'Ad Astra' Spoiler Review: Brad Pitt's Zany Episodic Adventures In Cosmic Navel-Gazing

For much of his career, Brad Pitt has eschewed the path of the traditional leading man. A recent Buzzfeed article pegged Pitt as "a character actor trapped in a movie star's body." If you look back at his filmography, there's a clear pattern of Pitt playing off other actors as a kind of co-lead or ensemble head. This summer, he did it with Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. However, this pattern dates back at least twenty-five years, to when Pitt emerged as a full-fledged marquee name alongside Tom Cruise in Interview with the Vampire.

In Ad Astra, Pitt plays Roy McBride, an astronaut whose pulse rate never rises above 80 beats per minute. His journey to far-flung Neptune's orbit to hopefully find his father and potentially stop an Earth-threatening antimatter surge positions itself as Apocalypse Now in space. Helmed by James Gray, Ad Astra is something of an anomaly, both in Pitt's oeuvre and in the current blockbuster landscape. It's a mid-budget movie based on an original idea, not an existing media property, and it doesn't have a box office friendly director (like Pitt's last collaborator, Quentin Tarantino) attached to it.

Seeing a film of that nature open the same day in theaters around the world is refreshing, but it does place a burden of expectation on Ad Astra, as its occasionally heavy-handed script peddles thoughtfulness with thrills in an event movie marketplace. The film's title, which it never explains, is the Latin phrase for "to the stars." Audiences no longer look to movie stars as reliable brands in and of themselves. Here, Pitt is on his own in a way he's seldom been in his career. He can hold the screen, but can he elevate our heart rates?

To discuss that, we'll be rocketing straight into spoiler territory in 3, 2, 1...

Moon Pirates and Space Baboons

To its credit, Ad Astra keeps the set pieces rolling along for much of its running time, peppering its plot with as many discursive action beats as an existential sci-fi movie can hold. It hits its first such beat right out of the gate, as a cosmic electrical surge sends Roy into free fall from a towering space antenna. When debris from the antenna rips a hole in his parachute, there's a real sense of danger, even though it's a given that he's not going to die in the first reel and deprive us of moments we've seen in the trailers.

Roy soon learns from his superiors in SpaceCom — a branch of the U.S. military like the proposed, real-life Space Force — that the electrical surge originated from the Neptune base of the so-called "Lima Project." His father, Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), served as the leader of this project, disappearing with the first manned expedition to the outer solar system.

As the Neil Armstrong of Jupiter and Saturn (first man to both planets), Clifford enjoys a hero's reputation. He's obsessed with the search for intelligent life in the universe beyond Earth, which he views as "God's work." Though presumed dead, Roy eventually finds out that his father is alive and has gone Colonel Kurtz, outgrowing the small-minded moral constraints of us humans and thwarting a mutiny by cutting off the life support of his entire crew. "Purging the innocent with the guilty," he confesses.

Unlike "Alien Jones" (a.k.a. Tommy Lee), who prefers the simple pleasures of Boss coffee, Clifford the space frontiersman appears to be wired on crazy juice. The movie withholds his true nature at first, but it tips its hand pretty quickly when it starts having characters refer to Clifford as "the best of us." These same words were used to describe Dr. Mann, Matt Damon's character in Interstellar...and we all know how that turned out. Gray borrows from that movie and a lot of others here, even using the same cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema.

Before Ad Astra thickens its plot with the revelation of Clifford's crew-killing exploits, Roy must first fly commercially to the moon so he can catch his connecting flight to Mars and radio his deranged dad. In the near future — broadly defined as "a time of both hope and conflict" — inflation has apparently gotten so bad that it costs $125 for a blanket and pillow aboard a spaceplane.

Space tourism, it seems, isn't cheap. Years ago, Pitt was reportedly one of the celebrities who booked a deposit on a $200,000 Virgin Galactic space trip, so it makes sense, in a winking way, to have his character use that company for lunar access in Ad Astra.

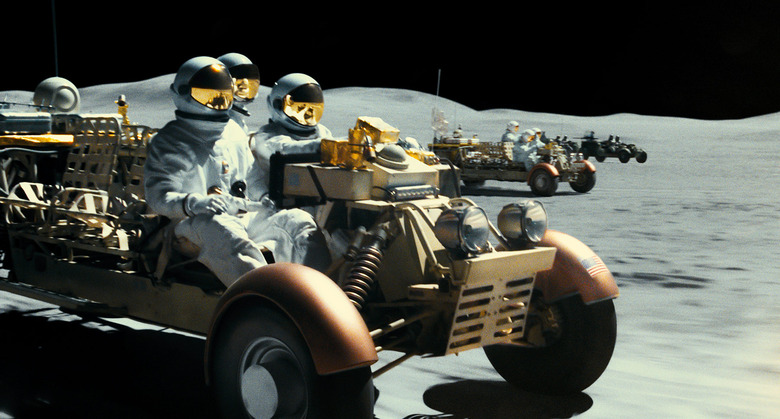

The moon boasts Yoshinoya signs. "We are world eaters," Roy narrates. And beef bowl eaters, the mind agrees. Jones isn't the only Space Cowboys alum on hand: there's also Donald Sutherland, who accompanies Roy on a lunar rover while moon pirates give chase. It's like a mini Mad Max: Fury Road scene, on moon buggies instead of dune buggies. The astronauts' reflective gold helmets even do look rather shiny and chrome.

