'Star Trek' At 10: J.J. Abrams' 2009 Film Reboot Reinvigorated The Franchise With A Perfect Cast

Released ten years ago today, on May 8, 2009, director J.J. Abrams' Star Trek reboot is the cinematic equivalent of a rock band going mainstream. It's a hit remix version of an old song. Critically and commercially, the film was an unqualified success. Holding steady at 94%, edging out classic big-screen entries like The Wrath of Khan and First Contact, it remains the highest rated Star Trek movie on Rotten Tomatoes, as well as the top-grossing film in the series according to Box Office Mojo. Anytime a band goes mainstream, however, there's always going to be a contingent of old-school fans that you hear affecting a Leonard McCoy grumble. They were with the band from the beginning but now it's out there in the world and it belongs to everyone.

By the late 2000s, the Trek franchise was in a place where the overlapping runs of four straight television shows had ended—their viewership numbers falling victim to the law of diminishing returns. Fans like me, who grew up watching The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine in syndication, had lost touch with the final frontier. This is the movie that resuscitated that brand and opened the door to more adventures like the ones we're seeing now on Star Trek: Discovery and the ones we'll soon be seeing on the Captain Picard series.

As a storyteller, Abrams' great strength is character. His weakness is plot. Both of those qualities are on full display in Star Trek, but the movie has such a velocity to it (not unlike the U.S.S. Enterprise itself when traveling at warp speed) that the viewer can't help but get swept up in the youthful exuberance of this faster-than-light reboot. Beam yourselves aboard, then, and let's take a long and winding trek into Star Trek on its tenth anniversary.

TWIN PLANETS IN A UNITED FEDERATION

Now more than ever, the world needs Star Trek. At a time when it feels like Aldous Huxley and George Orwell's vision of the future is coming to pass — with civilization moving closer to the distracted dystopia of Brave New World and the post-truth landscape of 1984 — the world needs a reminder of the hopeful ideals that humanity can embody when it's not bent on dividing and destroying itself. There are different ways to inspire that kind of hope but the way the 2009 Trek film goes about it is by making us believe that people who are destined for greater things can overcome their differences and find a common purpose.

The movie seeks to distill the essence of all these classic '60s characters from Star Trek: The Original Series into new affable forms. It succeeds beautifully on that front. As James T. Kirk, the future captain of the Starship Enterprise, Chris Pine embodies a different kind of swagger than the one William Shatner originally brought to the role.

Shatner's Kirk had a quieter confidence to him. Pine's version of the character, as seen in this movie, is brash and has yet to learn the lessons that will make him a good leader—one who's capable of putting the good of his crew above his own life, even.

That scene after the bar fight in Iowa, where Kirk is talking to Captain Pike (played with great gravitas by Bruce Greenwood), is so well done that it becomes almost transcendent when Pike says, "Your father was captain of a starship for twelve minutes. He saved eight hundred lives, including your mother's. I dare you to do better." Sitting there watching that scene, you feel like you're the one being dared not to "settle for a less and ordinary life." You feel like you're the one "meant for something better, something special."

The movie draws immediate parallels between Kirk and Spock, showing how their trajectories on Earth and Vulcan align as much as they differ. Until he meets Dr. McCoy and makes his first Starfleet friend, no one sees anything in Kirk except for Pike. In the bar, he has burly cadets ganging up on him, dismissing him as a "townie." This is directly preceded by a couple of scenes where we see how Spock's half-human nature has made him the target of both overt and subtle discrimination.

It doesn't get much funnier than the first scene on Vulcan where we witness the hyperintelligent version of school kids taunting each other. "I presume you have prepared new insults for me today," says the young Spock, all stoic and resigned to his fate as the-kid-who-gets-picked-on. "Affirmative," replies one of the older bullies. Spock drolly intones, "This is your thirty-fifth attempt to elicit an emotional response from me." And then the restrained Vulcan equivalent of bullying begins.

