Orson Welles' Directed Films Ranked Worst To Best

Surveying Welles' filmography as a whole, some trends emerge. It's easy to see that Welles was a fan of Shakespeare, particularly the Bard's characters who author their own undoing. Whenever Welles portrays relationships, his characters evince betrayal, hypocrisy, and deception. He returns to the turn of the 19th into the 20th century repeatedly, an unexpectedly early era for a man born in 1915.

He was also remarkably prolific. Even after winnowing his filmography down to the projects he directed, this article doesn't have room to consider all the short films and television productions Welles made, nor all the feature films he directed that never saw completion. In addition, while it might seem ironic given Welles' conflicted feelings about authorial attribution, I've separated out films directed by Welles that were decisively completed by other hands (to a larger degree than regular studio interference) by placing them lower on this list.

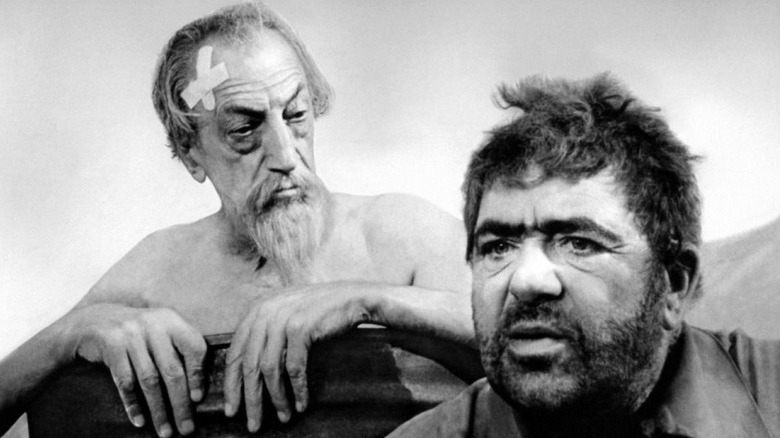

15. Don Quixote de Orson Welles

Stop me if you've heard this one before: Orson Welles had a brilliant idea, but it fell into other hands, then fell apart.

The novel conceit behind Welles' attempted adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes' novel "Don Quixote" was to bring the characters of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza into the modern day, since they were intended to be anachronisms even when Cervantes first published his novel in the early 1600s. Welles filmed test footage for "Don Quixote" as early as 1955, and second-unit photography as late as 1972, so he was in no hurry to complete this project, which he tinkered with until his death in 1985.

When Jesús Franco, who'd served as Welles' second-unit director on "Chimes at Midnight," released a "completed" version of the film in 1992, the disparity in the levels of quality of Welles' footage over the decades made its patchwork origins all too obvious. Only the scenes of Sancho Panza navigating a modern carnival and delighting neighborhood children with his dancing are at all watchable. Not recommended for anyone outside of die-hard historians.

14. Mr. Arkadin

Nearly half a dozen edits of "Mr. Arkadin" were released during Welles' lifetime, but the Criterion edit of 2006 arguably comes closest to capturing his intent. It was worth the effort, because "Mr. Arkadin" spins a world-spanning mystery about a self-made man's need to conceal the nefarious backstory behind his fortune, with every step closer to the truth plunging our point-of-view investigator that much deeper into trouble.

As much as revealing Gregory Arkadin's disreputable connections and misdeeds might inconvenience his mutually beneficial dealings with polite society, Arkadin is driven more fiercely by his fears of losing the love of his good-hearted daughter Raina. Welles crafts both a compellingly overpowering persona in the globe-bestriding titan of industry and a precisely paced plot that allows both the film's narrator and audiences to realize the existential level of peril our protagonist is in.

Credit to Welles' former protégé, "The Last Picture Show" director Peter Bogdanovich, for contributing to the cohesion of the Criterion edit.

13. The Other Side of the Wind

Bogdanovich also contributed to the completion of "The Other Side of the Wind," which would rank as one of Welles' best works if he'd been able to release the final cut himself.

