Tales From The Box Office: Toy Story Launched One Of Cinema's Most Reliable Hit-Makers

It is easy to take computer animation for granted in the modern era. Technology has come such a long way, to the point where many YouTubers with virtually no money can create impressive animation just for the fun of it. Yet, in the mid-'90s, this was far from the case. "Jurassic Park" had pioneered the use of computer-generated visual effects in blockbusters in 1993 but it had to be used very sparingly — and in concert with some of the best practical effects ever put to screen — to truly work. But making an entire 3D computer-animated film? That was a radical idea. But it was one that Pixar was bold enough to try with 1995's landmark "Toy Story."

Despite being a gigantic risk, released by Disney, the film was a gigantic success and paved the way for a new era of animated cinema. And, while many other studios would have success in this arena in the years to come, Pixar remains the king of the hill with a record of hits to its name the likes of which few other studios have ever achieved. It all started with Buzz, Woody, and a radical idea.

In honor of the release of Pixar's latest "Lightyear," marking the studio's return to theaters after more than two years thanks to the pandemic, we're going to look back at "Toy Story," how it came to be, how it set Pixar on the path to record-breaking success, and what lessons modern Hollywood might be able to extract from it. Let's dive in, shall we?

The movie: Toy Story

It is worth acknowledging before digging into this that John Lasseter, the director of "Toy Story" and one of the key figures within the Pixar ranks for decades, has since become a controversial figure. After mounting accusations of inappropriate behavior behind the scenes during his years at Disney, Lasseter left the company and now has a gig at Skydance. That said, you can't tell the story of this movie or Pixar's success without Lasseter. It's just the truth of the matter.

For years, Lasseter wanted to make a full, computer-animated movie and had even brought the idea to Disney long before "Toy Story" ever came to be. They rejected him, and so he took his business elsewhere. Namely: Pixar, which at that time had Apple dounder Steve Jobs as a majority stakeholder. However, when Lasseter's short "Tin Toy" won the Oscar for Best Animated Short Film in 1989, that managed to get the attention of Disney execs. As the filmmaker explained in 2015, it was actually Tim Burton who managed to get the ball rolling in a roundabout way.

"Disney kept trying to hire me back after each of the short films I had made. I kept saying, 'Let me make a film for you up here [at Pixar]'. It always said, 'No, a Disney animated film will always be made at Disney.' It had no interest in doing an outside project. What changed their mind was Tim Burton. Tim and I went to college together and he had developed a feature idea [while employed by Disney] called 'The Nightmare Before Christmas.' He went on to become a successful live-action director and was trying to buy 'Nightmare' back from Disney. And it said, 'Why don't you just make it for us?' That opened the door for Disney to think of these 'niche' animated films that could be done."

Indeed, up until that point, Disney was militant about doing things in-house. But they wanted Lasseter, and Burton's "Nightmare Before Christmas" proved that partnering with outside companies could work. So it came to pass that Pixar would produce a feature-length, fully computer-animated film for Disney, becoming the first of its kind.

Toys and the trouble with humans

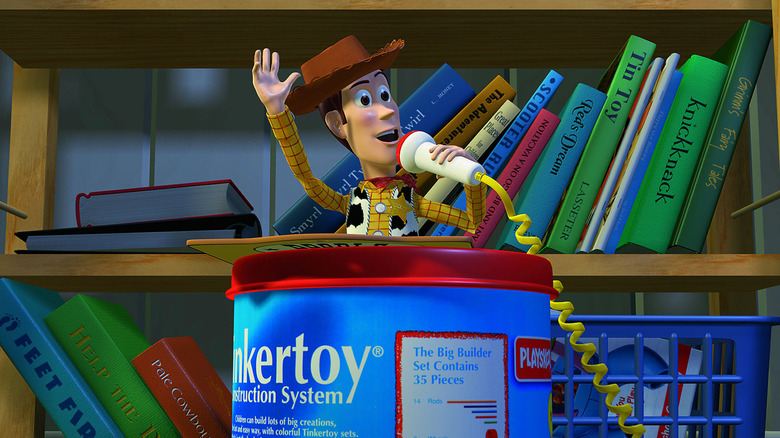

Honestly, "Toy Story" looks a little crude by today's standards, but it simply cannot be overstated just how revolutionary it was at the time. But as brilliant as the concept was, it came about as a result of the limitations of the time. In that same retrospective piece from 2015, Lasseter also explained that making toys the main characters had to do with the fact that humans were incredibly difficult to accomplish at the time.

