, a car crash of a movie...Blake: Do you think that Golan and Globus had some idea of that going in? What do you think their expectations were at the time?Calum: I think they truly believed they had a huge summer hit on their handBlake: There is, of course, a very fragile and complex dynamic to every movie—millions of factors, actors, story elements, etc.—but in your opinion what was it about this movie that didn't work?Calum: Selling a summer film on a naked woman with big breasts destroying London was always going to be a hard sell. Plus the word of mouth was never going to be kind. Thematically, Lifeforce is simply not as sophisticated as the summer blockbusters that Spielberg was making/producing—it is all over the place and probably not suited to a mainstream multiplex audience.Blake: No, not at all.Calum: And after a riveting first 20 minutes the pace also slows down dramatically and the acting is variable too. It is not a 'bad' film, far from it, but its often dazzling aesthetics don't cover up the fact that its script and casting needed serious work. With that said, Tobe Hooper is such an individual talent that it is difficult not to love the sheer excess and daring of this super-expensive would-be blockbuster and to want to give the old guy a big hug for even dreaming up such a fantastic, never-to-be-repeated work of mad sci-fi horror madness!Blake: And lastly, bringing this back to you, I'm curious why you decided to make this movie? Why devote time, energy and creativity to something you described as "a car crash of a movie?"Calum: Because it is the crazy, excessive little pieces of movie history that appeal to me. I am no film snob at all – and I find formalist approaches to flop films or controversial movies far more enlightening than yet another discussion on accepted masterpieces such as Citizen Kane. So, basically, that was my approach to Cannon Fodder – to do an epic documentary on Lifeforce, a movie that helped to sink Cannon Films and whose reputation really needs more attention. From a purely academic standpoint too – it is a wet dream for anyone who likes a bit of Freud and Marx. I mean, a naked beautiful space woman comes to Earth and encourages same-sex life-swapping among men, gender-hopping as well as the entire destruction of patriarchy? And as a Scotsman, you have to love any movie that can destroy the corporate dump that is London.Like all good Making Of documentaries, Waddel's film includes a lot of heart, humor and histrionics. Below are a few of the most memorable (and insightful) nuggets revealed throughout the course of Cannon Fodder:John Grover (Editor): Very weird film. A lot of stuff that was completely unusable to start with...certain things that were never in the film—could never be in the film. Well certainly not in those days because of censorship problems. I mean, Mathilda May, when she came down the stairs the first time I absolutely gasped. I'd never seen such a pornographic shot. Not for a commercial film in those days. That sort of things was just never allowed.Sandra Exelby (Makeup Artist): We had this big discussion about Mathilda May. He [Hooper] said I want all her body hair off. And I said, "You can't do that. You can't do that Tobe." She's a young girl. At the time she was 18. 90% of the film she was stark naked walking about. You cannot take all the body hair away. He said, "Well I want the pubic hair as short as possible. And lighten it up. I don't really want to see it." So every morning I was on my knees [mimes cutting gesture] trimming and coloring and making it all look perfect."Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): Mathilda May, that plays the lead part over there, who is a French actress. Because we could not find an English actress that was willing to strip completely.Tobe Hooper (Director): It was hard to find casting for it here in London. Although probably, twenty or thirty actresses did screen tests for it...but I kept hearing about this ballerina in Paris. Mathilda. And I said, "Well, bring Mathilda over." And she was like the 50th or the 60th or the 70th and, you know, we finally found her."John Grover (Editor): Tremendous atmosphere working on the picture. I mean, half the crew was basically on coke and stuff like that because they were all into drugs! I think they'd been seduced by the lifeforce [chuckling]Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): I remember Tobe asked for more days for shooting certain scenes. And he came to me and I said to him, "Listen my friend: How many scenes do you think that you have to reshoot or shoot again?" And I don't remember the exact number, I think he said 20. I said, "Okay: you have five. Choose the five."Roger Stewart (Art Department): Production overran by some distance, what it was supposed to be...I was only supposed to be there for, I don't know, a couple of months. I ended up working there six or seven months. Which I was more than happy to do. But I guess if that is extrapolated through the other departments, you can see how something like that could overrun. How the bills just add up a horrendous scale. So yeah, there was a lot of money thrown at it, no doubt."Tobe Hooper (Director): I loved those guys because they didn't—Menahem and Yoram—because it wasn't just about making the money. They loved movies.John Grover (Editor): When we delivered Tobe's version to Golan and Globus, which was his director's cut and it had been dubbed. It was a little bit long, but it was a picture that worked. But the distributor—and I don't know if it was Tri-Star—they said the picture was too long and they wanted it shorter. And Tobe didn't want it shorter...then I went onto the other picture I was going onto [Labrynth] and Golan and Globus called somebody else in and they just slashed it. I say "slashed it" because they did.Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): Regretfully, the distribution company at the time was TriStar. And I think that they killed the film. They killed the film because, um, because they came back over here after they had a test screening, in New Jersey if I'm not mistaken, and the reactions were not good. I think that they approach the wrong way. The fact that they changed it from Space Vampires to Lifeforce was the biggest mistake. Because Space Vampires is a cult book. And has followers. It has followers. And when people come in expecting Lifeforce; it's not Lifeforce. It's Space Vampires.