Welles was on the edge of capturing 21st-century storytelling and media, constructing a highly improvised film-within-a-film narrative about a tyrannical director in decline and his final unfinished feature, using the premise of his poorly organized birthday party to assemble a fictional documentary out of "found footage" supposedly shot by other filmmakers in attendance. By casting John Huston as his half-mad, Zeus-like sky-father of an aging director, Welles sent up the self-styled machismo of old-school storytellers like Ernest Hemingway. By casting Bogdanovich as Huston's protégé, Orson exposed the codependent dynamic of his emotionally fraught relationship with Peter in real life.

The disjointed clips we see from the film-within-the-film, also named "The Other Side of the Wind," come across as an old dog director's attempts to emulate the tricks of the "New Wave" movement, with visually striking isolated scenes adding up to an incoherent (intentionally, on Welles' part) parody of contemporary arthouse cinema.

12. Journey into Fear

Welles was originally set to direct "Journey into Fear," and contributed to both its script and its casting, but his work on "The Magnificent Ambersons" forced him to step aside for Norman Foster to assume directing duties. The end result is a nifty Hitchcock-esque World War II-era espionage caper that's more clever than meaningful, with a tendency to telegraph its plot twists, except when employing questionably-merited tropes such as a misleading framing sequence.

Joseph Cotten again earns audiences' sympathies by playing one of fate's patsies, and the film rolls forward with the terrible, relentless momentum of that one bad day that never ends. It's solidly okay as Welles-lite fare, but it's hard not to notice that Orson as Col. Haki, head of the Turkish secret police, resembles a Joseph Stalin impression by way of Zsa Zsa Gábor, complete with silly hat; similarly, Dolores del Río's stage outfit appears to be lifted straight from the Cheetah in the Golden Age Wonder Woman comics.

11. The Immortal Story

Based on a short story from the 1958 collection "Anecdotes of Destiny" by Danish writer Karen Blixen (aka Isak Dinesen), Welles planned for "The Immortal Story" to be released as a two-part anthology film, with the second half based on Blixen's "The Deluge at Norderney." As often happened with Welles' productions, things fell apart.

Welles trimmed his film down to a Bonsai-like tragedy in miniature, telling the story of a materially wealthy man as trapped by the limits of his imagination as by the debilitating physical conditions of his age. Mr. Clay, a merchant living alone in 19th-century Macao with only his studious bookkeeper to keep him company, is so literal-minded and devoid of more meaningful pursuits that he insists upon making an apocryphal sailors' tale come true. While his transgressions against his former business partner and the man's daughter unquestionably qualify as villainous, Welles paints Clay as a figure to be pitied, regardless of how little he merits our sympathies.

10. The Trial

In adapting Franz Kafka's early 20th-century novel of the same name, Welles' revisions of the source text result in a film that feels ironically more authentic to the writing that inspired it. While Kafka wrote "The Trial" between 1914 and 1915, Welles reflects two major developments of the post-war 20th century by adding a room-sized UNIVAC-style computer to the workplace of accused office worker Josef K., who's executed not by a knife, as in the novel, but with a dynamite blast that forms a mushroom cloud, echoing a nuclear explosion.

Even as Welles retained the wrong-side-of-the-Iron-Curtain political flavor of Kafka's novel by filming much of it in Yugoslavia, he made the tale's setting nebulous by casting the all-American Anthony Perkins as our persecuted protagonist Josef K. Having actors with New York and California accents deliver lines from absurdist eastern European literature makes their gaslighting dialogue sound a lot like the laugh-track exchanges of "Seinfeld." Welles even told Perkins to treat "The Trial" like a black comedy, although the extended scenes of Josef K. seeking to escape the halls of government, whose ill-defined boundaries seem ever-present, are stifling enough to make me physically queasy.

9. Macbeth

If Welles had filmed his legendary "Voodoo Macbeth" stage adaptation for the Federal Theatre Project in New York in 1936, I'd likely rank it higher on this list, but even with a tight production schedule and a paltry budget working against him, Welles summoned up an innovative, uniquely cinematic take on "Macbeth" for Republic Pictures in 1948. Welles adds scenes with the witches, arming them with a clay figurine of Macbeth upon which they cast spells like a voodoo doll, and the Thane of Cawdor's execution takes place on screen, as does Lady Macbeth's suicide and the battle between the forces of Macbeth and Macduff.

