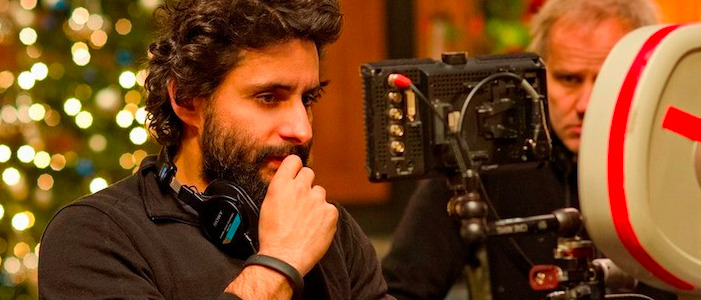

Interview: 'The Shallows' Director Jaume Collet-Serra On "The Fear That Lasts A Year"

With The Shallows, director Jaume Collet-Serra may have taken on his biggest challenge yet as a filmmaker. The director of Orphan, Non-Stop, and Run All Night made a film primarily set on the water, featuring an entirely CG antagonist, a great white shark, and a co-star that's a seagull, whom Blake Lively's character names Steven Seagull. All these factors added up to a production that, Collet-Serra admits, wasn't easy.

Collet-Serra typically relies more on practical effects, so The Shallows was a more CG-heavy experience than he was probably used to. The director was kind enough to take the time to discuss the experience of making The Shallows with us, and why the CG shark proved to be "the fear that lasts a year."

Below, read our Jaume Collet-Serra interview.

Did you see how positive the reaction was to the last trailer?

I know. I saw that trailer many, many months ago. I was excited, too. The marketing people worked very hard to have an unusual campaign, and hopefully, you know, it can differentiate this movie from whatever else is in the marketplace today.

How much input did you have in the marketing?

Yeah, you have to, because [then] the movie doesn't exist. This movie happened so fast. We were in the editing process with no shark, being built in CG, so there were a lot of questions about what we could accomplish in time to release something in the trailer. It's not like some movies where they're almost finished by the time they start the marketing. Here, they had to start the marketing before the movie was even close to finished. We had a lot of discussions and ideas. That's a trailer that we liked from the very beginning, thought it was very special. We're glad they released it.

What's that feeling like on set, knowing you're not going to see the main antagonist of the film until later on in post-production?

It's a fear that lasts a year. You don't see the shark. It's not like we do a movie and jump into the movie knowing we can do it; we hope we can figure it out. You just jump into the water and get wet. The first time I edited the movie, the shark was a dot. You just put a dot on the screen that's red, and it moves across the screen, from left to right to right to left. Then you move to the next stage, where you have a very rudimentary, not even like a flat animation of a shark, but a cutout, you know? Then you keep moving forward until you eventually see the real shark, but you never really see it. I just saw it for the first time two weeks ago. But it comes into pieces, to be honest.

Every once in a while, you get a really good shot, like the one in the trailer where the shark is coming out of the water and eats the surfer. You see that early, like two months ago, and say, "Wow. Great. I have another 100 shots to go." You start seeing the other shots — and some work great at the beginning, some just don't work and you adjust.

It's work. Every day, for hours and hours, with a laser pointer and a conference call, talking to different teams all across the world, telling them: "What about this? What about the muscles under the mouth? Can we do something here in the eye?" It's every detail, every frame, and every gesture.

There's a lot of control. The problem is, there are 1,100 shots in the movie, right? If I spend, maybe, one minute looking at each shot and get to review it three times, if you add that up, that would be two weeks of full-time work for me. Those are eight-hour days looking at shots. What that tells you is that I can maybe see a shot three times before it's done. The first time, if it doesn't look very good, you try to make it look good. By the third time, you're adding details, but you can't do big changes. That's why big movies often get pushed around in the schedule and whatnot, to give more control and time to the director, because these things take a lot of time. Because we wanted this to be a summer movie we knew we had to make strong decisions and make them early in the process to make our date.

Filmmakers often say don't shoot on the water.

Filmmakers often say don't shoot on the water.

They're right.

What did you find most challenging or surprising about the process?

Well, what was surprising was how good the crews working in water are. I could never do that. Like, the guys who actually operate the cameras underwater, the people there for safety, and everyone working on the water are really strong people. We had a team of safety divers and crew that were just amazing. Now, everything takes very long because water destroys everything, you know. If it gets into the waterproof cage, it fogs everything, destroys the cameras and lenses. You have to be extra careful, dry everything, and pressurize everything. Every time you're around water, the weather, the wind, and the tide changes. Nothing is consistent. You think you're ready, and then suddenly the wind changes and your boat is going the opposite way, and now the crane is looking the other way. There's nothing you can do about it. Even if you anchor the boats four times or whatever, if the ocean wants to move you, you're going to move. So, it's very, very tough. I don't recommend it; I recommend shooting in a restaurant.

There are a few specific sequences and shots I want to touch on, and I'm just curious what you remember most about crafting these scenes.

Sure.

At the start of the film, cutting from Nancy surfing, with that song playing, to underwater, with no music and the sound of the waves crashing, is effective.

We knew that the camera always had to be on the surface, on the edge, having it above and below. That creates a lot of problems because a camera can work very well outside of the water, and you have a splash cam, which is not going to go under the water but is going to be waterproof. If you go underwater, it's going to be very stable under the water, but just to have it on the surface and be able to go up and down is very difficult. I was very clear from the very beginning I wanted, at that moment, to be in that space, to create the tension of what's lurking underneath. The whole movie is like that. That's very difficult, technically. It was the whole approach from the very beginning: at any moment, something can pop up right up in front of you. Because if you go really out of the water, then there's a sense of security.

How about the shot of Nancy when she's attacked and all you see is her and blood under the water?

That comes from what I've heard from victims of shark attacks, that the first thing that happens is that the whole water goes red. That's what they remember: the water going red. I didn't want to see the shark actually attack her because she wouldn't be seeing it. People don't see it, they feel a little tug and then feel being pulled. I just wanted to show her, and then it wouldn't become something that was too gruesome and too shocking. That's why I stayed with her.

Another example of that, which is also a clever way of avoiding an R-rating, is one long reaction shot. I won't spoil it, but the look on Nancy's face tells you how horrific what's happening is.

Everybody thinks that I make my decisions of my PG-13 rating. I didn't even know what rating I was doing; I'm just designing the movie for what I think is the scariest and the most effective. Now, that shot, when we push into her face, isn't necessarily planned. Well, it is planned, but she delivered that performance, and she makes me not want to cut away from her; she earns that closeup. If she was terrible in that closeup, I would cut something to else, but she's wonderful, and so I wanted to stay there. The way that we shot the movie was she did the scene every time, from beginning to end, [spoiler alert] from waking up to seeing the guy die almost in one shot [spoilers over]. We were going in and out with the crane, trying to get angles, and it's just a dance we do with her and the cameraman so that we can get something impactful. When something works, it clicks, you know you have it, and that it has to stay in the movie as a full shot.

***

The Shallows opens in theaters June 24th.