Inheriting the black bangs and pointy ears of Leonard Nimoy's character, Zachary Quinto balances out the contradictions in an adult Spock who's still a paragon of rationality but also full of repressed rage. It's a show-stopping moment when he finally employs the famous Vulcan nerve pinch. The movie amps up the tension between him and Kirk, and there are some really good scenes where the two of them are hashing out their fundamental differences in approach as Starfleet members on the Enterprise bridge.

One of these is a tense mid-warp scene where Kirk pleads his case that the ship is flying into a trap. At that moment, we see how Kirk and Spock, the Earthling and the Vulcan — one impetuous, the other logical — are diametrically opposed in terms of their outward behavior. They couldn't be more different, yet we know from what we've seen of their lives leading up to Starfleet that they also have similar experiences running deep into their backgrounds.

Ultimately, they're able to get more done by putting aside pettiness and working together in the spirit of a United Federation. With the real world seemingly teetering on the brink of destruction in 2019, maybe we should all aspire to that model before some crazed Romulan (whose name references Nero Caesar) sets off a black hole causing the planet to implode.

REVIVING HUMANISM WITH FRESH FACES

If the essence of Star Trek can be regarded as humanism, then everything else — all the sociopolitical allegories the franchise has become known for over the years — would have to flow first from that foundation. Say what you will about it, but Abrams' film and the characters running through it are aggressively, irrepressibly human. This extends beyond Kirk and Spock to the rest of the quippy cast, most of whom were relative unknowns at the time.

2009 was the Year of Zoe Saldana. She was, by far, the best thing about Avatar, which you may remember as the fourth best science fiction movie of that year (with Star Trek, District 9, and Moon comprising the top three, of course). Here she delivers a star-making performance as Uhura, a character whose verbal tangos with Kirk are fun to watch and whose relationship with Spock feels more believable than it probably deserves to be, thanks largely to Saldana's emotive range. She can wield sarcasm but there's also a soulful quality to her that comes out in moments like the one when she and Spock are on the turbolift together and she's attempting to console him after the obliteration of his planet.

By revealing her as Spock's girlfriend, the movie does inadvertently set Uhura down the path toward underutilization. In Star Trek Into Darkness, she would fade to the background a bit, to the point where her concern and anger with Spock and his apparently casual willingness to sacrifice his life would become her whole subplot. In Star Trek, however, their relationship is merely one element of her character. She comes across as more well-rounded, enough so to justify the positioning of her face in DVD box art as the movie's third lead.

Karl Urban is a revelation. The beauty of this Trek is that it's the kind of movie that you can watch and rewatch, shifting fondness to a new favorite character every time you do. For me as a first-time viewer, the real MVP was Urban, whose scene-chewing turn as McCoy bowled me over in terms of how it channeled the spirit of the character without lapsing into imitation. As the curmudgeonly doctor, he's so pitch-perfect, talking out of the corner of his mouth, that you completely forget you're watching the same Viking-looking dude who led the Riders of Rohan in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

Speaking of Vikings, before there was Thor, God of Thunder, there was James T. Kirk's dad, George Kirk. People love to debate who the best movie Chris is, but whatever the answer, Star Trek introduced the world to two of them: not just Pine, but also Hemsworth (who would go on to star in his first Marvel movie two years later).

For viewers behind on their Edgar Wright films, Star Trek might have also been their first real exposure to Simon Pegg, who is so likable (and appropriately excitable) as chief engineer Montgomery "Scotty" Scott that there's almost a comedown that sets in when you see Pegg in his other, non-Trek roles. Likewise, Scotty's sidekick — for reference, his name is Keenser, and he's played by actor Deep Roy — deserves a shout-out as one of the movie's two best aliens, the other being the long-faced creature at the bar counter between Uhura and Kirk.

Foregoing the Monkees-inspired moptop of Walter Koenig, the late Anton Yelchin portrays a baby-faced Chekhov, one who's referred to as "Russian whiz kid" and whose accent is so thick that he has to keep repeating himself because even the voice-recognition computer can't understand what he's saying. John Cho's Hikaru Sulu, meanwhile, inhabits the other forward station on the Enterprise bridge. In this movie, Sulu is more straight-faced, less bug-eyed, than he was when he first employed his fencing sword in the Original Series episode "The Naked Time." His most meaningful contribution to the lives of some LGBTQ fans would come later.

