A 'Communication Breakdown' Cost Steven Spielberg A Poltergeist Screenplay From Stephen King

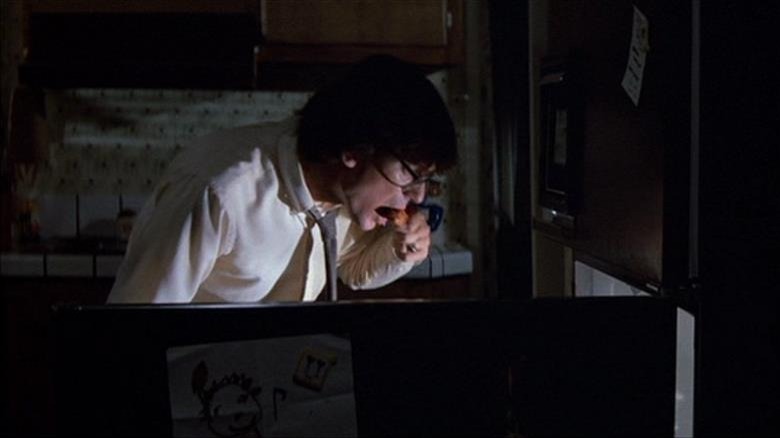

"Poltergeist" is a cinematic Rorschach test. Which scene was scarier, the maggoty meat or the evil clown doll? What does the film say about the values of 1980s American suburbia? Most importantly of all, did Tobe Hooper direct the film, or did producer Steven Spielberg do it on the sly? Director Mick Garris insists it was Hooper, but "Poltergeist" camera assistant John R. Leonetti says Spielberg. Film critic Scout Tafoya claims in "Cinemaphagy," his book covering Hooper's film career, that "Poltergeist" is Hooper's movie but has some distinctly Speilbergian touches.

There is another "Poltergeist" that never quite came into being. Early in the film's production, Spielberg decided that he needed help writing the script. In search of a horror expert, he turned to Stephen King, whose works at the time were tearing up the country's bestseller charts. King was away at the time, and by the time he returned, Spielberg had moved on. Despite many close calls, Spielberg and King have never once collaborated in the years since.

Two ships in the night

Spielberg and King both came to prominence in the 1970s. According to Entertainment Weekly, King's novel "Carrie" was published on April 5th 1974, the same day that Spielberg's first theatrical feature, "The Sugarland Express," was released. Spielberg made his name as a horror director with the following release of his proto-blockbuster "Jaws" in 1975. Two years later, King's haunted house family drama "The Shining" proved a long horror novel could be successful and marketable.

Of course, the two artists had successes and failures. Spielberg's "1941" bombed with critics, while King's 1977 active shooter novel "Rage" (published under his Richard Bachman pseudonym) was bad enough he asked for it to be removed from publication. But by the early 1980s, Spielberg and King were on the verge of becoming not just popular artists of the decade, but popular artists of their respective lifetimes.

"Poltergeist" would have been a perfect opportunity for these two to work alongside Tobe Hooper, who had directed a well-regarded "'Salem's Lot" TV miniseries in 1979. But it was not to be. In the aforementioned Entertainment Weekly article, King would say that "it didn't work out because it was before the internet and we had a communication breakdown." A Vanity Fair feature says King was on "a ship going across the Atlantic" when the offer was made.

Whether or not King ever seriously considered the opportunity, Spielberg reached a point where he no longer had time to entertain a King collaboration. He chose to move on rather than put the production schedule at risk. Spielberg and King would toy with collaboration later in their careers, most notably in the seed of what became King's 2002 TV miniseries "Rose Red." But these talks have only ever been talks.

A precarious balance

At first glance, Spielberg and King are eminently compatible artists. The two of them steal flagrantly from the entertainment of their youth, with Spielberg lifting scenes from "Donald Duck" branded comics by Carl Barks as easily as King takes inspiration from the gruesome tales published by EC Comics. Not to mention, as the podcast Just King Things repeatedly points out, King's career owes as much to pulp science fiction tales as it does to the horror he is more traditionally associated with.

