Crimes Against Reality: On 'Zero Dark Thirty's' Depictions Of Torture

[The following article contains spoilers for Zero Dark Thirty]

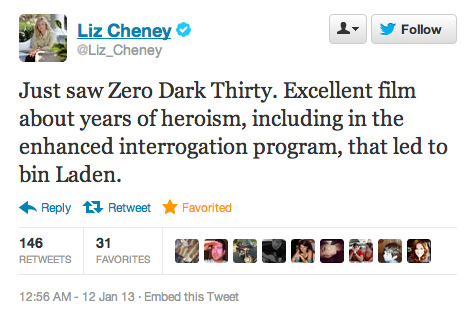

In the past month or so, it feels as though two opposing camps have been battling it out over Zero Dark Thirty: the film critics who laud it as one of the best films of the year, and commentators who believe that it in some way endorses torture or depicts it as effective. The latter group have also given time and effort to slamming the film (for example, by articulating that it "kind of sucked."). These opinions especially have inflamed film critics in a variety of ways; Scott Mendelson (a writer who I deeply respect and admire) recently wrote on the "moral outrage" that has resulted from Bigelow getting snubbed for a Best Director Oscar nomination due to the growing controversy over her film.

I think both parties have a point.

Here is a fact: the way popular culture depicts things matters. Movies "based on first-hand accounts of actual events" can shape our collective memory of history. They can inform U.S. or corporate policy. They can change the way we, as a country, do certain things.

Years ago, when I was marathoning early seasons of 24 with Devindra, I vividly remember the show's depictions of torture – Jack Bauer's gravely voice barking at a surely-guilty detainee in a ticking-time-bomb scenario. Nearly 100% of the time, Bauer got the information he was looking for. The overarching message that these scenes conveyed was that torture is effective. But so what? It's a TV show. People get that it's a TV show, that it's heavily fictionalized, and that it has no bearing on how things work in the real world, right?

In an article for the New Yorker in 2007, writer Jane Mayer describes the tension between professors at West Point, and their students, many of whom were 24 fans:

Gary Solis, a retired law professor who designed and taught the Law of War for Commanders curriculum at West Point...said that, under both U.S. and international law, "Jack Bauer is a criminal. In real life, he would be prosecuted." Yet the motto of many of his students was identical to Jack Bauer's: "Whatever it takes." His students were particularly impressed by a scene in which Bauer barges into a room where a stubborn suspect is being held, shoots him in one leg, and threatens to shoot the other if he doesn't talk. In less than ten seconds, the suspect reveals that his associates plan to assassinate the Secretary of Defense. Solis told me, "I tried to impress on them that this technique would open the wrong doors, but it was like trying to stomp out an anthill."

This isn't some suburban high school. Many of West Point's students rise to the upper echelons of the United States military. Does that mean that a television show impacted how we gather intelligence? I'm not ready to make that argument. But I think I think it is safe to say that depictions of torture and its efficacy help determine how we as a culture view it as a practice.

Does this mean that filmmakers have a responsibility to consider the impact of their work when they're crafting it, and factor that in to their decisionmaking process? Does this mean that filmmakers have to depict "all sides" of an argument, or present every possible interpretation of events? I've seen a lot of film critics respond to this question with the equivalent of "Heck no," and I agree with them. But the freedom to craft a piece of art/entertainment however you choose also means that if people see something they feel is inaccurate or damaging, they have every right to call you on it.

Which brings us to Zero Dark Thirty. For now, let's put aside the matter of whether or not the film is any good. For my part, I've discussed the film on several occasions and we on the /Filmcast all decided it was one of our favorite films of the year. The film's quality as an effective, moving piece of media is not at issue for us.

I think there are two distinct points in dispute — points that I have seen conflated with alarming frequency. After you've watched Zero Dark Thirty, you will likely leave with an opinion on the following two statements:

1) Torture was an effective information-gathering tool in the hunt for Osama Bin Laden.

