7 Things We Learned From The James Cameron MasterClass

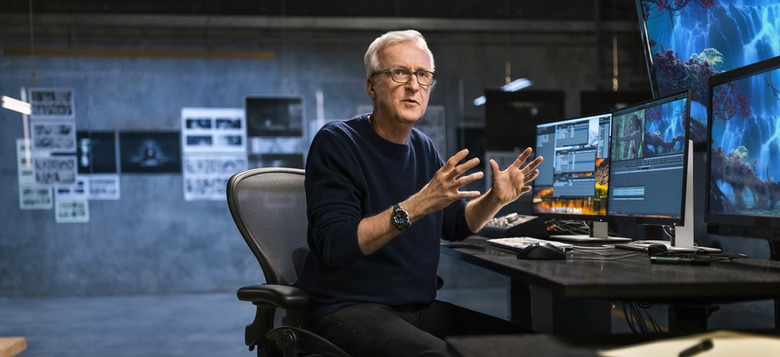

Legendary filmmaker James Cameron took a break from making his Avatar sequels to sit down for a new MasterClass on filmmaking, and the results are informative, engrossing, and insightful. Will watching the James Cameron MasterClass instantly turn you into a filmmaker? No, of course not. And if you know a lot about filmmaking to begin with, much of the information Cameron departs here will sound familiar. But Cameron is a gifted storyteller, and he's particularly adept at talking about himself and his work.

A master of technical craft, Cameron's focus through the 15 videos (which clock in at a 3 hours and 20 minutes in total) is primarily on how he learned skills along the way and adapted them as he evolved as a filmmaker. The MasterClass also finds the notoriously cranky director surprisingly reflective, even sounding a bit sheepish about his reputation as a hard-nosed taskmaster on set. These elements coalesce into a MasterClass that's definitely worth checking out if you're interested in Cameron's work, or in filmmaking in general.

Below I've broken down some lessons learned from Cameron's MasterClass. But this only scratches the surface – you'll need to subscribe to the class for the full picture.

Five Components to Making a Movie

When it comes to making movies, James Cameron has five specific components he considers to be key. They are:

Now that you've read that, you can officially go out and start making record-breaking blockbusters just like Jim Cameron! Okay, that's not true. But it's a start.

James Cameron: Origins

As the class kicks off, Cameron gives us his origin story – a quick crash course on how he went from a behind-the-scenes tech expert to a low-budget filmmaker to a full-fledged box office juggernaut. Cameron clearly likes to talk, and to talk about himself, but he doesn't come across as boorish or even haughty. He's actually quite pleasant to listen to.

As Cameron tells it, when he was a kid he watched the 1974 film Mysterious Island and was so inspired by what he saw that he went home and started drawing comic books about the film. But he would change the story, making up his own along the way. He was inadvertently "doing all the things a filmmaker does," but "graphically on paper." However, he didn't quite make the connection that he could apply this to making movies.

That changed when he saw Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Cameron went into the flick expecting just another space movie and ended up leaving the theater puking. His sudden projectile vomit wasn't because he hated the movie. Instead, the film's now-iconic stargate sequence made Cameron feel like he'd never felt watching a movie before. It was, he says, the first time he realized a movie could be a piece of art.

2001 had a companion book all about the making of the film, and Cameron picked it up and studied it. And while he didn't understand everything in the book, he started taking notes, and eventually picked up his father's Super 8 camera. And thus a filmmaker was born.

Somebody Has to Write a Story

"Somebody has got to write a story at some point," Cameron tells us. It seems obvious, but it's a fact that you can't shrug off. If you're making a movie, you'd be wise to come up with a story for that movie. And even if a director doesn't write his or her own scripts, they should at the very least understand the writing process. That said, it's okay to be flexible. Cameron adds that thinking in terms of act breaks is helpful – but you don't need to stick rigidly to a three-act structure.

"None of my stuff ever fits the three-act structure," he says, but he also adds: "It's good to know the rules before you break them."