All of these characters live in service to the utopian exemplar of Starfleet, which we're told functions as "a peacekeeping and humanitarian armada," but which can also be seen as a surrogate family unit for individual characters in individual crews like the one on board the Enterprise. To anyone who followed its previous adventures on television, the environment of the ship feels very much like home. Its living room is the bridge and its soundscape is iconic, not just the music, but also the sound effects: all the chirping communicators, whistling intercoms, swooshing doors, and other noises that make up the fabric of what we hear.

With his memorable music theme from the opening and closing credits on TV, Alexander Courage left some big shoes to fill, but composer Michael Giacchino wears them well. His score is its own character in the film. There's a sweep and — at key moments — a poignancy to it that gives the movie lift and bears it aloft, in new ways, to the soaring heights we've come to expect from Star Trek.

One moment that really tugs on the heartstrings, music-wise, is the birth of Kirk and death of his father. My favorite moment comes right after that, when the soundtrack transitions into the first cue of "Enterprising Young Men" and we see the escape pods: these little black dots breaking away against the backdrop of a huge, fiery sun, showing the terror and awe of humans in the cosmos. Then the title logo appears, lighting up like it's been waiting on the dark side of an adjacent planet.

That's a sequence that manages to convey the full, breathtaking wonder of Star Trek. Though not without its flaws (more on those in a second), this is a movie that's beautifully orchestrated both in the sense of its music and in the sense of its staging.

RED MATTER AND LIGHTNING STORMS IN SPACE

Updating Star Trek for the twenty-first century, making it flashier and more accessible to modern audiences, is a two-edged sword. On the one hand, it keeps Trek relevant and not too beholden to the past; on the other hand, you run the risk of compromising its integrity, betraying its core ethos. While motorcycle jumps set to Beastie Boys music and the pointless, pre-release, is-he-or-isn't-he Khan dance of Star Trek Into Darkness may have soured some fans on Abrams and the direction he took things, he deserves some credit for restoring Trek's vitality with an entertaining blockbuster. If the franchise was flatlining circa the late 2000s, then this is the film that broke out the defibrillator and set about re-electrifying it.

Having said that, Star Trek is one of those movies whose immediate glow seems to have worn off some in the intervening years. Among hardcore fans, at least, there's a mound of quibbles that is sure to arise like Tribbles in any room where Abrams and his overall effect on the franchise are being discussed. In 2013, at the annual Star Trek Convention in Las Vegas, Trekkies greeted Star Trek Into Darkness with boos and voted it the worst installment in the series, behind even Galaxy Quest, which is a spoof of Star Trek that's not actually part of the official franchise or even produced by the same movie studio.

This would be like Star Wars fans abandoning any pretense of impartiality and ranking The Last Jedi behind Spaceballs, just out of spite for Rian Johnson. In the present online climate, that's actually a believable scenario, but let's put that aside for now. Given that Trek Into Darkness (can we all agree that dropping the "Star" from the title would have made it less clunky?) is Abrams' direct sequel to Star Trek, it's possible there's some very real, residual distaste being felt for the 2009 film based on the 2013 film.

Indeed, people with a permanent Movie Sin Counter dinging inside their skulls will find much to nitpick in Star Trek. You don't have to be a hardcore Trekkie to dislike this film, of course, but I can understand why those people especially, the longtime fans, might have serious issues with Abrams' reboot. It's a less cerebral take on Star Trek, one that puts heart over head because it's more concerned with wrangling as much delight out of the mythos as possible.

Here's the thing: Star Trek is, first and foremost, a TV franchise. By its very design, it's best-suited to the format of the hour-long drama, which allows for both self-contained, episodic stories and serialized, long-form ones. Creator Gene Roddenberry originally pitched the series as "Wagon Train to the Stars," and trying to translate that to the big screen has always led to mixed results.

