The True Story Behind The Great Escape

For many of us Brits, just the mere mention of "The Great Escape" provokes an urge to tuck into a large plate of turkey sandwiches. When I was growing up, John Sturges' rousing prisoner-of-war thriller seemed like it was on telly every Boxing Day, and it is still regarded as a festive favorite in many U.K. households. At three hours long, it was perfect holiday viewing, ideal for killing off an afternoon drifting in that post-Christmas funk, with the grown-ups grazing steadily in front of the TV while the kids played with their new toys.

In his list of 10 great prisoner-of-war films for the BFI, critic Samuel Wrigley described it as the "epitome of war-is-fun" action films. From an era well before films like "Saving Private Ryan" showed us that war was hell in harrowing detail, "The Great Escape" is an upbeat war adventure for the whole family, playing up the ingenuity and resilience of the Allies, reassuring us that we were the good guys, and avoiding too much of the darker stuff. Sure, a lovable character is shot dead trying to claw his way over a fence and 50 prisoners are summarily executed at the end, but how could you possibly feel bad watching a movie with music as chipper as that Elmer Bernstein score?

While other POW movies like "The Colditz Story" and "Stalag 17" have largely fallen by the wayside, "The Great Escape" remains enduringly popular, perhaps thanks to its terrific international cast including Hollywood stars Steve McQueen, James Garner, Charles Bronson, and James Coburn, all running circles around the Germans. The film stays true to many of the key details of the escape itself, but the screenwriters took several liberties in the narrative, including the nationalities of the main protagonists. Let's take a look.

So what happens in The Great Escape again?

It is 1942 and the Nazis decide to "put all their rotten eggs in one basket;" round up the most troublesome Allied escape artists and put them all in their shiny new "escape-proof" camp, Stalag Luft III, under the supervision of gentlemanly Colonel von Luger (Hannes Messemer). What could possibly go wrong?

The latest arrivals at the camp waste no time casing out the place and making a few impromptu escape attempts. A few including Danny Welinski (Charles Bronson) try walking right out the front gate disguised as workers, while Virgil Hilts (Steve McQueen) checks the fence for blindspots and lands himself a stint in solitary confinement along with Scottish flyer Archibald Ives (Angus Lennie), who will become Hilts' partner-in-crime for future escape attempts.

Roger Bartlett (Richard Attenborough), designated "Big X," arrives in the custody of the Gestapo. He's in charge of a committee devoted to hatching escape plans and he immediately gets cracking on his masterpiece, despite dire warnings about the consequences should he get caught again. He aims to undertake the biggest breakout ever, planning the construction of three tunnels to bust out 250 men from the camp.

Working with his second-in-command Andy MacDonald (Gordon Jackson), a.k.a. "Intelligence," they assign prisoners various tasks according to their abilities. Welinski is the "Tunnel King," despite his closet claustrophobia; Bob Hendley (James Garner) is the "Scrounger," using his laidback charms to acquire contraband; his mild-mannered British roomie Colin Blythe (Donald Pleasance) is the "Forger," in charge of creating counterfeit documents, and so on.

The central part of the movie is devoted to digging the tunnels, snaffling building materials, and creating vital civilian clothing and important documents for when they get out. Once the work is complete, however, getting out of the camp is only half the battle.

The origins of The Great Escape

"The Great Escape" is based on the book by Paul Brickhill, an Australian fighter pilot who was a prisoner at the real Stalag Luft III in modern-day Poland. He had a minor role in the escape plan acting as a "stooge," tasked with keeping tabs on the German guards, but wasn't allowed to join the breakout itself due to his claustrophobia.

The main details of the escape were kept fairly faithful in the film. The camp was designed to be escape-proof, with the prisoners' living quarters built on sand and raised off the ground to deter tunneling. Naturally, that didn't deter the escape committee and around 600 of the 1800 inmates were involved in the planning and construction of the three tunnels, stripping timber from the huts to shore up the earth and finding ingenious ways to dispose of around 100 tons of sand (via History.com). One aspect that both the book and the film play down is that a large proportion of the prisoners had absolutely no intention of attempting an escape.

While the plan was to take out over 200 men through one completed tunnel, only 76 made it out on a snowy March night and faced the challenge of escaping German territory. Brickhill claimed that around 5 million Germans were involved in trying to round up the escaped prisoners.