Even the crudity of the film's sets, leftovers from Republic's westerns, suited Welles' stated intent that the film's setting should be "a perfect cross between Wuthering Heights and Bride of Frankenstein," since the swirling mists and rough-hewn appearance of Macbeth's castle make it appear barely ascended from a subterranean Hell. Welles makes Macbeth's traumatized guilt agonizing to behold, even (especially) in silence, and his cast includes a pipsqueak-voiced Roddy McDowall as Malcolm, and future Irish genre villain Dan O'Herlihy in his first American film role as Macduff.

8. Othello and Filming Othello

Given Welles' empathy for oppressed minorities, it's no surprise that he performed Shylock's monologue from "The Merchant of Venice" on "The Dean Martin Show" in 1968, nor that his 1951 film adaptation of "Othello" showed such sympathy for its title character, whom Welles portrayed as an outsider in Venetian society even beyond his Moorish heritage.

"Filming Othello" was recorded roughly a quarter-century after "Othello," but it's worth watching both films, not only for Welles' insights into the characters and their dynamics, but also to appreciate how Welles (unlike Jesús Franco) weaved together footage filmed years apart so well that the edited film plays as a seamless whole.

Welles achieved authenticity in "Othello" by using whatever settings were available, leading to Roderigo's murder unfolding in a Turkish bathhouse, a departure from Shakespeare's text, while also reflecting the deterioration of Othello's outlook by shooting the film's settings as progressively more encroaching and claustrophobic. And Welles invited his "Othello" costars Micheál Mac Liammóir (Iago) and Hilton Edwards (Brabantio) to dialogue over dinner in "Finding Othello," as they considered the intersections of tragedy and gender roles, with interpretations ranging from antiquated to avant-garde.

7. The Stranger

Few settings feel as safe and cozy as a small town in New England in the fall, just as the leaves are starting to turn. Welles successfully weaponized this comfortably folksy atmosphere in "The Stranger" by dropping a fugitive Nazi war criminal into the trusting fictional community of Harper, Connecticut and having him hide in plain sight, not only as a beloved teacher at a local prep school, but also as the fiancé of the daughter of a U.S. Supreme Court justice.

As the affable and genteel "Charles Rankin" comes closer to being found out as Franz Kindler, in part due to his fixation with timepieces, the autumn shadows of the sleepy burg are stretched beyond mere seasonality into emulations of German-style expressionism. Perry Ferguson, the production designer for "Citizen Kane," created a complete town square set for "The Stranger" to enhance its naturalism for deep-focus shots, but by the film's final act, its action is dominated by the stark church clock tower and its sparsely lit inner workings.

6. The Lady from Shanghai

In spite of some glaring missteps, including Welles' cringe-worthy attempt at an Irish accent and Rita Hayworth ditching her ravishing red tresses for a bleached blonde bob, "The Lady from Shanghai" has only grown in critical esteem over time, and deservedly so. Not only was its ambience bolstered by being one of the first major films out of Hollywood to be shot almost entirely on location — in Acapulco, Pie de la Cuesta, Sausalito, and San Francisco — but the disintegration in real time of Welles and Hayworth's already estranged marriage lent an unintended frisson to the ill-advised affair between their star-crossed characters.

The succession of reveals and switchbacks in "The Lady from Shanghai" is well-timed and subtly seeded enough to qualify the film as a smart noir mystery, and its final-act funhouse visuals imbue the already dramatically heightened circumstances with a dreamlike surrealism, but its best and most class-conscious moments came from Welles' hired-hand wanderer taking stock of the casual cruelties that the rich inflict upon those whose rely on their favors to survive.