The long and short of it is that if you're going to watch the movies, you have to meet them on their own terms. Like Fight Club's "single-serving friend," the 2009 reboot is single-serving Star Trek, perfect for a plane ride, even if you never see it again (which you will, because it's the kind of flick that demands a revisit every few years). A fairer way to judge it, then, might be to stop comparing it to the TV shows and just sort it against the other twelve Trek movies, in which case it definitely belongs more in the "hit" than the "miss" column.

It's not as though the TV shows are free of embarrassment, anyway. Like any other long-running franchise, Star Trek has some goofy, graceless, outright cringe-worthy moments in its history. Shall we put on our nerd glasses and talk about Kirk vs. Gorn, and the Original Series punch that spawned the dubious tradition of "double ax-handles" in awkwardly choreographed fights?

The cynical response would be to ignore this history and insist that the reboot dumbed Trek down, raising the action quotient and sexing it up into a glib rendering for the masses: something that takes all the thought out of Trek and panders to the popcorn crowd. If we carry this line of thinking further, it's not a stretch to see the reboot as a complete mercenary endeavor, as opposed to something that was a labor of love for many people.

Admittedly, there are plot contrivances in the movie that might cause one's bullshit detector to bleep—much like James T. Kirk, giving a blank-faced pause before swearing in an ice cave at the unbelievable claims of Old Man Spock. This is, after all, a J.J. Abrams film. Personally, I like Abrams; I think he's that rare breed of director who has never made a bad movie. At the risk of trotting the Tomatometer out too much, it's worth noting that the five films he's directed are "Certified Fresh" across the boards. There, you see? Objectively not bad. Because the review aggregator says so. (I am aware that this is not true Vulcan logic and am being facetious).

Nevertheless, the bullshit detector, the poppycock radar, the Movie Sin Counter, whatever you want to call it, does go to red alert at odd intervals in Abrams' films, if and when they slow down enough (in-between requisite action beats) for you to catch your breath and think. In Star Wars: The Force Awakens, it was Rathtars and mind-numbing exposition about thermal oscillators that massaged the grief of thinking persons. In Star Trek, it's red matter and little snippets of dialogue for dummies, like the oft-repeated phrase, "a lightning storm in space."

With its "super ice cubes" for volcanoes, 300-year-old frozen men in torpedoes, and cheap resurrections via super blood serums, Star Trek Into Darkness is arguably sloppier. Credit where credit is due: screenwriting duo Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman penned the script for both films. Their best work has come when paired with Abrams, but Orci, who self-identifies as a Trekkie, may have engendered some ill when he lashed out at Into Darkness haters back in 2013. For his part, Kurtzman has continued to shepherd the franchise on TV, bringing it more into the melodrama realm with Star Trek: Discovery.

It's not a surprise that some would see it as a relief when Orci and Kurtzman's next script was abandoned and Simon Pegg stepped in to co-write Star Trek Beyond. Pegg, too, was clearly conscious of the dissatisfaction with Into Darkness, and by that point, he already had some experience running around in character as Scotty, trying to save an imperiled starship, saying, "I'm givin' her all she's got, Captain!"

"UNDER CONSTRUCTION" … IN HOLLYWOOD

The screenplay for Star Trek, it should be noted, isn't brain-dead. On the contrary, its humor is rather witty in places and the emotional beats are rousing, as well. Tell me you don't get a chuckle out of moments like Bones mouthing the phrase, "Green-blooded hobgoblin." You'd almost have to be a hobgoblin not to get a lump in your throat when Kirk's father is on his collision course with the Romulan ship, and he and Kirk's mother are naming their baby right as the acting captain is about to die.

"Whatever our lives might have been, if the time continuum was disrupted, our destinies have changed," Spock says. Moments like this and the above-mentioned one plug the film into universal themes of fate and familial love. That's the kind of story this movie is trying is tell. Star Trek's screenwriters were aiming at a wider audience; they needed to liberate their story from decades of franchise baggage, but they also needed to anchor it to the existing Trek mythology so as not to just flippantly disregard everything that came before it. By incorporating time travel and alternate realities into the narrative, they were able to spin Trek off into the quadrant where nothing is written, nothing is known, and the pleasure lies not only in the discovery of new things, but the rediscovery of old things.