Another episode in Roy's relentless space odyssey sees him docking on an animal research station, where he encounters feral, face-gnawing baboons. When the ill-fated captain who is giving Roy a ride insists on answering the station's mayday call, you can practically hear Martin Sheen screaming, "I told you not to stop," as he anticipates another disastrous outcome like the junk boat massacre in Apocalypse Now. Since this is Gray's loopy "Space-pocalypse Now," we're instead treated to killer primates swimming through zero gravity.

The Nuke Rocket to Neptune

After a string of collaborations with Joaquin Phoenix, Gray seems to have shifted into Heart of Darkness mode as of late. His last film, the underseen tale of jungle-exploring obsession, The Lost City of Z, was good but evanescent: the kind of movie that, if we're being honest and not all-knowing, passes out of mind and requires a Wikipedia refresher two years after viewing it. The same could be said of some of his other films. I know I saw and enjoyed We Own the Night, but The Yards fills me with a nagging uncertainty. I could swear I saw it, too, but memory-wise, the plot of both films is hazy.

Not so with Ad Astra. Whatever its faults, this trip upriver to the eighth and farthest planet in our solar system (R.I.P. Pluto) does manage to be eventful, at least on paper. It's a native Martian, played by Ruth Negga, who informs Roy that his father murdered her parents and the other members of the Lima Project. They concur that Roy should be part of the mission that will haul a nuke to Neptune and destroy the Lima Project base, thereby saving the universe from an uncontrolled release of antimatter.

Roy's daring stowaway attempt on a rocket during blast-off turns into a reluctant hijacking, and the ensuing scuffle results in the deaths of all three crew members. It leaves him alone on the rocket, bound for a blue planet...where men feel blue. "The son suffers the father's sins," Roy intones. He's becoming his father, and in case there was any doubt, we actually see Clifford's face superimposed over Roy's at one point. Toward the end, they're shown tethered together and tumbling in the void of space, until Roy finally learns to let go of his father and be his own man.

To paraphrase the title of an old Lost episode, "All the best [space] cowboys have daddy issues." (While we're on the subject of Space Cowboys again, the photos of Jones as a younger astronaut in this movie appear to be from that movie, leading the Internet to the only logical theory that Ad Astra and Space Cowboys inhabit the same cinematic universe.)

Prior to his solo excursion aboard the rocket, Roy has already begun unraveling, and the solitude primes him for a brief zero-gravity madness montage. We see and hear more snippets of Roy's father and wife, but these fragments of family aren't predicated on solid characters. They're less emotional and more hypothetical in nature — only liable to land if audience members project themselves onto Roy and imagine their own loved ones in place of those suggested onscreen.

By the end, Clifford has coalesced into a character, thanks to the actual appearance of Jones and his face-to-face interactions with Pitt onscreen. Roy's wife, however, remains a ghostly cipher, embodied by a peripheral Liv Tyler. She's there to imply the idea of human connection without actually being foregrounded as a flesh-and-blood participant in the story. (Oddly enough, Natasha Lyonne makes more of an impression in her "Welcome to Mars" cameo).

This is what left me lukewarm on Ad Astra as I walked out of the theater. The entire movie hinges on Pitt's performance and his character's internal life. It's an affecting performance and I admired the film's craftsmanship and intent. You can feel it fishing for profundity, but Gray renders much, if not all, of the subtext as text: spelling out the meaning of his movie in voiceovers and dialogue.

Heart On Its Spacesuit Sleeve

Roy recognizes his self-destructive side aloud right around the time that the news explains the surging phenomenon as a series of destructive electrical storms. He starts out the movie determined to "focus on the essential to the exclusion of all else" — even if it means keeping his pulse in check, showing no visible emotion, as his wife walks out on him. Rather than let the movie show us more moments like that, his voice simply tells us that he's walled himself off from relationships and has always has his eye on the exit when he's with people.

He talks about how a voyage of exploration can be used for escape, and all the while, his father's shadow lingers over him, this man who "could only see what was not there and missed what was right in front of him." If you're wired a certain way (like I am), lines like that might hit close to home, but how many members of the general moviegoing audience fit the Clifford/Roy M.O.? Maybe Ad Astra, like Roy, is too insular for its own good.

There's a part where Roy talks about the celestial objects his father helped map. He says something to the effect of, "Beneath their sublime surfaces, there was nothing." That line struck me as one that could apply to the movie's own surface-level delivery of its themes: themes which become less weighty and more obvious, perhaps, as they rise up from the deep end to the shallow end of the narrative.

That is not to say that the movie's message, as it were, is without value. It's just to say that Ad Astra is a film that wears its heart on its spacesuit sleeve, like the NASA logo. It's about what it's about, take it or leave it. Whether or not you find its message meaningful will depend on your own disposition as a human being and filmgoer.

