How Nope Relates To Us And Get Out

Warning: This article contains major spoilers for Jordan Peele's "Nope."

Jordan Peele is the kind of filmmaker who loves melding ambitious ideas into a full-blown spectacle. When the first trailer for "Nope" dropped, critics and fans excitedly speculated which horror subgenre he'd be tackling next. To his credit, Peele makes it a point in his work to examine why audiences are so intrigued to watch his films that, for the most part, center on trauma as entertainment. Sure, there are harrowingly fun set-pieces — like a house dripping in blood or the hauntingly endless Sunken Place or serial-killing body doubles. But these horror elements are used to confront and voice socio-cultural concerns.

When Rod Williams stepped out of a cop car at the end of "Get Out," audiences sighed with relief, confronting the often under-discussed assumption that police officers commit anti-Black violence. Adelaide's escape to freedom by murdering Red in "Us" was an allegory to the sweeping brutality of capitalism, a system where only some humans live well thanks to others' suffering. Semester-length college classes revolve around Peele's work, so it's no easy task for one essay to dissect the connective tissues at the heart of Peele's filmography. However, there are some resonant themes in "Nope" that Peele fans will recognize. Similar to his prior films, Peele's sci-fi-Western "Nope" explores many tough questions, including: Whose histories do people choose to forget and why? And, as importantly, who pays the cost for that ignorance?

Reimagining U.S. history to highlight inequity

Jordan Peele's "Us" used the 1986 Hands Across America fundraiser to critique how American capitalism attempts to solve complex social issues like homelessness by throwing money and spectacle at it. Like in "Us," the campaign featuring celebrity singers like Michael Jackson didn't solve homelessness. Of the $34 million raised, only $15 million went to charities that mostly used donations for operational costs. In 1986, The New York Times estimated a missing $7 to $8 million from pledges. The homeless and the Tethered suffered due to systemic failures.

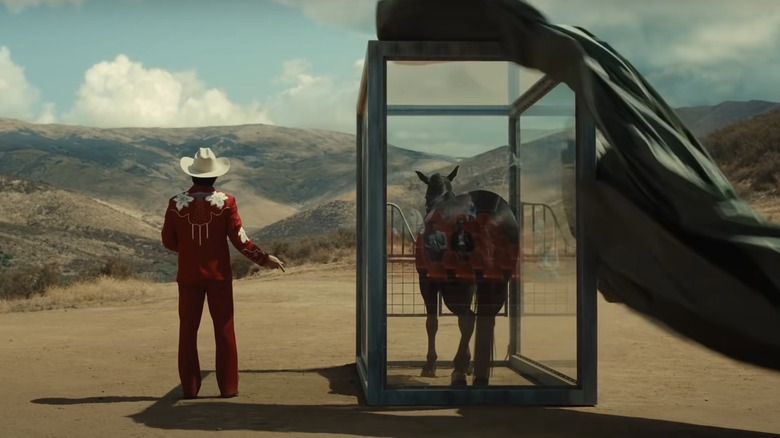

"Nope" fittingly includes a "Buck and the Preacher" movie poster early on, reminding audiences of Sidney Poitier's directorial debut and Black-westerns' legacy. But Peele's most notable historic reimagining to highlight inequity comes from a forgotten Hollywood legend. Many know Eadweard Muybridge's "The Horse in Motion" as the world's first film, but there's never been documentation on its leads. The identities of the two Black jockeys, Hollywood's first film actors, are unknown, although it's theorized one is named Gilbert Domm.

Peele reimagines this truth in "Nope," giving the Haywood family a storied ancestry: they're the only Black horse trainers in Hollywood and descendants of cinema's first star. "Nope" deepens this connection by showing how a fictional film crew disregards OJ and Emerald when they're on set. They're not treated as an integral part of the production or like Hollywood royalty. They're ignored, suggesting not much has changed since 1878. As of 2022, film studio CEOs are 91% white and frustratingly lack Black executives.

Black artists' work is valued more than the artist

Jordan Peele's three films center on undervalued Black artists using their work to save themselves. In "Us," the only thing that saved Red from the Tethered was her ability to dance, awakening life in them and herself. To escape the Armitage family in "Get Out," Chris uses his camera to stun the sunken individuals from attacking him. In "Nope," the only reason OJ survives the territorial UFO is by applying his animal training knowledge to the predator's hunting patterns. OJ, Chris, and Red go through horrific experiences that they never asked to happen nor did they directly cause. But time and time again, art saves Peele's characters from a more tragic fate.

His films don't shy away from showing others' exploiting Blackness and disrespecting Black creators, like how Chris' eyes were supposed to go to the blind Jim Hudson so he could create art in "Get Out," or how the fictional directors in "Nope" want OJ's trained horse but not his advice. OJ Haywood gets fired from a film set for doing his job correctly; by the end of "Nope," he's the only one who can outrun an alien. Peele's horror films highlight art's life-saving potential for his Black characters who always deserved more than the abuse they received.