Maybe it's not space that's the final frontier; maybe it's time. Either way, the makers of the 2009 Star Trek reboot admirably fulfilled the mission of seeking out new life in the universe, of boldly going where no Star Trek movie had gone before.

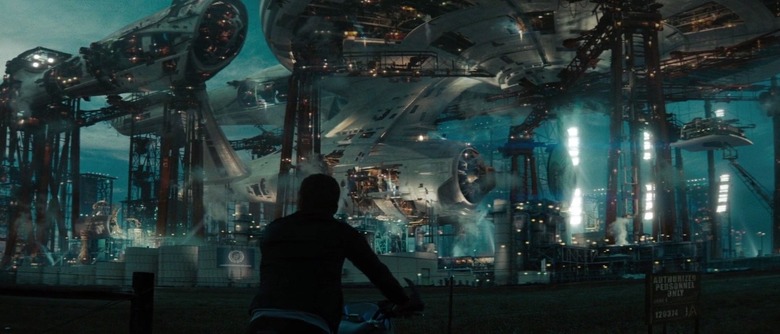

Abrams' overuse of lens flares may have become a joke, but the ones in this movie, coupled with the camera's perspective tilts, do give it the visual quality of a mind-bending journey. At the same time, the fact that Star Trek is not overindulgent in computer-generated imagery, the fact that Abrams and his crew used real locations and sets, adds a layer of realism to the film. When you're in Iowa with the young Kirk, and there are those huge hazy towers in the background, and the android-cop comes along on his hoverbike, it all feels like part of the real world.

On television, Star Trek, was, at its best, always thought-provoking in a way that allowed the viewer to tie it back to what was going on in the real world. The reboot's most thought-provoking moments come from its meta treatment of Trek. Maybe that makes it a hollow Hollywood construct, one whose inner workings lay exposed like those of the Enterprise itself in the film's enigmatic first teaser—which offered glimpses of welders building the ship up close, followed by the words, "Under Construction."

In the actual movie, Kirk sees the construction happening outside the shipyard on the ground in Iowa. The camera moves in behind him, letting us gaze at that ship, which holds the promise of so much destiny. Yet if Trek's destiny going forward is merely to cannibalize past highlights, and if our destiny as viewers is merely to get lost inside the looping dream of this fictional world, how is that ship any different from the deceptive Talosian illusions that caged Captain Pike in the pilot episode of The Original Series?

Star Trek: Discovery recently revisited Talosian territory, so it's worth remembering the pilot and its line: "When dreams become more important than reality, you give up travel, building, creating." Coming as it did in the very first episode of the series, that line could almost be read as a warning to the elaborate web of fandom that would spring up around Star Trek in the decades to come. Maybe we should all take a step back before we get too caught up in the fictional mythology of Trek and its alien worlds.

That said, if the reboot is, in some sense, a cage for the franchise and for the viewer, then it's as pleasant a prison as the IP zookeepers in Tinseltown ever constructed. Keep in mind, Pike was aware of his predicament, and some illusions can serve as a wake-up call, renewing one's appreciation for what one has back in the main reality (if not the real world, then at least the wide world of Trek on TV).

Flipping back through the 2009 film yearbook, cinephiles may recall that Star Trek was released the same summer as Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, a movie that landed squarely on the opposite end of the quality spectrum. Orci and Kurtzman also made up two-thirds of the writing team for that movie. Between it, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Terminator Salvation, and G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra, 2009 was a tough year for summer popcorn flicks.

The point is, anyone who thinks this Star Trek is bad maybe needs to go back and do a little comparative rewatching. Drawing as it does from cartoon toy mythology, Revenge of the Fallen is much less convincing on the plot level. Next to a nonsensical MacGuffin like the Matrix of Leadership, Star Trek's red matter at least sounds more plausible.

Unfortunately, the film brings back the late great Leonard Nimoy as Spock, only to saddle him with an info dump in the midst of a mind meld. It's sad to hear his frail voice become a puppet for plot exposition; and unless you believe in the gleeful serendipity of Lost Connections, it's criminally convenient that Kirk, the marooned mutineer, stumbles upon the elder Spock in a random cave on a random ice planet (#NotHoth). On that same planet, Scotty is also conveniently waiting for them in a Starfleet outpost, ready to be fed the deus ex machina equation that will allow him to invent trans-warp beaming right at the moment when Kirk most needs it to get back on the Enterprise.

