Everything Or Nothing: What A James Bond Lawsuit Says About The Legacy Of The Franchise

Completion is often an important facet of one's fandom: you have all of The Beatles' studio albums on your iPod, or sitting on your shelf is every novel Virginia Woolf ever wrote, or you own multiple versions Cinema Paradiso. But what if you planned to have everything and you didn't get what you thought you were paying for?

That's the core issue of a class action lawsuit brought against MGM Studios and 20th Century Fox by plaintiff Mary Johnson of Washington, who bought the Bond 50: Celebrating Five Decades of Bond DVD box set, and filed the complaint when she realized the set did not include the 1967 film Casino Royale (the one with Woody Allen – yes, you read that correctly) and 1983's Never Say Never Again. It's a matter of whether this is necessarily false advertising, as there's legal precedent for why these films weren't included. But should these films be included in Bond box sets in the future? And do their very existence say about the 007 series in general?

A Brief History of Casino Royale '67

I'm still not quite sure if my Bond education was an unusual one, but I grew up understanding that the 1967 Casino Royale and Never Say Never Again were asterisks in James Bond history: films that weren't officially "canon" as it were, as they, formally, diverted from the conventions and tropes that had become an established part of the franchise. More logistically, they weren't produced by EON Productions, the company, started by producers Albert R. Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, that has made all of the James Bond films since the beginning, starting with 1962's Dr. No.

Ian Fleming, Bond's creator, had sold the rights to the first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1955 – an earlier rights deal to CBS resulted in the telefilm Casino Royale in 1954 as part of their Climax! series – to Gregory Ratoff, but the rights were then sold to Charles K. Feldman by Ratoff's widow, making it legally difficult for Broccoli and Saltzman to make their version of Casino Royale without Feldman as a creative partner and producer. Legal issues also halted them from making Thunderball as the first Bond film. They moved to adapt the sixth Bond novel instead, Dr. No.

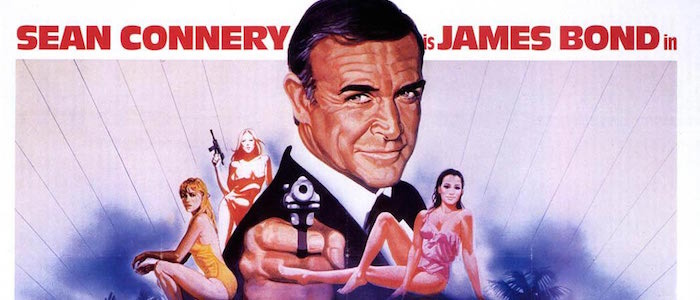

In years following the success of the James Bond series, two things occurred: many a knockoff and parody of 007 was produced and Feldman, who had worked on films like The Seven-Year Itch and What's New Pussycat?, still sought to make his adaptation of the first Bond book. The option to make a straight-up Bond movie was out of the question, partially because it didn't make sense to compete on the exact same turf and partially because getting Sean Connery (who had at that point a five film tenure as Bond) was a no go. Instead, he decided to make a Bond parody, with five directors (John Houston, Kenneth Hughes, Val Guest, Robert Parrish, and Joseph McGrath) and three writers (Wolf Mankowitz, John Law, and Michael Sayers), numerous contributors (including Billy Wilder and Ben Hecht), and an enormous cast including David Niven, Peter Sellers, Orson Welles, Deborah Kerr, and many Bond alumni like Ursula Andress, Vladek Sheybal, and Caroline Munroe. The movie is a mess. It is often rightfully acknowledged as such.

A Brief History of Never Say Never Again

The exclusion of Never Say Never Again also stems from legal issues, as Fleming had been working on a screenplay with Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham in the early 1960s, at that time titled Longitude 78 West. Fleming abandoned the script and turned it into the Bond novel Thunderball, published in 1961, without crediting either McClory or Whittingham. For this, breaching copyright, Fleming was taken to court, settling in 1963. EON made a deal with McClory, letting him produce Thunderball as a film in 1965, with no other adaptations of that book to be made for ten years following the film's release that year.

This gave time for McClory to stew, beginning work on another adaptation in the mid-1970s called Warhead, with Len Deighton and Sean Connery also working on the script. The film continued to be developed throughout the '70s, during which Roger Moore had taken over the "official" role of Bond, and EON continued to try to block it. Though Connery had declared he would never revisit the role of 007 again after Diamonds Are Forever in 1971, he would ultimately return for this film, which would finally get its release in 1983, with the title courtesy of Connery's wife, Micheline.

Distribution Issues

Both Casino Royale '67 and Never Say Never Again competed against EON-produced Bond movies the years they were released: You Only Live Twice and Octopussy, respectively. In the franchise's fifty-five year history, the baton of who owns the rights to finance and distribute the films has been passed several times. United Artists initially were the sole distributors until For Your Eyes Only in 1981, when MGM absorbed UA. MGM handled all of the Bond films by themselves from Tomorrow Never Dies in 1997 to Die Another Day in 2002. And MGM and Columbia Pictures have shared distribution rights since Casino Royale in 2006, with Columbia's parent company, Sony Pictures Entertainment, saving MGM from near bankruptcy in 2005. Currently, there's a bidding war over who will distribute the next Bond film, but it's much of these transferences of power which have kept the 1967 Casino Royale and Never Say Never Again from being included in box sets.

Both Casino Royale '67 and Never Say Never Again weren't distributed or produced by anyone that had ownership over Bond in the first place; the former was distributed by Columbia and the latter by Warner Bros. It wasn't until 1989 and 1997 that either film had its distribution rights purchased by MGM. An ongoing legal battle with the McClory estate, which prevented especially the latter film from being included in collected box sets, was settled in November 2013, too late for the release of the Bond 50 set in September 2012.