Seventy-three men were recaptured and 50 were shot, violating the Geneva Convention which forbade killing POWs for trying to escape. Unlike the film, the summary executions were done either singly or in pairs (via Sky History). After the war, the British Royal Air Force conducted a three-year manhunt to catch the killers and bring them to justice. Only three managed to get away, two Norwegians and a Dutchman, rather than a Pole, a Brit, and an Australian.

The real Big X

While some of the characters in "The Great Escape" are composites, others directly correspond with their real-life counterparts. One of the main protagonists was "Big X," British Squadron Leader Roger Bushell. Shot down in 1940 while providing air cover for the Dunkirk evacuation, he made his first escape attempt from Stalag Luft I. He successfully got out of the camp but was caught again trying to cross the border into neutral Switzerland.

During his transfer to another camp, he jumped off a train with a Czech pilot. Together they made their way to Prague, which was under the brutal control of SS Reich-Protector Reinhard Heydrich. They hid with a Czech family for eight months before an informer gave them up. Bushell was interrogated by the Gestapo for his suspected involvement in the plot to assassinate Heydrich in Operation Anthropoid.

His experiences in Prague and first-hand knowledge of the Gestapo's methods gave Bushell a special hatred of the Nazis, making him even more determined when he was put in charge of the escape committee at Stalag Luft III. He planned to cause as much disruption to the Germans as possible with the unprecedented scale of the breakout.

In "The Great Escape," Bartlett's capture is one of the most memorable. Earlier in the film, he and MacDonald test the prisoners' command of German before catching them out with a few words of English. Just as they are about to make their getaway, a Gestapo officer catches them with exactly the same trick. There is some debate about whether this actually happened or not. Bushell was traveling with a French officer and, although Bushell spoke fluent French and German, historians believe that if a linguistic slip-up really occurred, it was more likely to come from Bushell since his native language was English.

The Cooler King and the Tunnel King

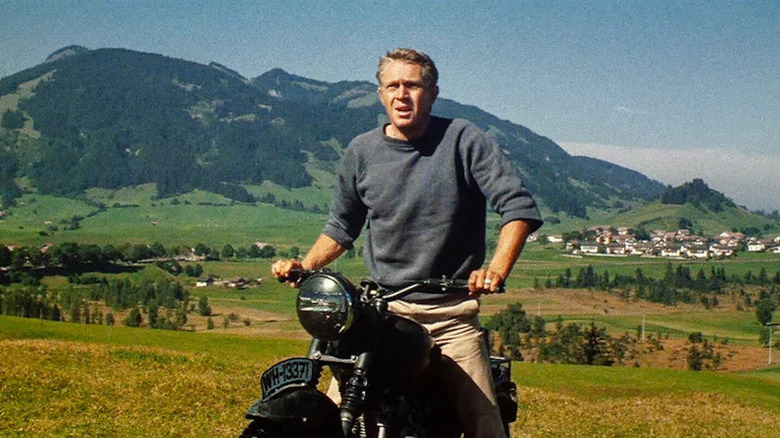

"The Great Escape" was a star vehicle for Steve McQueen, and he contributed the film's most thrilling sequence when Hilts steals a motorbike and tries to jump a series of barbwire fences into Switzerland. The daring stunt never happened in real life and was only added at McQueen's request, who was an avid motorhead.

McQueen performed most of the motorcycle riding himself apart from the final jump, which was the work of stuntman Bud Adkins (via Motorcycle.com). However, McQueen and motocross champ Tim Gibbes both apparently pulled off the jump on camera for fun, and, according to the Second Unit Director, the shot used in the film could have been either of the three men.

Hilts is inspired by William Ash, a charismatic American fighter pilot who repeatedly tried to escape captivity with a number of daring attempts. As a result, he spent a substantial amount of time in the cooler before eventually escaping a few days before the war ended (via BBC). Ives, Hilts' tragic escape partner, was based on Jimmy Kiddell, who was shot dead trying to scale a fence.

Just like his character, Charles Bronson suffered claustrophobia from working down the mines in his hometown as a teenager. The Tunnel King was based on Canadian flyer Wally Floody, whom Bushell put in charge of constructing the three tunnels. While Danny overcomes his fear to become one of the three successful escapees, Floody never even made it through his own tunnel. He and a group of other men were sent to another camp before the escape took place after German guards noticed some suspicious activity. After the war, he received an MBE for his commitment to the dangerous task of digging the tunnels and served as a technical advisor on "The Great Escape."