These wonky plot mechanisms aside, it's all okay, really, because this Star Trek is superluminal. It distills the inherent optimism of the franchise down into the can of a quick energy drink that we can all slam back together at Quark's Bar on DS9. Shouldn't sci-fi nerds, by their nature, prefer quarks to qualms? What is a qualm, anyway? I've forgotten the definition of the word because it holds no meaning for me when I watch Star Trek ... a movie that doesn't have time for your concerns about plot holes ... not when it's busy conjuring that big black hole to eat the Vulcan planet.

With his home world destroyed, it starts to feel like Spock, the mythic "child of two worlds," is getting a new Superman-like origin whereby he'll become something akin to the last son of Vulcan instead of the last son of Krypton. That's alright: he's still got a single parent, as does Kirk. His human mother, played by Winona Ryder — then the biggest celebrity face in the movie (this side of Romulan Eric Bana and Starfleet Admiral Tyler Perry, that is) — dies simply because Bambi's mother died. It's tradition: one parent per hero. That's what happens in Disneyfied fairy tales.

It wouldn't be the last time Abrams directed one of those. If it pains you to see Kirk and Spock become the live-action Paramount Pictures equivalent of lion princes in a Disney animated feature, just know that there's probably some moviegoer out there who got drawn into the universe of Star Trek through the instant accessibility of this film. The movie is gateway Trek for neophytes, courtesy of Bad Robot Productions.

THE JOY OF J.J.

Coming at the tail end of the 2000s, Star Trek put Abrams at the forefront of a new generation of fans turned filmmakers who would, in the 2010s, set about remaking, remixing, and rebooting the well-known movies they grew up on. No longer would homages be confined to the underground gems and obscure foreign films that Quentin Tarantino had been stealthily repackaging for years.

Hollywood's (still-going) reboot-o-tron had already fired up with great success in the mid-2000s, courtesy of Batman Begins and Casino Royale. Star Trek is where the machine settled into a new groove. A few years down the road, in among all the other franchise wannabes with colons in their titles, even the good tentpoles would start to resemble each other, with The Avengers, Skyfall, and yes, Star Trek Into Darkness, all being faintly derivative of The Dark Knight—that movie where the villain plans to get caught all along just so he can stare out from a cell and then escape.

With Star Trek, you certainly could make the case — as others have — that Abrams, as director and field marshal, is the delinquent juvenile Kirk, cranking up the song "Sabotage" and driving the franchise over a cliff while trying to outrace some paternal shadow. Instead of his father, George Kirk, it's the legacy of his blockbuster forerunners, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, that has chased Abrams through most of his film career (including the Raiders of the Lost Ark-inspired foot chase in Star Trek Into Darkness). In his red Corvette, J.J.'s got Nokia product placement and a glove compartment full of mystery boxes. Han Solo's pair of gold dice hangs from the rearview mirror. There's also a bottle full of creative lightning that the boy furtively uncorks despite open container laws in California.

That's Abrams, or at least my perception of him. He's out there on the open road and his critics, all the Anton Egos of the world, are just bitter backseat drivers. The man has pretty much conquered Hollywood at this point. Love him or hate him, there's no denying that he's been instrumental in shaping American pop culture at the highest levels. Remember when M. Night Shyamalan was supposed to be the next Spielberg? With his nostalgia-driven forays into populist filmmaking (especially Super 8), Abrams consciously strives toward the same ideal.

He may have jumped starships to the galaxy far, far away, but first, Abrams had to make the jump from television to film. Like David Fincher, he started with a random franchise threequel. Mission: Impossible III put him on the movie director map, but Star Trek solidified him as one to watch, a filmmaker with a whole new pseudo-auteur cred.

The movie is an announcement: with it, Abrams let us know that he had truly arrived and would be an important force in the film industry. As reboots go, this one was monumental, the kind that shifted the earth beneath the feet of general moviegoers and made them realize that this thing called Star Trek was cool, not just something for Trekkies.