A Closer Look at Casino Royale '67

After all that history, should those two films ever be included in a set anyway? It's boring legalese you have to slog through to understand why they weren't included in the first place, but their legal precedents ended up shaping the very films themselves. It's crucial to Casino Royale '67's cinematic identity that the film satirizes the growing fanaticism surrounding the series and its devil-may-care attitude towards investing in ancillary products and a possibly questionable blueprint for how people should live their lives.

Casino Royale '67 looks and feels like it's been meddled with, like there have been dozens of hands making it. On the one hand, its incoherency doesn't make it necessarily more enjoyable than any other "official" Bond movie. And on the other, it may not make it any less enjoyable either. Since when did 007 movies have to make sense to be fun? That this film seems completely antithetical to any notion of auteurism suggests that there is no auteur of the James Bond movies except maybe the producers, which have strong-armed the series into a somewhat consistent and recognizable formula (one that has definitely seen a shake-up in the past decade).Casino Royale '67 doesn't resemble that formula in any discernible way, but it does lampoon it frequently. A severely concentrated adaptation of the novel, it follows many James Bonds and their inability to follow through on their mission (confuse the international crime syndicate SMERSH). It now now feels like a prescient comment on the very many James Bond actors that would come to define the icon's legacy and the careful calculation of lunacy in the James Bond world.

The strangeness of the film seems more affected when you place recognizable ideas of characters, or archetypes from the series, into more deliberately absurd situation. That none of the cast seems to be taking any of this very seriously is a tip off, they're invested in the idea of a comedic James Bond, but maybe not comedic James Bond in and of itself. Which is to say that the film's messiness is not its problem, but its wink. All tropes that were grafted onto the parody from the original Bond films are done so consciously, with a kind of meta self-awareness that's almost Brechtian. The James Bond films, however weird they may get from voodoo priests to invisible cars, are disinclined to wink at the audience. Because James Bond, both the character and the cultural entity, thinks he's cool. The James Bonds of Casino Royale '67 aren't kidding themselves.

A Closer Look at Never Say Never Again

In contrast to the oddball, mishmash of Casino Royale '67, Never Say Never Again is a pretty straightforward movie, carving itself out less as an explicitly James Bond film and as a marginally more generic action movie. It's odd to write that, given that Sean Connery has Bond in his blood and bones, but there seems to be an outward desire to distinguish this Bond in Never Say Never Again and the Bond he had played for the better part of a decade with EON. That it diverges from many of the Bond tropes, instead opting to be, essentially, a good spy thriller, is what makes Never Say Never Again work on its own terms. The best Bond films always did that, but with just enough to suggest a connective tissue or a shared history to give it the impression that this film was part of something bigger. That last part is what this film is missing.

Though Connery is quite good as an older and more mature 007 – there is a more tangible sense of mortality and danger here than in most of his Bond performances – and though Klaus Maria Brandauer makes for an entertaining villain, it doesn't feel much bigger than the context it has set for itself. Which is fine. It is, by all means, a passable movie, eliding most of what makes many James Bond movies plain, boring, and predictable. But a lot of the Bond films compensated for their predictability with a scale that existed outside of the film, though it seemed to be acknowledged to insiders within the movies themselves.

Defining the Bond Canon

For what it's worth, there's much writing on both Casino Royale '67 and Never Say Never Again in books about James Bond, such as License to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films by James Chapman, For His Eyes Only: The Women of James Bond edited by Lisa Funnell, TASCHEN's giant coffee table book The James Bond Archives edited by Paul Duncan, DK Publishing's James Bond: 50 Years of Movie Posters, and numerous others. It came as a deep shock to me to learn that others hadn't grown up with at least a peripheral knowledge of the legal battles that kept the two films from being "canon". But, then again, maybe I was more obsessive than most (owner of much Bond ephemera, but, ironically, not of these two films).

Perhaps one should consider what "canon" even means in the first place. That it follows some sort of established logic? Established by whom? Do the legal battles matter if you weren't a part of them anyways? I have rarely been attached to the concept of canon, as I often find the justifications for what is or is not canon somewhat arbitrary. Art, in any context, is recycled and reused and James Bond in any form has, until the Daniel Craig cycle, always had an anthological structure with almost nothing connecting one film to another besides the presence of SPECTRE or an offhanded remark about a character no one remembers. To me, canon is a box someone tells you to use even though there's no advantage to using it other than an illusory sense of organization or linearity.

Those concepts, however, were never of concern for the Bond franchise. The only indication of consistence was a formula, and formula in and of itself doesn't feel sturdy enough to suggest anything in the series is canon. But that isn't to say that the officially EON-produced films don't have a very specific sensibility about them, which essentially is what makes Bond so appealing and so worthy of a legacy in the first place. The films fluctuate in quality, and its formula rarely is undermined, but they're so self-assured and their protagonist so outsized that he can be both malleable and rigidly archetypal – that there can be no other James Bond and that makes it clear that nobody can do it better. Thus, Casino Royale '67 and Never Say Never Again, regardless of how good or bad they are, can't help but feel, to some degree, like they're trying to imitate and emulate an indescribable cinematic power.

Sure, Casino Royale '67 and Never Say Never Again could be included in box sets, but only under the condition that they're included with asterisks. Not merely because they're "not James Bond movies" in an elitist way, but that the legal precedents that informed their very delayed creation shaped their existence, and that the films and their style are made in contrast to the ways the EON-produced ones are. That they had to exist outside of the EON norm is what makes them interesting, at the very least within the context of film history and James Bond history. So, absolutely include the two films in a set celebrating all of Bond history – just makes sure you include the telefilm of Casino Royale and some liner notes examining their places in Bond history, too.