Part 4: Cannon FodderIn October 2013, Arrow Films came out with a Blu-ray edition of Lifeforce. To accompany the release, Arrow hired filmmakers Calum Waddel and Naomi Holwill to create a feature-length documentary about the Making of Lifeforce. The documentary they crafted—directed by Waddel—came together so nicely that it won Home Cinema Choice's "Best Extra Feature of 2013." So, to learn more about the production Life Force, I spoke briefly with Calum Waddel. Blake: What do you think interested Tobe Hooper about directing Lifeforce?Calum: Tobe was reeling after the Poltergeist controversy but nevertheless had his name on a massive summer blockbuster. However, he had taken time out – I don't think it is any secret that he was having drug issues, indeed the producer of Lifeforce, Michael Kagan, says as much in our documentary and Zelda Rubenstein of Poltergeist had mentioned this publicly too. Golan and Globus would look at the grosses of films at the box office, though, and Tobe's Poltergeist had been a smashing success—regardless of whether or not Spielberg had the final say on what made it onto the screen. So Cannon signed Tobe to one of the biggest director deals in Hollywood at that time. In my own opinion, Tobe is a great eccentric genius and a vastly underrated master of making unique and quirky movies on a grand scale. Lifeforce certainly looks–stylistically at least—like the sort of film made by someone who had indeed helmed Poltergeist. It is just, of course, a car crash of a movie...Blake: Do you think that Golan and Globus had some idea of that going in? What do you think their expectations were at the time?Calum: I think they truly believed they had a huge summer hit on their handBlake: There is, of course, a very fragile and complex dynamic to every movie—millions of factors, actors, story elements, etc.—but in your opinion what was it about this movie that didn't work?Calum: Selling a summer film on a naked woman with big breasts destroying London was always going to be a hard sell. Plus the word of mouth was never going to be kind. Thematically, Lifeforce is simply not as sophisticated as the summer blockbusters that Spielberg was making/producing—it is all over the place and probably not suited to a mainstream multiplex audience.Blake: No, not at all.Calum: And after a riveting first 20 minutes the pace also slows down dramatically and the acting is variable too. It is not a 'bad' film, far from it, but its often dazzling aesthetics don't cover up the fact that its script and casting needed serious work. With that said, Tobe Hooper is such an individual talent that it is difficult not to love the sheer excess and daring of this super-expensive would-be blockbuster and to want to give the old guy a big hug for even dreaming up such a fantastic, never-to-be-repeated work of mad sci-fi horror madness!Blake: And lastly, bringing this back to you, I'm curious why you decided to make this movie? Why devote time, energy and creativity to something you described as "a car crash of a movie?"Calum: Because it is the crazy, excessive little pieces of movie history that appeal to me. I am no film snob at all – and I find formalist approaches to flop films or controversial movies far more enlightening than yet another discussion on accepted masterpieces such as Citizen Kane. So, basically, that was my approach to Cannon Fodder – to do an epic documentary on Lifeforce, a movie that helped to sink Cannon Films and whose reputation really needs more attention. From a purely academic standpoint too – it is a wet dream for anyone who likes a bit of Freud and Marx. I mean, a naked beautiful space woman comes to Earth and encourages same-sex life-swapping among men, gender-hopping as well as the entire destruction of patriarchy? And as a Scotsman, you have to love any movie that can destroy the corporate dump that is London.Like all good Making Of documentaries, Waddel's film includes a lot of heart, humor and histrionics. Below are a few of the most memorable (and insightful) nuggets revealed throughout the course of Cannon Fodder:John Grover (Editor): Very weird film. A lot of stuff that was completely unusable to start with...certain things that were never in the film—could never be in the film. Well certainly not in those days because of censorship problems. I mean, Mathilda May, when she came down the stairs the first time I absolutely gasped. I'd never seen such a pornographic shot. Not for a commercial film in those days. That sort of things was just never allowed.Sandra Exelby (Makeup Artist): We had this big discussion about Mathilda May. He [Hooper] said I want all her body hair off. And I said, "You can't do that. You can't do that Tobe." She's a young girl. At the time she was 18. 90% of the film she was stark naked walking about. You cannot take all the body hair away. He said, "Well I want the pubic hair as short as possible. And lighten it up. I don't really want to see it." So every morning I was on my knees [mimes cutting gesture] trimming and coloring and making it all look perfect."Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): Mathilda May, that plays the lead part over there, who is a French actress. Because we could not find an English actress that was willing to strip completely.Tobe Hooper (Director): It was hard to find casting for it here in London. Although probably, twenty or thirty actresses did screen tests for it...but I kept hearing about this ballerina in Paris. Mathilda. And I said, "Well, bring Mathilda over." And she was like the 50th or the 60th or the 70th and, you know, we finally found her."John Grover (Editor): Tremendous atmosphere working on the picture. I mean, half the crew was basically on coke and stuff like that because they were all into drugs! I think they'd been seduced by the lifeforce [chuckling]Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): I remember Tobe asked for more days for shooting certain scenes. And he came to me and I said to him, "Listen my friend: How many scenes do you think that you have to reshoot or shoot again?" And I don't remember the exact number, I think he said 20. I said, "Okay: you have five. Choose the five."Roger Stewart (Art Department): Production overran by some distance, what it was supposed to be...I was only supposed to be there for, I don't know, a couple of months. I ended up working there six or seven months. Which I was more than happy to do. But I guess if that is extrapolated through the other departments, you can see how something like that could overrun. How the bills just add up a horrendous scale. So yeah, there was a lot of money thrown at it, no doubt."Tobe Hooper (Director): I loved those guys because they didn't—Menahem and Yoram—because it wasn't just about making the money. They loved movies.John Grover (Editor): When we delivered Tobe's version to Golan and Globus, which was his director's cut and it had been dubbed. It was a little bit long, but it was a picture that worked. But the distributor—and I don't know if it was Tri-Star—they said the picture was too long and they wanted it shorter. And Tobe didn't want it shorter...then I went onto the other picture I was going onto [Labrynth] and Golan and Globus called somebody else in and they just slashed it. I say "slashed it" because they did.Michael Kagan (Associate Producer): Regretfully, the distribution company at the time was TriStar. And I think that they killed the film. They killed the film because, um, because they came back over here after they had a test screening, in New Jersey if I'm not mistaken, and the reactions were not good. I think that they approach the wrong way. The fact that they changed it from Space Vampires to Lifeforce was the biggest mistake. Because Space Vampires is a cult book. And has followers. It has followers. And when people come in expecting Lifeforce; it's not Lifeforce. It's Space Vampires. Part 5: Alternate Endings to a True Hollywood StoryLifeforce was released by TriStar on June 21, 1985. It proved to be neither a financial success nor was it a critical one. In fact—with write-ups like below—it was the worst reviewed movie of Tobe Hooper's career.NOT MUCH LIFE IN "LIFEFORCE" VILLAINS

