Screenwriter Max Landis Wrote A 150-Page Ode To Carly Rae Jepsen – And It's Brilliant Storytelling

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Max Landis is a writer's writer. While his subject matter is thoroughly accessible, he isn't the type of guy you hire for your standard studio fare. The screenwriter behind films like Chronicle, American Ultra, and Bright is obsessed with structure, with word play, with the subversion of tropes and clichés. He's exactly the type of writer that other writers study, marvel at – scratching their heads at how deftly he manages to turn genre on its ear or how he crafts entire acts of films that play radically different upon second viewings. And he's also a writer's writer in the Hemingway sense, insomuch as you're probably as accustomed to hearing his name in reference to his afterhours shenanigans as you are hearing about his work. As a critic, I've tried to avoid writing sentences like that last one as, more often than not, a subject's personal life has little bearing on their work – but bear with me, because in Landis's case, who he is publicly is as important to his work, and A Scar No One Else Can See, his 150-page "living document" on the work of pop star Carly Rae Jepsen, as anything else.

Landis has been candid about his own personal demons, and even more candid about his use of drugs and alcohol to self-medicate. And those demons are on display in almost every single piece of produced fiction he's written. If there's one prevailing theme that links nearly all of his work together, it is that of truly broken individuals finding respite, and ultimately deliverance, in the arms of another person. Evocative of Paul Thomas Anderson's Punch-Drunk Love, Landis's work is often about people who want to be loved, are far too damaged to find love orthodoxly, and then find it in the most unexpected, unconventional ways. And it is through that love that the protagonist can begin to become whole. Whether the character is a warped MK Ultra experiment, an undiagnosed sociopath, a pathological liar lying about an illness for money and sympathy, or a broken-hearted lesbian who dabbles in bi-sexuality after a break-up, the theme remains – it is always when the characters find someone who accepts them for who they are, unconditionally, warts and all, that they can find some sense of normalcy and begin to be healed. It is as if Landis is constantly arguing with Jean-Paul Sartre, whose thesis of No Exit is that "Hell is other people," with Max yelling from across the table "No JP, Hell is the absence of other people! Other people are our salvation, not our punishment!"

Yes. You just read a Sartre reference in a piece on Max Landis's take on Carly Rae Jepsen. If that threw you for a loop, strap the fuck in buttercup, because you're in for a bumpy fucking ride.

The Films of Max Landis

Another recurring element of Landis's work is his use of misdirects and double meanings. You see, Landis is obsessed with language and structure – particularly with writing scenes that play one way before a twist, and then as something else entirely once the narrative has changed. In American Ultra, we open with a fairly mundane series of scenes: a pothead convenience store clerk wants to take his girlfriend to Hawaii in hopes of proposing, while getting over his mental issues that prevent him from leaving his small town. But when he can't bring himself to get on the plane, the long ride home brings a conversation with his girlfriend and her disappointment in him. The first time through, it is a fairly innocuous scene in which she tries to express that she isn't mad with him, even though she clearly seems to be. But once the rug is pulled out from under us and we discover that this convenience store clerk is actually a mentally damaged MK Ultra experiment and his girlfriend was his CIA handler, that scene becomes a decidedly different story. She really isn't mad at him; she's mad at herself for ever thinking he could be fixed and that she could ever lead a normal life with him. All at once she is realizing that she is committing herself to a life with someone who may not ever be a fully functioning human being and every decision she has made up until that point in her life may have been a huge mistake.

Similarly, American Ultra's sister film Mr. Right (the second film in Landis's MK Ultra trilogy – the third script of which is as yet unproduced), opens as your typical, tired, by-the-numbers rom-com starring Anna Kendrick as the-stereotypical-girl-who-just-can't-get-her-life-together-and-can't-keep-a-man struggling to find love in the modern world. Only that ain't what the movie is about at all. By the time the last reel has spun out, we've learned that Kendrick isn't the boilerplate character that Jennifer Lopez played in almost every rom-com of her career, but rather is a sociopath whose life is a mess because of her complete inability to properly connect with the people around her. While her story is about finding love with a strange new guy with a mysterious career, Sam Rockwell is another brain damaged MK Ultra experiment in a completely different movie satirizing One-Last-Job crime films with its own series of twists and turns. And eventually, those two movies intersect. Sure enough, that first act plays very differently on a second viewing, with patches of dialog meaning something radically different than you thought it did the first time around.

So here we are, almost 900 words into this piece and you're beginning to wonder: what the hell does any of this have to do with Max Landis's take on Carly Rae Jepsen?

Only everything.