What really irks some fans, I think, is that Abrams gave Star Trek a space fantasy facelift. Then he had the temerity to abandon his dubious cosmetic procedure, flinging it aside at the first sign of Star Wars, as if, all along, the Enterprise was just keeping his butt warm for the Millennium Falcon.

Full disclosure: in addition to Star Trek, I'm a Star Wars fan from way, way back, which may go a long way toward explaining my irrational love for this iteration of Trek, if you're of the mind that this is Trek, by way of Wars. Nevertheless, as a child of these two worlds (much like Spock himself), what I'd like to know is ... why can't a toy model of the Starship Enterprise occupy the same shelf as a toy model of the Millennium Falcon? I'm genuinely asking because I have this feng shui problem in my entertainment room and the geomancy of J.J. is the only thing that seems to solve it.

Listen, we've established that J.J. is Kirk, so if Kirk's too busy munching on an apple to play by the rules of the Kobayashi Maru test, do you really think J.J.'s going to play by the rules of a no-win situation or even a win-lose situation? Oh, sure, the Western mind has been trained to see the world in those dichotomous terms. This or that. Win or lose. The Beatles vs. Elvis Presley. Star Trek vs. Star Wars. Either-or.

Abrams don't play that game. The question, "Save or kill?" is too limited for him. He's too nice a guy, or at least that's what his public persona conveys, and so he can only answer demurely, "Save, save." If you reject the notion of that, you won't like Abrams because he's a remix artist who's taken up the self-appointed impossible mission of curating as many film franchises as he can. Remember, he's the one who got Ethan Hunt's adventures back on track in 2006. The Mission: Impossible franchise suffered from the sophomore slump but it's gotten progressively better since Abrams came on board (he's produced every installment since then, including the phenomenal Fallout.)

Look, I get it: people have valid complaints about the Star Trek reboot. The Abrams brand isn't everyone's cup of tea, but it knows that, don't you see? With its alternate-reality setup, the 2009 Trek bends over backwards to say, "Hey, this is its own thing." Unlike most reboots, it doesn't erase franchise history or pretend as though it never happened. Rather, it shows us a vision of alternate history, one where the characters, their connections, and their backstories are different, but the core of humanity is the same. This time, the "strange new world" explored, per the famous captain's speech, just so happens to be a different timeline: the Kelvin Timeline, as it's now known.

They're on a starship powered by a warp drive, but it's the sublime characters and the perpetual pep in their step that give this movie its tremendous propulsion through outer space. You'll never see as much sprinting, relentless running, Tom-Cruise-level running, on board the Enterprise as you'll see in this movie. That's its M.O: it's the running Star Trek movie (not to be confused with that other one we've referenced, the motorcycling Star Trek movie).

If you think Gene Roddenberry is rolling over in his grave at the state of Star Trek post-2009, well, maybe you're right. Maybe you know him better than I do. Then again, maybe Star Trek's creator wore a progressive outlook. It's like that scene in La-La Land where John Legend's character, the progressive one in the conversation, asks, "How are you going to be a revolutionary if you're such a traditionalist? You're holding onto the past, but jazz is about the future."

History might very well determine that Star Trek was J.J. Abrams' best film. You probably think I smoked some crack before typing that. I'm probably digging myself a hole with these kinds of loose-lipped, life-affirming, Trek-adoring statements ... but hear me out, one last time, as we near the end of this long love letter to the final frontier.

Star Trek was more of a sugar-rush shock to the system than The Force Awakens (which I love, by the way). It offered a fresher take, one less caged by reverence or rhyming with past episodes. While it may have strayed too far from the franchise's roots for the tastes of some, perhaps it is precisely "that instinct to leap without looking" (as Greenwood's Captain Pike would call it), that gives the movie such raw, unbridled kinetic energy.