"We knew what computer animation could do. What its strengths were. And we knew what it couldn't do. Everything tended to look like plastic. So why not have the main characters made of plastic? Having toys as characters really lent itself. Humans were by far the most difficult to create, so we told the story from the toys' point of view."

There's a good reason we don't see too many people from the knee up in "Toy Story" and, when we do, it's mostly the terrible-looking Sid. A grueling production process followed, as did an equally complex casting process, with Tom Hanks ultimately leading the way as Woody and Tim Allen voicing Buzz Lightyear. But, after years of rewrites, development, innovation, and uncertainty, the lean 81-minute movie arrived in theaters. Animation would never be the same again.

The financial journey

Debuting in theaters on November 22, 1995, "Toy Story" had a full five days with the Thanksgiving holiday, and that served the movie well. It took in $39 million, easily besting the likes of "GoldenEye" and "Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls." That set it up for one hell of a run, with Pixar's then-experimental 3D animated feature taking in $192.5 million domestically and $172.7 million internationally to date, giving it $365.2 million against a reported $30 million production budget. For those who are keeping score, that's a full 12.2 times its budget.

But this was merely the beginning of a much longer, larger financial journey. Pixar, up through 2020 when the pandemic kneecapped the industry, had a string of successes the likes of which few studios could ever hope to achieve. Through 25 features (with "Lightyear" counting as its 26th), Pixar has earned a staggering $14.7 billion, unadjusted for inflation. Only six of those films have fallen short of the $500 million mark worldwide (save for the ones released directly to Disney), and one of them was "Onward" which had its theatrical run cut very short by the pandemic. Otherwise, it certainly would have been another winner.

Pixar became a brand that moviegoers of all sorts trusted implicitly, be it with a sequel such as "Toy Story 2" or a pretty radical original idea such as "Inside Out," even extending to an ambitious sci-fi film such as "WALL-E." Pixar simply doesn't miss. That's why Disney finally said screw it and bought the company for $7.4 billion in 2006. All of that insane success, all of those untold billions, all stemming from an 81-minute movie about toys coming to life.

The lessons contained within

For me, this is one gigantic lesson sitting here and it is aimed squarely at Disney. Understandably, Disney had to do what it had to do to survive during the pandemic. They released "Onward" on Disney+ because theaters weren't open and it was a nice thing to do at the time. After suffering multiple delays, they opted to do the same with "Soul" at the end of 2020, before vaccines really kicked in and the future was still largely uncertain. But "Luca" and "Turning Red," two important original films hailing from Pixar, didn't feel like they needed to be dumped to streaming, yet they were anyhow, and that is the real thing to focus on here.

In a franchise-obsessed version of Hollywood, Pixar was one of the last bastions of original cinema, with movies like "Coco" managing to become gigantic breakout hits in recent years. As we've seen with movies like "Everything Everywhere All At Once," quality is a bigger indicator of what brings people out to theaters these days, not so much branding. But the Pixar brand is still (or perhaps was) stronger than ever. That, coupled with a great original concept, could seemingly still benefit theaters and artistic expression alike. By no fault of "Lightyear," it feels like a bit of a shame that a "Toy Story" spin-off is the movie bringing Pixar back to theaters when several originals were offered up for free on Disney+. Meanwhile, people had to pay $30 to watch "Black Widow" and "Mulan" through Disney+ Premier Access.

In the process, Disney may well have undercut the perceived value of Pixar, with consumers perhaps viewing these movies as streaming concerns now, rather than something that demands to be seen in a theater. Regardless of what happens with "Lightyear," Disney would do well to try and ensure that Pixar has a theatrically viable future and not just be content to dump the next potential big, original breakout hit to Disney+. Cinema needs Pixar perhaps now more than ever.