"If an idea won't go away, that's when it's worth making a movie about," Cameron says, reflecting that he gets a lot of his movie ideas from dreams. He once had a dream about a metal skeleton rising out of a fire, and that dream turned into The Terminator.

When it comes to storytelling, Cameron stresses that sometimes it's "okay for the audience to be ahead of you." Even if you have story elements that seem obvious, it doesn't mean they're bad. Indeed, it can be extra cathartic for the audience to predict what's going to happen – and then to see they were correct. In effect, it encourages the audience to participate in the film.

And not everything needs to come from the screenplay itself. As an example, Cameron mentions that in Aliens, the young girl Newt was introduced earlier, before her entire family got bumped off by Xenomorphs. But when it came time to edit the film, Cameron realized it would better to introduce Newt later, after she's suffered her trauma. He calls it an "unplanned introduction."

Creating Characters

If you're writing a story for a movie, that story needs characters. Duh. But how do you create memorable characters? "Give an average person an enormous problem," Cameron says. He also says it's okay to draw on classic archetypes. For instance, when writing The Terminator, he was thinking of a Virgin Mary archetype – the story of the mother of a great prophet. He took that and ran with it, drawing on elements from his own life (his first wife was a waitress at Bob's Big Boy, just like Sarah Connor in the movie).

"The whole point of storytelling is to live outside yourself, but there has to be some connection to yourself," says the filmmaker. And the character creation doesn't stop at the script. That's just the start. It's then up to the actor to take things further. Cameron recounts how he had Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet rehearse a scene from Titanic with modern-day language – saying things they would say at the time without being worried about historical context. Cameron then took footage of that rehearsal and rewrote the scene to both reflect how DiCaprio and Winslet played it while also making it more appropriate to the era the film was set.

"The most sacred part of the job is to help the actor achieve their best work," the director says. He also stresses that when he writes an antagonist, he works to make the antagonist a little quirky, and even humorous at times. It makes for a more interesting villain – someone we dislike while we also find them amusing.

The Art of Low-Budget Filmmaking

While Cameron is known for his big-budget blockbusters, he came from humble origins. His career in film began with working with B-movie legend Roger Corman. And before he made The Terminator, Cameron directed the schlock sequel Piranha II: The Spawning (although it's worth noting that while Cameron is the credited director, producer Ovidio G. Assonitis shot most of that film). Even the first Terminator is a low-budget film, made for somewhere around $7 million.

But having a low budget needn't be a hindrance. In fact, Cameron says that as long as you prepare, you can make a low budget movie look great. "The art of low-budget filmmaking is the art of being thoroughly prepared and maximizing what you have," Cameron says. For his prep, Cameron – an accomplished artist – makes sure to storyboard everything. And when he wrote The Terminator, he made sure to write a script that featured affordable things to fit within the budget limitations.

You also need to be inventive. As an example, Cameron points out that they shot a lot of scenes for The Terminator near car lots, because car lots are usually brightly lit all night. By using this method, Cameron was able to light scenes without having to get expensive lights. He also points out that when it came time to make the film, he sat down with cinematographer Adam Greenburg and watched both Blade Runner and The Road Warrior. Cameron proceeded to tell Greenburg that he wanted The Terminator to look like someone put those two films in a blender.

If you're shooting with a low budget, you're almost guaranteed to not have a movie star in the film. But that's not a bad thing, either. As Cameron puts it, having a somewhat unknown actor in the lead actually forces the audience to pay more attention. If we're watching a Tom Cruise movie, we can generally guess how Tom Cruise is going to behave from scene to scene based on his previous performances. But if we're watching someone brand new to us, we might sit up and pay more attention in an attempt to figure out who the character is.