Trek confession: I grew up thinking Star Trek meant The Next Generation. My first captain was Jean-Luc Picard. The Original Series was before my time. It was the stuff of old reruns. I was aware of it; I had watched some of the episodes and some of the later movies, but I had never gone back and watched the whole series until this film reboot set me down that path. Only then would I learn to luxuriate in all those early space-faring adventures, punctuated by Kirk's piercing eyes, Spock's inquisitive looks, and the romanticized faces of women in soft focus.

This movie made me rediscover my love of Star Trek and ultimately connect to the franchise in a deeper way than I ever had as a kid. I love it because of how it was so sure-handedly able to recapture the sense of wonder, the sense of pure exhilarating joy, that I felt as a kid watching movies. It beamed me back aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise, where I would stay for good this time. I know I can't be the only fan who had that kind of experience.

BLESSED ARE THE GEEKS

Star Trek began life as a cult phenomenon. This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the untimely cancellation of The Original Series. The show went off the air after a mere three seasons, only to find a second life in reruns. Despite its dated flourishes, it still holds up after all these years ... but now it's become something more, expanding into a thriving multimedia empire full of widely recognized pop-culture icons. Klingon is a legit language and the split-finger Vulcan salute is as good as International Sign Language.

Much has changed since the airing of that old Saturday Night Live sketch with Shatner at a Star Trek convention, telling a room full of geeks, "Get a life!" I don't know about you, Trekkers, but I always found that sketch to be funny and spot-on, an incisive little satire of geekdom. It hit close to home for me in a way that made me realize we probably shouldn't take any of this make-believe stuff too seriously. My favorite part — a bit that feels very 2019 — is how Shatner is forced to immediately retcon his own stage appearance, telling the assembled fanboys, "That speech was a recreation of the evil Captain Kirk."

A few years before he passed away, I once saw James Doohan, the original Scotty, in a basement convention hall in Manhattan, not that far from Rockafeller Center, where SNL is filmed. It was a far cry from Hall H at Comic-Con. That wasn't even a thing yet, because this was circa 2000-2001.

Somewhere along the way (the mid-to-late 2000s, by my estimate), geek became chic. In 2019, we're now apparently at peak geek, with Avengers: Endgame, the final season of Game of Thrones, and Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker all rolling over us the same year. To paraphrase an old biblical quote, "Blessed are the geeks: for they have inherited the earth."

Abrams' Star Trek is a fleet-footed, funny, at times fumbling expression of geek love for one of the most important media franchises on the planet. The beautiful people run ubiquitous through his film and television projects, and this one is no exception, but if you think of them as glamorous spokespersons for science, it's hard to fault them for baring their torsos. Kirk and Uhura parade around in their underwear, trading snappy patter because they're young and alive, as much so as Uhura's green-skinned roommate or the original Green Girl, Susan Oliver. That's the audience for this movie: people who are young, or young at heart, and maybe a little green, but most importantly, still alive and not so jaded that they're unable to enjoy the verve of the occasional ace summer blockbuster.

Star Trek wants the franchise out in the streets, not in some insular basement. Maybe, just maybe, what the series needed at this particular point in time was a non-fan, or casual fan — someone with an outsider's perspective like Abrams — to come in and shake it up, just to remind it that characters come first and big science fiction ideas are nothing without them.

That's a lesson the franchise seemingly learned between Star Trek: The Motion Picture and The Wrath of Khan. It's a lesson that's reinforced by the disparity between the pilot episode for The Original Series and its first few broadcast episodes. Compare the cast when it was only Pike and the pointy-eared Spock, surrounded by vanilla faces, to the cast when it was Nichelle Nichols and George Takei and all these other diverse actors.

What a difference a Deforest Kelley makes. In the first season premiere, "The Man Trap," Shatner and Kelley, the real McCoy, you might say, exude immediate charisma and chemistry with each other, and there's more of a personal stake in the plot for McCoy because it involves an old flame of his. The show came alive when it put its characters front and center and let the audience, too, have a personal stake in them. This film reboot is an electric reminder of that character-based approach to storytelling.

In 2009, J.J. Abrams and his cast and crew set out on a fun, freewheeling voyage. Their continuing mission over the course of two hours? To make people care about Star Trek again, so that it can "live long and prosper." Mission accomplished.