Sergio Leone Saw Filmmaking As Something Akin To A Religion

Few storytellers have shaped the modern American Western than, ironically, Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone, who approached the genre with an outsider's view and pioneered the Spaghetti Western. Unlike his predecessor John Ford, Leone portrayed his "heroes" as morally ambiguous and argued that survival and greed shaped the American frontier more than duty and honor. Though he may have seemed cynical, Leone revered the filmmaking process, lending his passion and worth ethic to future filmmakers just as much as his visual style.

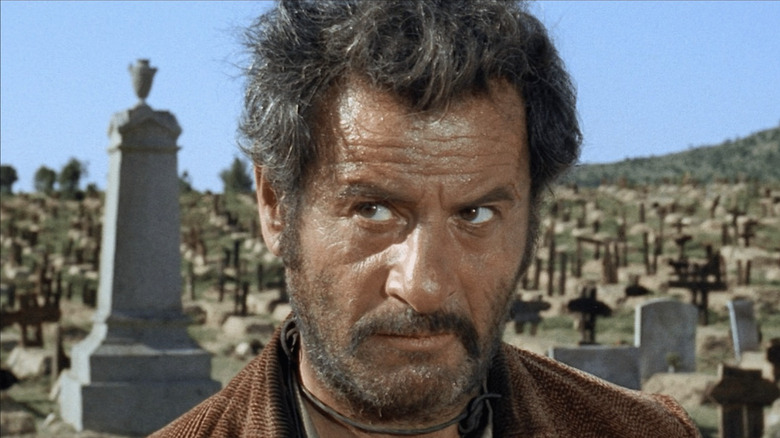

Sweeping vistas interspersed with dramatic close-ups were Leone's trademarks, a juxtaposition between the powerful landscapes of the open frontier (shot mostly in Spain rather than the United States) and the dirty, sweaty faces of its worn-out and corrupt settlers. As influential as these camera techniques were, Leone had a special affinity for what happened in post-production, treating editing and sound mixing like they were sacred rites.

The Editing Room Altar

Leone's father Vincenzo, who went by Roberto Roberti professionally, was also a filmmaker who exposed his son to the behind-the-scenes process, As a result, Leone was already familiar with how a large, intermingling crew of technicians and artists working with a vast array of technology was how movie magic happened. As a cinephile from a young age, Leone was plainly aware of the technical grit of filmmaking yet nevertheless transfixed by the final product. This fascination with the dual sides of the medium was why Leone treated his own projects with the utmost respect, knowing that careful post-production work ethic could turn the Spanish Tabernas Desert into the American Old West. In his own words, Leone expressed in a 1984 issue of "American Film" magazine:

"I knew that... on the other side of the cinematic field, beyond the geometric lines of the screen, great masses of technicians, makeup artists, scene shifters, and hairdressers crowded in. I knew all about electric cables, cameras, microphones, reflectors. It's probably also because of this that the technical side of my moviemaking is so important. I go to the dubbing room as if I'm going to Mass, and mixage, for me, is the most sacred rite... the Moviola [an editing machine] is the altar of a voodoo rite. One sits down in front of the console and plays his hand with the heights of the heavens. I always knew that films were made by men and structured like prayers."

Rituals of the American Myth

Leone also explained the profound impact that American culture had on him while growing up in Italy both during and after the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini. Exposed to the United States through the films and novels that were translated into Italian after the war, the filmmaker claimed that he "must have seen three hundred films a month for two or three years straight." Throughout this discovery, he realized that the idea of the American myth was prevalent worldwide, in both native and European conceptions of the nation:

"America was something dreamed by philosophers, vagabonds, and the wretched of the earth way before it was discovered by Spanish ships and populated by colonics from all over the world. The Americans have only rented it temporarily. If they don't behave well, if the mythical level is lowered, if their movies don't work any more and history takes on an ordinary, day-to-day quality, then we can always evict them. Or discover another America. The contract can always be withheld."

In other words, Leone was perfectly suited to make Westerns (and, later, a gangster film) because the mythological idea of America isn't necessarily exclusive to Americans themselves. His Spaghetti Westerns, the Westerns of John Ford, and by the same token, American crime films, are all part of the same mosaic of modern mythology, more concerned with creating legends about American identity and culture than retelling history. If that's the case, then Leone has to treat them with reverence. After all, myths are sacred.