In recent years, as the 1980s have come back into fashion in American pop culture, filmmakers have freely mixed characteristics of Spielberg and King. "Stranger Things" owes as much to Spielberg's suburban nostalgia as it does to King's mythos of a rotting United States. Even the recent film adaptation of King's "It" unmistakably bears Spielberg's influence.

At the same time, there is reason to believe that a film collaboration between Spielberg and King would be a disaster. King is a talented novelist, but his screenwriting career consists of forgotten cult objects ("Storm of the Century,") fiascos ("Maximum Overdrive") and straight-up duds (his miniseries adaptation of "The Shining.") Talented filmmakers have worked wonders with his short stories, like how "The Body" was adapted into the classic "Stand By Me." But King has a natural tendency to sprawl, which rarely suits movie length. As Scout Tafoya says in a Polygon piece, "King's books create and destroy communities, or even entire worlds, in order to show how precariously so much of American civilization is balanced." This sense of scope is workable within the length of a miniseries like "'Salem's Lot," or a film duology like "It." But King suffocates within the constraints of a two-hour film.

Our lot in life

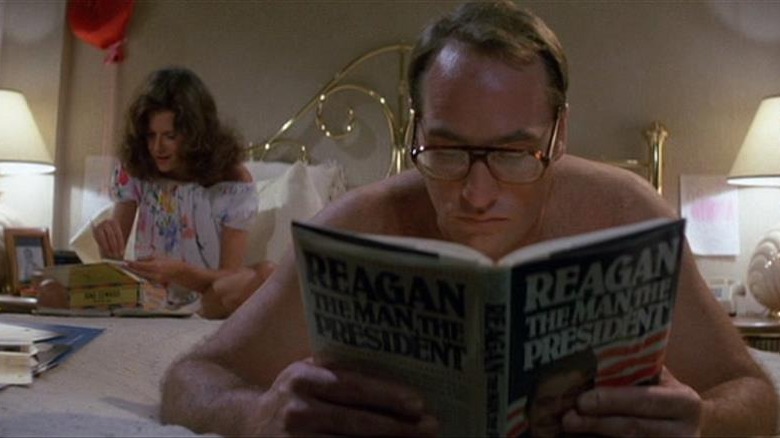

Despite their surface-level similarities, Spielberg and King are quite different. Certainly, Spielberg has done horror and King's books have moments of uplift. But Spielberg's movies are famously sentimental, sometimes to their detriment. The tremendously accomplished suspense sequences in Spielberg's "War of the Worlds" are neutered by an ending that goes out of its way to reassure the audience that everything will be alright. By comparison, King at his best is a bleaker writer than Spielberg is a director. Certainly he chooses to believe in God, as well as in the idea that "evil will undo itself." But these beliefs are repeatedly challenged by forces of fear, addiction and compulsion that he has struggled with for his entire adult life. King's best novels, like "The Dead Zone" and "Cujo," are (as Tafoya says) portraits of American dysfunction in which survival, or the comfort of the dead, is as happy an ending as you are going to find.

Rather than being disappointed that we haven't gotten a Spielberg and King film collaboration, the real tragedy is that King never made a movie together with Tobe Hooper. Certainly we have "The Mangler," Hooper's adaptation of a King short story that was widely derided on release (but has attracted fierce defenders over the years.) But Hooper's anarchic sensibilities would have made him a prime candidate to untangle the nastier side of King's imagination, which has long been buried by stultifying cultural nostalgia. Who else better to tackle King's lifelong obsession with the Kennedy assassination than the director of "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre?" Sadly, Hooper has passed. But "Poltergeist" remains, and it's as much a tribute to Hooper's skills as a filmmaker as to Spielberg's populist instincts.