The Holdovers Plagiarism Accusation Is Pretty Ridiculous

On the eve of the Oscars, Hollywood has been rocked by allegations that "The Holdovers" — one of the nominees for Best Screenplay — was "plagiarized line-by-line" from an unproduced script for a film called "Frisco," by "Luca" screenwriter Simon Stephenson. Plagiarism accusations and lawsuits are a dime a dozen in Hollywood, and rarely come to anything. But the language used by Stephenson in a 33-page document shared by Variety makes it sound like there's a real story here:

The meaningful entirety of the screenplay for THE HOLDOVERS has been copied from the FRISCO screenplay by transposition. This includes the FRISCO screenplay's entire story, structure, sequencing, scenes, sequential sub-beats within scenes, line-by-line substance of action and dialogue, characters, arcs, relationships, theme and tone. A majority of this has been done line-for-line, and a large number of unique and highly specific elements created in FRISCO are readily and unequivocally identifiable in THE HOLDOVER.

There's no indication that Stephenson has filed a lawsuit over the alleged plagiarism, though WGA West associate counsel Leila Azari advised him that this was "the most viable action" since the WGA itself doesn't arbitrate plagiarism accusations. Yet the story has already generated a great deal of buzz online, with many convinced that Stephenson has a watertight case against "The Holdovers" screenwriter David Hemingson and director Alexander Payne. The way the plagiarism is characterized above, it seems pretty open-and-shut.

Until you read the evidence, that is.

The Holdovers vs. Frisco

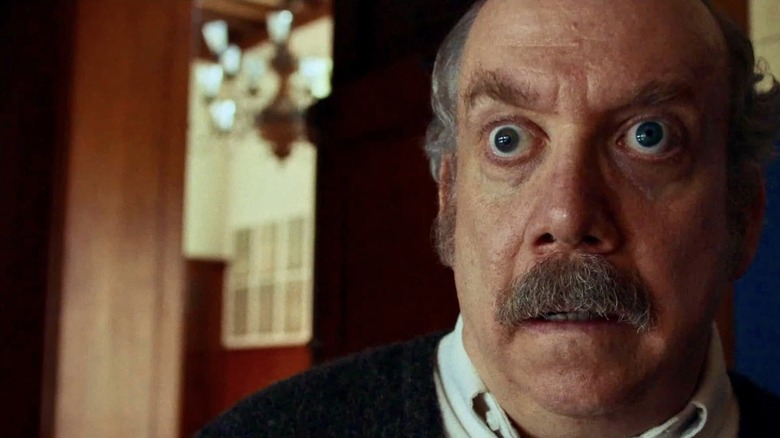

In case you haven't seen it, "The Holdovers" stars Paul Giamatti as a cranky, universally-hated history teacher who gets stuck at his New England boarding school over the holidays with a recently-bereaved cafeteria manager (Da'Vine Joy Randolph) and a smart but rebellious student (Dominic Sessa). Now, here's the logline for "Frisco," which was selected for the Black List in 2013:

A forty-something pediatric allergist, who specializes in the hazelnut and is facing a divorce, learns lessons in living from a wise-beyond-her-years terminally ill 15-year-old patient when she crashes his weekend trip to a conference in San Francisco.

There's a broadly similar premise: a grumpy older character and a precocious teenager are forced to spend time together. However, this is a pretty classic story set-up that can be found in countless titles — from "Gran Torino" to "The Last of Us." Payne has specifically acknowledged the 1935 French film "Merlusse" as being the main inspiration behind "The Holdovers." By itself, an older character and a younger character initially clashing but then becoming friends isn't really evidence of plagiarism. And based on the loglines alone, Stephenson's claim that the main characters in the two movies are "identical" and that the storylines are "identical to an extraordinary degree of specificity and abstraction" seems dubious. The evidence doesn't get any better from there.

'Symbolic billboard'/'Symbolic bottle of cognac'

Stephenson claims that the screenplay for "The Holdovers" was "transposed line-by-line" from his own screenplay — meaning that the details were changed in an effort to disguise the plagiarism, but the underlying similarities still shine through. For example, "The Holdovers" has a scene that takes place in an administrative office hallway, and "Frisco" has a scene that takes place in the vestibule between coaches on an Amtrak train. "Both are a hall."

That's ... quite a reach.

Later in the document, a library scene in "The Holdovers" is alleged to have been transposed from a "Frisco" scene set in the train's quiet carriage, because both locations are "a place known for silence." Elsewhere, the document claims that a "symbolic billboard" introduced on page 6 of the "Frisco" script has been transposed into a "symbolic bottle of cognac" introduced on page 6 of the "Holdovers" script. That's some very devious plagiarism indeed. Few would detect it, because billboards and bottles of cognac are radically different objects.

Other damning evidence of the "industrial scale" of transposition? Both movies begin with the main character complaining about something; both have a scene where a character is caught breaking the rules; and in both stories the main characters share a common interest. Sequences in the respective scripts are described as "identical" because both begin with an interior shot of a car and end with an exterior shot of the car. (INT. and EXT. are really the only two options for starting a slugline in a script. Unless perhaps the character is stuck halfway through a wall. But even then you'd probably just use INT./EXT.)

There's nothing new under the sun, or the Hollywood sign

Of course, movies that appear very different can actually share the same plot structure. However, this is less evidence of plagiarism and more evidence of patterns in storytelling that are as old as storytelling itself. There are certain narrative rhythms and character dynamics that have been proven to satisfyingly scratch an itch in the human brain, and Hollywood has whittled them down to a set of finely-tuned formulas. There's the classic hero's journey ("Star Wars," "Back to the Future," "Harry Potter," and a few million others). There's the Syd Field Paradigm. There's Michael Hauge's six-stage plot structure. And if you're feeling funky, there's Freytag's Pyramid.

Beneath these overarching structures lie countless familiar storytelling tropes. One of the "Frisco" script pages in the document is a scene that begins with one character entering and another character asking them, "What are you doing here?" — a screenwriting cliché so common that it was a running gag on "BoJack Horseman."

Thanks to this shared language of storytelling you could pick pretty much any two screenplays at random, grab a highlighter, and find a wealth of similarities on the same level as a symbolic billboard and a symbolic bottle of cognac. Try it with "The Sound of Music" and "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective," both of which begin with characters feeling discomfited by the main character's chaotic behavior. How do you solve a problem like Ventura?