Part 5: Alternate Endings to a True Hollywood StoryLifeforce was released by TriStar on June 21, 1985. It proved to be neither a financial success nor was it a critical one. In fact—with write-ups like below—it was the worst reviewed movie of Tobe Hooper's career.NOT MUCH LIFE IN "LIFEFORCE" VILLAINS

The New York Times (June 23, 1985)

By Janet Maslin

About 30 seconds into Tobe Hooper's "Lifeforce," two things become clear: that this film is going to make no sense, and that Hooper's directorial work on "Poltergeist" may indeed have been heavily influenced by Steven Spielberg, who wrote and co-produced that film. "Lifeforce" shows off Hooper's way with a whirling mass of protoplasm, just as "Poltergeist" did. But its style is shrill and fragmented enough to turn "Lifeforce" into hysterical vampire porn.

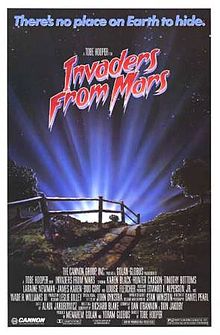

Despite the poor reviews, Hooper went on to fulfill his three-picture deal with Cannon. He next directed a remake of Invaders from Mars and then The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Both films were released in 1986, and both grossed less than $10 million at the box office. And following this string of unsuccessful releases, the options—both for Tobe Hooper and Cannon Films—were quite limited when it came to that very important question: What's next?

Despite the poor reviews, Hooper went on to fulfill his three-picture deal with Cannon. He next directed a remake of Invaders from Mars and then The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Both films were released in 1986, and both grossed less than $10 million at the box office. And following this string of unsuccessful releases, the options—both for Tobe Hooper and Cannon Films—were quite limited when it came to that very important question: What's next?

For Hooper, his ensuing work was mostly confined to television; either one-off episodes or made-for-TV movies. For Cannon, their appetite remained unprecedentedly large—in 1986, they produced a whopping 43 films—but by 1987 the company was reeling financially and was only a shell of itself by the end of the decade. And in 1994, after the release of Hellbound, Cannon formally shut its doors.

With stories like this it's so tempting to wonder what could have been? What if Cannon had just tempered their ambition? What if Spielberg had said things a bit differently to The Los Angeles Times? And what if, going back to 1972, Tobe Hooper hadn't felt such a visceral need to escape from a department store? Would different answers to any of the above have yielded a series of alternate endings?

What-ifs are infinitely fun to ponder but it's what-was that becomes endlessly real. And perhaps the best way to sum up what happened with Lifeforce—the context-free, net-net result of what once was Space Vampires—is with a final thought from the author who wrote the book on which all of this was based.

"John Fowles once told me that the film The Magus (made from his highly successful novel) was the worst movie ever made," wrote Colin Wilson in his autobiography Dreaming to Some Purpose. '[But] after seeing Lifeforce, I sent him a postcard, telling him I had done him one better."