When Roy records his last line, "I will live and love. Submit," it has the air of a "send tweet" declaration about it. Living and loving is good, and it's good that Roy recognizes the need for it now, but hearing his trip to Neptune reduced to that simple lesson leaves the whole journey feeling rather pat.

Would an astronaut who has braved this traumatic voyage and spent as much time isolating himself as Roy has really be equipped with the interpersonal skills to just jump back in and start living and loving again? It's one thing to have insight into yourself and why you are the way you are and what you need to do to change. It's another thing to apply that insight to your life in a practical manner.

Roy's determined to rely on those closest to him now, but outside the objectified wife who comes strolling back in at the last minute, who might that be? We never see Roy with any friends. At least in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Pitt's trailer-dwelling loner type had a pit bull to pal around with, along with his buddy Rick Dalton.

Thematically, I find Ad Astra resonant. Dramatically, it didn't nail me with any great catharsis in the theater on opening night. I suppose the sharpest stab, in terms of drama, came when Roy's estranged father (estranged in the sense that there's been a whole solar system between them) matter-of-factly stated that he never cared about Roy or his mother.

Beyond that, what Ad Astra left me with is more of a simmering impression. The more I thought about it, the more it haunted me on a personal level. In the end, I came away feeling that what I had watched was good, but not great, and certainly not a masterpiece, as some reviews (including our more positive non-spoiler one) have labelled it.

Introspection in the Year of Pitt

Looping back to where we started, Pitt has already been gaining Oscar buzz this year for his performances in Ad Astra and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. In a way, these two high-profile releases bring him full circle to the inception of his movie stardom a quarter of a century ago. After memorable supporting turns in early '90s films like Thelma & Louise and True Romance, 1994 brought us the first pseudo Year of Pitt with Interview with the Vampire and Legends of the Fall.

Since then, Pitt has co-starred with the likes of Morgan Freeman (Seven), Bruce Willis (12 Monkeys), Harrison Ford (The Devil's Own), Edward Norton (Fight Club), Jason Statham (Snatch), Robert Redford (Spy Game), George Clooney (Ocean's Eleven), Casey Affleck (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford), Michael Fassbender (Inglourious Basterds), and most recently, Leonardo DiCaprio (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood).

Many of those actors are leading men in their own right, whereas Pitt seems to thrive better as a wing man, juxtaposed against a more relatable everyman. He is perhaps the world's best co-star, masquerading as a movie star. Early 2010s films like the Oscar-nominated Moneyball, the crowd-displeaser Killing Them Softly, and the salvaged tentpole World War Z — all of which featured Pitt alone on their posters — register more as outliers in his career. Tree of Life and Fury both used younger actors as their entry point, while Pitt lingered in the background as a stern, larger-than-life father figure.

It's almost strange to see a film centered so throughly on a Brad Pitt character, as Ad Astra is. Despite his all-American good looks, there's an inscrutable quality to Pitt as a screen presence — as if he were somehow carved in granite and only to be understood from the outside in. When viewed through the eyes of a softer protagonist, that quality renders him a remote paragon of masculinity. (Admittedly, it lends itself well to the role of an astronaut on emotional lockdown.)

In that sense, maybe Ad Astra represents the perfect marriage of material with an actor. For most of us guys in the class of '99, Tyler Durden's cannonball shoulders and washboard abs remain unattainable. In the 2010s, his bruised and bloodied face has aged into the battle-hardened mien of a fine tank commander. Yet while Wardaddy might motivate, he doesn't always make for the most accessible movie hero.

Ad Astra circumvents this problem with quasi-Malickian voiceovers. Pitt carries the movie by his lonesome — and his character is lonesome. However, we're allowed inside Roy's head and he tells us what he's feeling in a series of psych evaluations. These evaluations see him sitting in front of a computer, responding to robotic commands, sometimes exploring his feelings outright, as one might in a therapy session.Ad Astra might not appeal to anyone outside a select cinema therapy group, but there is some merit to a story about a repressed individual who comes crashing down to Earth, reaching for outstretched hands, after an adventure in outer space. Roy's the escapist in all of us. He neglects his loved ones and anesthetizes himself until his buried humanity resurfaces in a need to connect. That need was always there but by movie's end, it becomes an overwhelming desire.

There's probably more than a little of the artist, or creative type, in Roy, as well. On that front, his supreme focus, his shelving of spouses, and mission-oriented brain exposes something faintly narcissistic about him... and perhaps the whole filmmaking enterprise of Ad Astra, too. It's as if Roy, the inward-looking ambassador of our species, ventures off on a rocket and beholds the wonder of the cosmos, only to shrug, glance back down at the pit of his own belly button (Pitt's pit), and declare himself alone in the knowable universe.

What we have here is essentially the introvert's guide to the galaxy. Right from the opening, Ad Astra almost chastises Roy and humankind for looking "to the stars." Why do any star-gazing when you could be navel-gazing?