The Forger

One of the saddest storylines in "The Great Escape" is the demise of Blythe the Forger, played beautifully by Donald Pleasance. The tea-loving Brit is roommates with the American charmer Hendley, and the pair form an unlikely friendship. When it becomes apparent that Blythe's eyesight is deteriorating at a rapid rate, Bartlett decides he can't go out through the tunnel because a near-blind man could prove a danger to himself or others. Hendley says he will take responsibility for getting Blythe out and Bartlett relents. In a tragic twist, Hendley unwittingly sends his friend in the direction of German soldiers after their stolen plane runs out of gas and crashes. Unable to see the danger, Blythe is shot and dies in Hendley's arms.

The sudden worsening of his eyesight initially appears to come as some surprise to Blythe when his vision blurs, but he later states he has "progressive myopia," suggesting he was diagnosed at some point previously. In the real camp, there were no cases of POWs losing their eyesight, although some forgers suffered severe eye strain from working on documents in minute detail. Some had to quit the task because of it.

Blythe is tasked with overseeing the production of all official documents that the escapees will need to safely navigate spot-checks while traveling across German-occupied territory. The film suggests all this was done from scratch, although in reality, the team of forgers received plenty of assistance acquiring paperwork from anti-Nazi Germans, including some of the guards.

Like Hilts' motorcycle jump, Hendley and Blythe stealing a plane to leave the country was also fiction; no prisoners stole vehicles to aid their escape.

The Commandant

Oberst von Luger is presented as an honorable senior Luftwaffe officer with anti-Nazi views, and he corresponds closely with the real-life commandant of Stalag Luft III, Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau.

Von Lindeiner-Wildau was a decorated German officer who began his military career at the turn of the 20th century and served during World War I when he was awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class. Well-educated and speaking good English, he was a successful international entrepreneur in the interwar years before moving back to Germany in 1932. He was loyal to his country but despised the Nazis, refusing to join the Party. Nevertheless, he was offered a position in the Luftwaffe as one of Hermann Göring's personal staff.

During the Second World War, he accepted the position of Commandant at Stalag Luft III, seeing it as a chance to serve his country while distancing himself from the worst aspects of the regime he hated so much. He was well-respected by the POWs and tipped them off about the dangers they faced if caught escaping (via The National Archives).

Like von Luger in the film, von Lindeiner-Wildau was also relieved of his duties after the escape and questioned by the Gestapo during a spell of "fortress confinement." At the end of the war, he was injured by advancing Russian soldiers and surrendered to the British, becoming a POW himself before testifying in the investigation into the murders of the 50 escapees. He later donated material for a memorial to the victims, which is situated near the site of the camp.

His replacement at Stalag Luft III, Oberst Franz Braune, was also appalled by the murders and allowed the remaining prisoners to build their own memorial, which is still standing today (via War History Online).

The Hollywoodization of The Great Escape

One of the most frequent criticisms regarding the accuracy of "The Great Escape" is how much the screenwriters overstate the involvement of American officers. While some were initially involved as lookouts, they were shipped out to another camp several months before the escape took place (via Sky History). One exception was American-born British Army officer Johnnie Dodge, who had previously escaped Stalag Luft I with Roger Bushell. Conversely, the film totally fails to mention the 150 Canadian officers who, like real-life Tunnel King Wally Floody, were instrumental in the escape.

Overall, I don't think the changes made to "The Great Escape" detract much from the bravery and resourcefulness of the real men who pulled off such a remarkable feat. After all, it is a film that we Brits have taken to our hearts despite its "Hollywoodization," and Elmer Bernstein's famous theme tune has even become a sort of alternative English national anthem, frequently heard at international football matches.

"The Great Escape" still holds up extremely well almost 60 years later; I can't think of very many other three-hour movies that zip past so quickly, even after repeat viewings. I've probably seen it about 20 times since I was a kid. My granddad served in the RAF and he was quietly proud of his small part in defeating the Nazis, and it was one of his favorite films. As a result, we'd always end up watching it if it was on TV at Christmas.

Now, like his war stories, "The Great Escape" feels like a family heirloom to pass down. I've made a start, watching it with my seven-year-old daughter recently. She was totally engaged throughout, which maybe wouldn't be the case if it was more realistic and less purely entertaining. Sometimes accuracy isn't the most important thing.