How capitalism breeds self-serving individuals

"Us," "Get Out," and "Nope" all have different interpretations of who the other is. The other (or the marginalized) in Jordan Peele's work is rightfully skeptical about who to trust as their survival depends on it. In "Get Out," a film specifically about racial dynamics, Chris and the Black sunken individuals are the others who are fighting to escape a white family's abuse. In "Us," the others are the Tethered, a multi-ethnic nation of soulless clones hidden underground by governmental forces, seeking to kill their counterparts so that they can live a full life. Since his films are grounded in reality, his characters also subtly contend with confronting how their income, ethnicity, skin color, and sexuality affect their fate.

Throughout Peele's latest horror film, "Nope," the other is a trickier concept to unravel. Seemingly, the alien is the other, but it's unclear exactly when (and for how long) this alien has been on Earth. The alien only eats and hides — as a predator does — whereas the humans are the ones luring it out to capture its image and use it for their financial gain. Jupe arrogantly thinks he can train the UFO to work for him by feeding him OJ's horses as bait while a crowd watches. In response, the UFO swallows everyone at the ranch. "Nope" feels like it's commenting more on how capitalism creates humans who manipulate others for their fiscal benefit, similar to "Us" and "Get Out," despite the murderous cost.

The evil of colonialism

There are plenty of interpretations out there on what the alien in Jordan Peele's "Nope" represents. If a viewer believes this alien is a new arrival to Earth, then there's a lot of meat to the idea that it represents the all-consuming evil of American colonialism. In certain shots, the alien balloons in a way that looks like white European sails on the high seas. Historically, American colonizers have taken up resources, destroyed lands, and valued their survival over Indigenous cultures. Throughout "Nope," the alien discards what it can't use and feeds on anyone who threatens it. In that light, there's certainly a settler-colonizer relationship with the Haywood family. (For those curious to dig more into this theme, Dr. Kali Simmons has a fantastic lecture on how Indigenous-created horror has tackled similar stories.)

"Get Out" explored a similar concept through a sci-fi lens. Peele's 2017 film revolves around a white and wealthy family enslaving Black people by suppressing their minds. They do this so they can live longer, even if it sacrifices Black lives. Peele used "Get Out" to illustrate the remaining roots of America's slave-based economy that are exposed in the film as microaggressions and problematic thought patterns that eventually lead to a new form of slavery. Despite being about 200 years since slavery ended in the U.S., "Get Out" warns that racist thoughts — like seeing Black people as tools for entertainment or labor — need to be eradicated before they grow into harmful systems.

What's the cost of success in America?

The saddest aspect of "Us" is how it pits Red against Adelaide to discuss class warfare. Red's dream of becoming a dancer was stolen by Adelaide. Adelaide grew up in such an oppressive setting that she felt murdering Red was her only chance to escape the Tethered's dismal fate. Jordan Peele's 2019 film digs deeply into the cost of obtaining a certain social status. Although Peele crafts some pointed jokes about wealth in Dahlia's obsession with facial surgery, it's clear what the message of the film is: for everything received, there's a cost. The easiest access comes, the more that someone else is working to make that happen.

In "Nope," money is a source of frustration for OJ, Emerald, and Ricky, aka Jupe. Hollywood jobs are slim, so the Haywood family sells their horses to Jupe to stay afloat. OJ and Emerald fight because OJ believes Emerald is hustling too hard, whereas Emerald thinks OJ isn't trying hard enough. Jupe is afraid he needs to go bigger and better to attract more customers to his half-filled ranch. Sadly, the alien arrival only further highlights these tensions. The siblings risk their lives for the "Oprah shot." Jupe feeds Haywoods' horses to the alien in hopes that he can train the predator to become a part of his tourist spot attraction. The promise of a financial windfall outweighs anyone's need for self-preservation, leading to Jupe's and (arguably) OJ's death.

Examining America's addiction to spectacle

Jordan Peele's "Nope" had a $68 million budget, far out-weighing the $4.5 million budget of "Get Out" and the $20 million budget for "Us." Given those resources, Peele invested a lot into the film's cinematic scale. He hired cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema, of "Dunkirk" and "Interstellar" fame, to capture the film's cosmic skyscape. "The beauty of the sky is enthralling — the first movies, in a way," Peele told AP. "Every now and then you'll see a cloud that sits alone and is too low, and it gives me this vertigo and this sense of Presence."

Peele used the film's lush visuals to examine humans' attraction to spectacle. "Attention can be a violent thing and our addiction to spectacle can have negative consequences," he said, also adding: "I think sometimes if we give the wrong spectacle too much attention, it can give it too much power." The hungrier the Haywoods get to capture the alien's image, the closer to danger they become. By the end of "Nope," the alien consumes all of OJ and Emerald's time. Characters consistently look up in the film, presenting a compelling visual metaphor for aspirational wealth. People want the notoriety of capturing the alien's image regardless of the cost. Like "Us," Peele uses the dramatic "monster" reveal to draw people's attention to what they value and why. Those obsessed with obtaining more are consumed (literally) by it.