2) Despite torture being effective, torture is so terrible and inhumane that we, as a country, should not participate in it.

I think it is possible to watch Zero Dark Thirty and believe that it does portray torture as effective, while also believing that its depictions of it render it an unfortunate and unforgivable choice. This is the distinction that is lost, time and again, in defenses for this film. For now, let's proceed under the assumption that the film is not in support of torture as a morally defensible practice (statement #2). There are many reasons to believe this, but the one that sticks out most clearly is Chastain's haunting expression as the film draws to a close — with tears streaming down her face, and eyes that seem to ask, "Was it all worth it?" Was it worth the countless enhanced interrogation sessions, the ruined and destroyed lives, the endless bloodshed? The answer is unclear but a lot of people might watch the film and believe that no, it wasn't worth it.

But for now, let's put that question aside, so that we may be as specific as possible. I personally don't believe the film "endorses" torture in the conventional sense of that term. But does the film depict it as effective, even as it depicts it as a deplorable practice?

It is a fact that many people will leave this film thinking that torture, in some way, helped lead to the killing of Osama Bin Laden. That's what political pundits are getting upset about — the fact that people think torture was effective at all. And if the pundits are correct in saying that the film sends people out of the theater with an understanding that torture was effective, then who is wrong? Filmgoers for not understanding what the film is trying to say? Or Bigelow for depicting torture irresponsibly? As usual, I think the answer lies somewhere in between.

To be sure, a lot of writers have watched this movie and have emerged with differing understanding of what exactly happened. It doesn't surprise me that no one can agree on the film's stance on torture: we can't even agree on what empirically happened during the course of the film! That being said, here are some scenes that I perceived to depict torture in an effective fashion (feel free to correct me in the comments if I have any of this incorrect):

1) Towards the beginning of the film, a brutal interrogation takes place with Ammar, while Maya (Chastain's character) is present. Despite the use of enhanced interrogation techniques such as waterboarding and sleep deprivation, Anmar doesn't break. Later on, Maya and Dan sit down with Anmar in a more comfortable environment and use deception to get the information they want out of him, rather than physical coercion.

2) At a crucial juncture in the film, a montage takes place during which Maya views videotapes of detainees, some of whom appear under duress, providing confirmation of Abu Ahmed's importance to Bin Laden's operation.

3) Later on in the film, Maya is seen interrogating a suspect while a larger male officer physically beats him at her command.

4) As the film reaches 2008 in its timeline, the election of Obama — as discussed in a conference room — is implied to metaphorically tie the hands of the CIA, who will no longer be allowed to use enhanced interrogation

A lot of hay has been made of the plot points in #1 above. According to screenwriter Mark Boal:

[T]he film shows that the guy was waterboarded, he doesn't say anything and there's an attack. It shows that the same detainee gives them some information, which was new to them, over a civilized lunch. And then it shows the [Jessica Chastain] character go back to the research room, and all this information is already there — from a number of detainees who are not being coerced. That is what's in the film, if you actually look at it as a movie and not a potential launching pad for a political statement.

Devin Faraci describes the Anmar sequence as follows:

That guy in the opening scene, the guy who wouldn't crack even when shoved in a tiny box, gives her the name after she tricks him. He withheld the information about the Saudi massacre, but since he's in custody, he doesn't know that the attack was successful. And because he's disoriented he's not sure whether or not he actually gave up the information. Maya tells him that he did, and that the attack was stopped, and resigned he begins giving up some information. Most of it wasn't of interest, but that one name became the lead that changed the hunt. We can split hairs here, saying that he only gave up the information after being waterboarded and tortured, but it was not torture that actually produced the name.