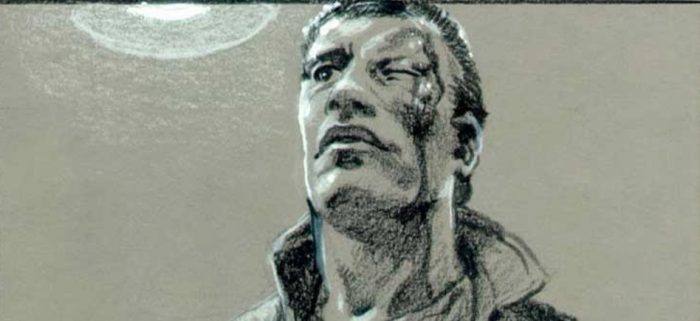

The low-budget talk continues into a breakdown of one of the Terminator effects scene – where a battle-damaged Arnold Schwarzenegger cuts his arm open to show his robot interior and removes a damaged eye in the process. The make-up work looks a little obvious today, but Cameron points out that when the film came out – 1984 – audiences weren't as well-versed in such effects work. Now, it's commonplace – and mostly done digitally. But once upon a time, stuff like this was fresh to audiences. And as a result, Cameron believes that audiences had a better grasp on the suspension of disbelief back then than they do now.

For another example of making the most of your budget, Cameron points to a scene from Aliens where Ripley confronts the alien queen in a nest full of facehugger eggs. While Aliens had a bigger budget than Terminator, Cameron points out that ideally, they would've had hundreds and hundreds of eggs in the shot. But they simply couldn't afford that – and made it work anyway, via editing. These days, such a trick could be pulled off digitally, but that wasn't an option at the time. "If you can't afford a digital extension of 100 eggs, make what you can and it'll work," Cameron says.

Crafting Set Pieces

Cameron is a master of set pieces, so of course, there's a video all about that here. It's better to have a few memorable set pieces rather than wall-to-wall stuff that will blow up your budget, Cameron stresses, going on to describe set pieces as "a film within a film."

"There are a lot of rules and advisories about why you put things in movies, and that they should all serve a purpose," Cameron says. "Except, they don't. Sometimes it should just be something you want to see as a filmmaker...and sometimes the only way to see it is to show it."

For example, Cameron uses a scene from Avatar as a set piece that got some studio pushback. The scene involves main character Jake Sully learning to fly a Mountain Banshee. The flying set-piece sequence goes on for a lengthy amount of time, and Cameron says someone urged him to cut it down because they felt it didn't add anything to the plot. But Cameron countered that he didn't care – he wanted to see it, and it stayed in the movie.

"If I want to see it, there are lots of people who are going to want to see it," Cameron reasons. "And they want to see it for itself, not because of a purpose. The purpose is to be present; to be in that world."

Reflection

"Curiosity is how you're going to find your stories," Cameron says near the end of the class. And such a statement leads the filmmaker into a surprisingly reflective period, although there are hints of that along the way. Early in the class, Cameron almost casually mentions that he considered filmmaking a "constant process of learning," and adds that he wishes he had learned leadership lessons earlier, specifically the importance of the role of leader of a group. "It's not a dictatorship, it's a collaborative medium," Cameron says.

The filmmaker has built up a reputation for being difficult to work for. "He is notorious on set for his uncompromising and dictatorial manner, as well as his flaming temper," wrote Andrew Gumbel of The Independent. Ed Harris, who worked with Cameron on The Abyss, was reportedly "so angered by the physical torment of the film and the autocratic ways of Mr. Cameron that he said he would refuse to help sell the picture."

To Cameron's credit, he doesn't try to defend any of his past antics or even downplay them. To be sure, he doesn't spend huge chunks of time dwelling on them. But he does say that if he could go back and do one thing differently in his career, it would be to improve the nature of the working relationships he had with his cast and crew members. "I could've listened more," he says. "I could've been less autocratic. I could've not made the movie more important than the human interaction of the crew." He even calls himself a "tinpot dictator." (I should also note that Cameron adds that he doesn't think of himself as cruel, just demanding.)

Cameron goes on to talk about how the ideal director, in terms of on-set behavior, is certified nice guy Ron Howard. There's a funny moment where Cameron mentions that he visited one of Howard's sets once and was "dumbfounded" at how much time Howard takes complimenting people on his set. And while Cameron and Howard are vastly different filmmakers, Cameron adds: "I aspire, even today, to try to be my inner Ron Howard."