America's monetization of spectacle

"Nope" began as Jordan Peele's desire to "create a spectacle," a movie that would draw audiences back into theaters to witness for themselves. While working on his "great American UFO story," Peele wanted to address the good and bad that comes along with "this idea of attention," beyond his film just being a sci-fi/horror epic. OJ and Emerald's quest to get the "Oprah-shot" works well as a metaphor for the entertainment industry's ever-growing obsession with over-the-top spectacle. In the same year that Netflix allotted reportedly $30 million per episode of the second to last season of "Stranger Things," the company also laid off workers from Tudum, its new fan-focused entertainment website that hired mostly POC writers with the promise of higher wages, only after five months of operation. Again, there's a cost for everything grand if you look for it.

"If we are obsessed with the wrong spectacle, it can distract us from what's really going on," Jordan Peele told AP. "There's really a human need to see the unseeable that our entire society is based around. And in so many ways we see it. The last five years, it feels like we've gone from seeking spectacle to being inundated with it." In an interview with Empire, Peele discussed the "toxic nature of attention and the insidiousness of our human addiction to spectacle." In "Nope," the characters are confused if the alien's eye is also its mouth. Metaphorically, it reads best if a viewer sees it as both. Spectacles thrive on attention. The more attention they receive, the larger they grow. "Nope" reminds audiences that giving attention to spectacle is a choice as is overlooking (like Adelaide in "Us") the financial hardship it brings others.

Exploring trauma as entertainment

Like most horror films, the characters in Jordan Peele's films never have it easy. They've narrowly escaped a Stepford Wives-like experiment, murderous clones, and a carnivorous alien. When asked about the characters' fates in "Nope," Peele dug into his view of why audiences watch films with harrowing stakes to IndieWire: "When you're on a road, and there's an accident, [and people stop to watch], what you're talking about [is] trauma as entertainment. It's intrinsic enough in our DNA that traffic slows down when there's a spectacle to be seen, a bad spectacle ... Everyone likes some form of horror or darkness."

"We need it," Peele added. "We need to contend with these things, whether it's coming to see my movies or your procedural television that just goes to the darkest place of all time every night, but somehow you go to sleep OK. We need this. Horror [films] and the people who try to capture their nightmares and show it, I have to think and hope that it provides some catharsis for some people."

Daniel Kaluuya's role in the film

Like the critically beloved "Get Out," "Nope" also stars Daniel Kaluuya in a leading role. While "Get Out" was more about Chris' journey to finding freedom from the Armitage family, OJ's journey revolves around healing the fractured bond with his sister Emerald. Kaluuya plays OJ as a wearied and tired horse trainer who is skeptical of any get-quick money scheme, and almost all of the side-financial-hustles that Emerald has going on in her life. However, he eventually decides to help Emerald with capturing the image of the alien.

At times, it seems like he's doing it to save his family's failing ranch. At other times, it feels like he's alien-hunting to secure Emerald's financial future. No matter his motivation, OJ is selfless and deeply compassionate under his gruff exterior, not unlike a modernized cowboy. When asked about OJ's relationship with Emerald, portrayed by a pitch-perfect Keke Palmer, Kaluuya told Variety, "That brother-sister narrative, I feel was a really unique arc in modern cinema. You don't really see narratives like that, we call it 'siblance.' Just two people who love each other, but really annoy each other. That's natural and people identify with that."

Who does the most amount of labor and why?

Jordan Peele's films love to focus on work, specifically digging into the division and equity of labor. In "Get Out," the inequity is very clear as the Armitage family enslaved Black individuals to do their domestic work. Within "Us," the Tethered technically experience the work their counterparts do, but without seeing any benefits. "Nope" also examines who is doing the most work and why on so many intriguing levels. There's Jupe's tourist-trap ranch that makes money off of Haywood's horses that OJ trained. There are the horses who, for the most part, are treated fairly — until they're left at the ranch to be alien fodder. But the film's best representation of unfair labor practices is found in Gordy's heartbreaking storyline.

In the film's fictional sitcom, "Gordy's Home," a trained chimpanzee named Gordy goes on a massacre due to a popped balloon. Gordy had no idea the alarming sound wasn't something sinister and kills and maims his co-stars, thinking he needs to defend himself. Despite being a commercial asset for years, the set had no safety measures in place for Gordy's triggering event. Gordy is soon killed after the massacre. Hauntingly, this scene asks a lot of questions about what use a company has for workers. What happens when a worker is no longer of use to a company? What measures are in place to support a worker's health, including that of a young and traumatized Jupe who survived the events?