But in an even-handed piece for New York Book Review (well worth reading in its entirety), journalist Steve Coll refutes this widely propagated defense:

Some viewers might regard Ammar's final confession in the midst of warm hospitality as an example of torture that did not work, or worked only partially. In fact, this sequence of the film depicts precisely how the CIA's coercive interrogation regime was constructed to break prisoners, according to Jose Rodriguez Jr., a former leader of the CIA Clandestine Service...For if a CIA detainee initially refused to cooperate, interrogators applied "enhanced" techniques in an escalating sequence until the prisoner reached what Rodriguez calls "the compliant stage." Once the detainee "became complaint and agreed to cooperate," the harsh methods stopped, Rodriguez wrote, and the prisoner might be fed and coddled in reward for confessions he had not previously made.

As for the scenes described in point #2 above, Boal has already defended them (as quoted above). But Adam Serwer from Mother Jones had much the same take as I did:

[W]hat Boal refers to as "detainees who are not being coerced" is actually a montage of men being hung, hooded, and stripped of their clothing—not all of them are being coerced but it's clear that many of them are.

Let's buy the argument for the moment that the film does depict torture as effective. Maybe its depictions are accurate, and thus, they should not be criticized due to their accuracy! Even leaving aside the fact that acting CIA director Michael Morell has stated the film has exaggerated the role of coercive interrogation and that senators Feinstein, McCain, and Levin have stated they believe the film is "grossly inaccurate and misleading," the truth of the matter is that we ultimately can't know how effective torture really was for a few reasons. Specifically, much of what the CIA actually did was shrouded in secrecy.

What we do know is that the film leaves out a great deal about torture. In his piece about the film, Alex Gibney writes about the real-life interrogation of al-Qahtani, one of the characters that Anmar is based off of (emphasis mine):

Many writers have focused on the brutality of the al-Qahtani interrogation. They were right to do so. After all, even Susan Crawford, a Bush Administration official, ultimately admitted that his treatment was, in fact, "torture." Using techniques loosely based on the CIA's Kubark Interrogation Manual, and influenced by CIA's loony new playbook for questioning prisoners in the global war on terror, interrogators kept al-Qahtani from sleeping, force fed him liquids which caused him to urinate on himself and came close to killing him. But what many have overlooked is what happened to the interrogators during the al-Qahtani interrogation. They fell victim to what is called "force drift" (a tendency for interrogators to increase brutality when they don't get answers) and resorted to increasingly bizarre techniques. What are we to make of the fact that interrogators tried to get al-Qahtani to crack by using authorized "techniques" such as "invasion of space by female"; putting panties on his head, making him wear a "smiley-face" mask (I'm not making this up) and giving him dance lessons; making him watch puppet shows of him having sex with Osama bin Laden, administering forced enemas and making him crawl around like a dog. The point I'm making is that, when the full history of "Enhanced Interrogation Techniques" is told we will see that it was not only brutal and counterproductive but ridiculous.

Am I saying that Bigelow and Boal had an obligation to depict every single failed instance of torture? No. But if your film chooses to focus primarily on instances of torture in which it was effective, then — whether you intend to or not — your film is making a statement about how effective torture was in securing Bin Laden. And what your highly lauded and widely-seen film says about torture? It matters.

Steve Coll rightly points out, "In the recently concluded election campaign, Mitt Romney declared that he would revive the use of 'enhanced interrogation techniques.' Official torture is not an anathema in much of the United States; it is a credible policy choice. In public opinion polling, a bare majority of Americans opposes torturing prisoners in the struggle against terrorism, but public support for torture has risen significantly during the last several years, a change that the Stanford University intelligence scholar Amy Zegart has attributed in part to the influence of 'spy-themed entertainment.'" The implications of this are breathtaking to consider.

We all like to defend artists and their creativity here. I loved Zero Dark Thirty as a film and I think that Bigelow's resurgence in recent years is one of the best things to happen to filmmaking during my life is a cinephile. But I also think that the film renders torture as an instrumental part of Maya's quest. And if you think that doesn't matter beyond the world of film critics circles, you are kidding yourself.

David Chen lives and works in Seattle. You can follow him on Twitter or e-mail him at davechensemail(AT)gmail(DOT)com.