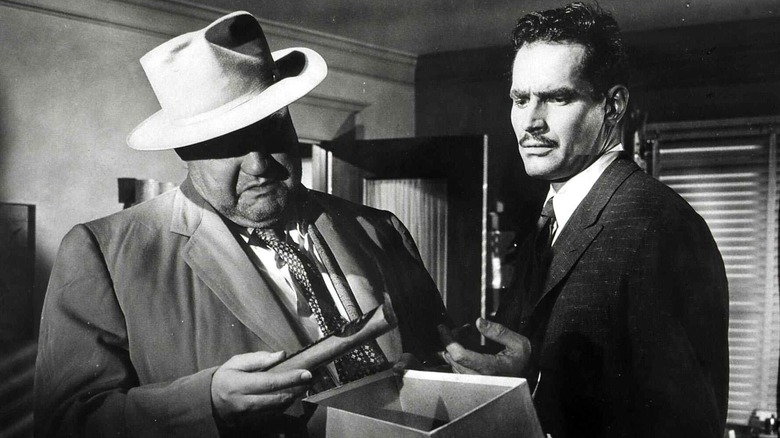

5. Touch of Evil

Welles' aggressively anti-charismatic performance as Hank Quinlan in "Touch of Evil" made no effort to conceal the dissolute police captain's unrepentant corruption, but in spite of the veteran lawman's racism and willingness to abuse his power, it becomes clear that his well-earned road to Hell was paved, at least initially, with some decent intentions.

Going sober for a dozen years has made Hank unrecognizable to his former lover, since he pulled the dry-drunk move of substituting one vice for another, stuffing his now-fat face with candy bars. Even when he dies by collapsing backward into filth, he's memorialized as "a great detective" and "a lousy cop" whose final suspect turned out to be guilty of the crime for which Hank had framed him.

As much as our national pop culture nostalgia has retroactively cast the '50s as the idyllic sock-hop era when Marty McFly's parents fell in love, 1956's "The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit" wasn't the only film from that decade to ask discomfiting questions, such as how much collateral damage we were willing to overlook in the ostensible pursuit of justice.

4. The Magnificent Ambersons

Welles harbored the wistful nostalgia of an old man even in his youth, so while his film adaptation of Booth Tarkington's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1918 novel functioned as a judgment upon the entitled culture of 19th century America's equivalent of the "landed gentry," so too did it serve as an elegy for what the film presents as the elegant simplicity of the pre-automobile era.

Tim Holt plays George Amberson Minafer as a self-centered, reactionary terror of a man-child, whose mulish refusal to concede the march of progress marks many of his follies and presages his downfall. But even Eugene Morgan (welcome back to the list, Joseph Cotten), the automobile manufacturer who courts George's mother, acknowledges that not all the changes wrought by motor vehicles are likely to be positive.

In retrospect, the studio-edited curtailments of Welles' intended narrative appear as crude as an "Itchy and Scratchy" title card reading "George Amberson Minafer died on the way back to his home planet," but there's a quiet grace in how George's long-awaited comeuppance only occurs when no one is left to see it — even the audience is deprived of the sight of his face as it happens.

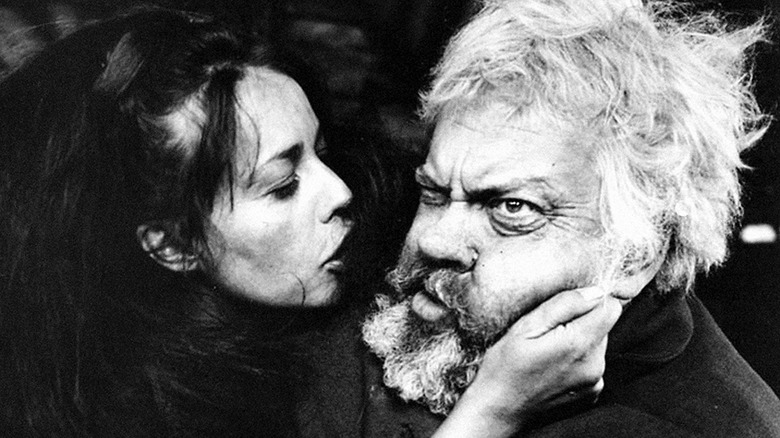

3. Chimes at Midnight

What's so wonderful about "Chimes at Midnight," beyond the excuse it affords us to spend more time hanging out with Welles as Sir John Falstaff, whom Orson himself deemed "a knightly dropout" and "a beautiful bum," is that it extends to audiences the conspiratorial sense of having snuck into a Shakespeare performance behind the scenes (or at least between them).

Like Tom Stoppard's "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead," which was first staged in 1966, "Chimes at Midnight" plays out like a collection of interludes between the central scenes in Shakespeare's plays, a style of presentation well-suited to chronicling the idle misadventures of the carefree Crown Prince Hal and his merrymaking enablers. Indeed, Welles described "Chimes at Midnight" as a lament "for the death of Merrie England," represented in the expansive figure of Jack Falstaff, "misleader of youth" and human teddy bear.

As heartbroken as Falstaff is to be renounced by his surrogate son, his already broad chest swells with pride to see the newly crowned King Henry V finally maturing and growing beyond the silly, limited old man who once looked after him.

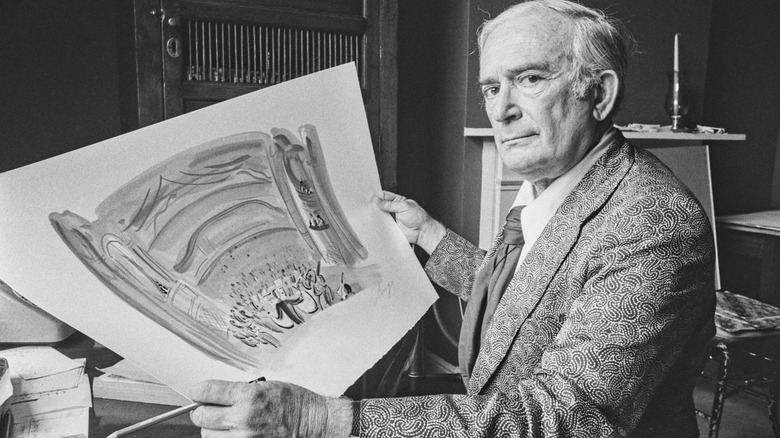

2. F for Fake

When Orson Welles presents a documentary about frauds and con artists, pay attention to his precise words, lest you discover that you've been duped.

What begins as a biography of Hungarian professional art forger Elmyr de Hory digresses into an examination of de Hory's biographer, Clifford Irving, who himself got caught hoaxing an autobiography of Howard Hughes. Along the way, Welles recalls how he got an acting job in Ireland by falsely claiming to be already famous in New York, and how he made misleading use of simulated news reports to make his 1938 "The War of the Worlds" radio drama seem more real, before he wraps up with an anecdote involving his protégé, Oja Kodar, and the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso.

It's up to you to keep track of which parts are true, but when Welles' interviews yield priceless lines like de Hory saying, "To be Hungarian, it is not a nationality, it is a profession," you'll find yourself glad just to bask in the milieu of their discourse.

1. Citizen Kane

Yes, it's the obvious choice. No, I don't care.

Because "Citizen Kane" transcended its origins as a William Randolph Hearst hit-piece even before its script was finished. If "The Magnificent Ambersons" captures the death of the 19th century, "Citizen Kane" regales us with the ramp-up to the birth of the 20th.

Kane isn't just Hearst; he's every innovator of mass-media in our lifetimes, including Rupert Murdoch and Mark Zuckerberg. For the first act of his story, we're rooting for his schoolboy antics, even when he threatens to start the Spanish-American War on a whim, because he and his buddies are having so much fun. Which makes it all the more bittersweet when Kane betrays his wife, his best friend, and his stated principles, all to try and satisfy his ever-escalating need for more (of what, even he can't say).

"Citizen Kane" abandons linear chronology to show us how love can gradually leach out of a marriage, and how a self-appointed champion of the people can calcify into everything he hates. "Citizen Kane," in short, is the story of America.