Criticism as Art (and Storytelling)

The great irony of criticism is that it is an imperfect artform. In perfect criticism the writer should be invisible; the criticism, after all, is about the subject, not the writer. But that's impossible. The things you notice about a work, the choices you make of what to mention, the very way you structure the piece, informs the reader as much about who the writer is as it does the subject. To illustrate that, think of five things, and only five things, you would tell me about your best friend. Just think on that for a second. Those five things will tell me as much about you as them. Did you mention their race? Their religion? Their hair color or style? Their personality? The way they chew on their thumb when they're nervous? These choices matter. And what Max Landis has chosen to critique matters as well.

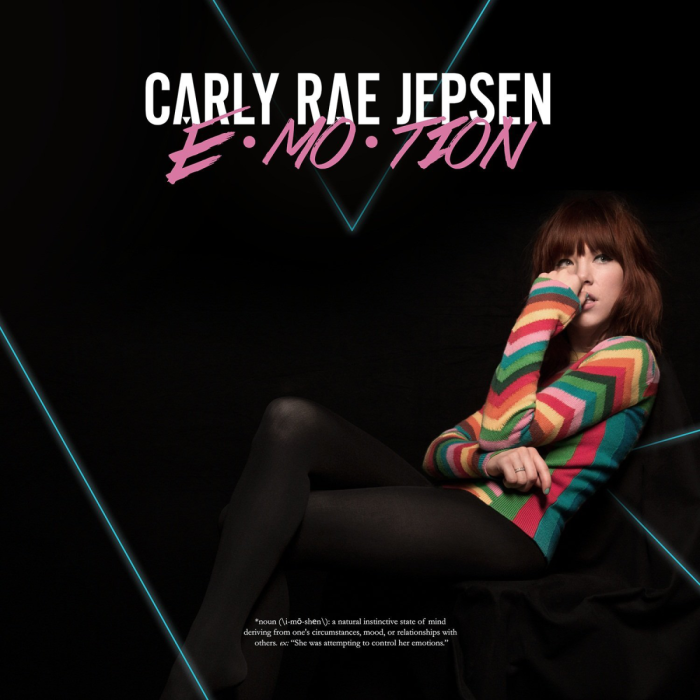

Landis has, to date, authored three major works of criticism. The Death and Return of Superman, a 17 minute short film on the biggest comic narrative event of the '90s; Wrestling Isn't Wrestling, a 24 minute short film on the 20 year narrative of Triple H's career; and now A Scar No One Else Can See, a 150 page thesis on the story behind every single song Carly Rae Jepsen has ever written. What do these three works share in common? Narrative. They are all works establishing narrative in mediums that are not wholly respected for having them.

That's Landis's obsession. As a writer, and one so focused on the technical aspects of crafting a narrative, he is drawn like a moth to a flame to stories existing in works that differ from his own craft. And while Landis tells the occasional story about himself or how he fell down some particular Carly Rae Jepsen rabbit hole, he tries to otherwise stay invisible, to keep Jepsen, her music, and what it means, front and center. And yet, there he is, naked and bare in every observation, seeing a story about a titular scar no one else sees, running through the entire discography of someone most people would consider a one-hit wonder.

Now, I've been a fan of Landis's work for some time now, and when he announced in June of this year that he was considering writing this massive tome about something as batshit crazy as Carly Rae Jepsen, I was all in. I knew that whatever this was, it was going to be interesting. So when it finally dropped, I cleared my schedule for the night, sat down with a single glass and a bottle of Buffalo Trace, and I went into it exactly as many of you might: more interested in seeing just how fucking crazy this whole endeavor was than I was in any connective tissue to be found in Carly Rae Jepsen's work. But Max is a storyteller; he not only knows how to break apart a story and put it back together, he also knows how to execute it. And that's what he does here.

Unraveling the Mystery

A Scar No One Else Can See is a masterwork of bizarre storytelling. What at first appears to be a long-winded piece of music criticism, slowly becomes a three-dimensional rendering of a character – whether real or conjured Landis isn't certain – that stays solid and unbroken over the course of three albums, two EPs, and dozens of singles. In Jepsen, Landis has found a kindred spirit, an identical soul – he's staring into a mirror at a broken writer, desperate for the love that will make her whole, a love that will tend to all her broken pieces, who is fond of lyrical third act twists that take her light, effervescent fluff and turns it, on a second listen, into "pitch black pop." Her songs are almost never what they appear to be at first glance. You have to wait for the shoe to drop in the third verse, then listen to them again. Whereas Landis writes off-kilter comedies about very dark, broken people, so too does Carly Rae Jepsen write airy, danceable tunes about a love she had, ever so briefly, then lost, and has never been able to get over. It is, as one of her lyrics states, a scar no one else can see.

Until Landis saw it.

What unravels over the course of 150 pages is a narrative mystery, one that at first you entertain for the sake of it. Landis begins the document the very same as you: skeptical, joking, giving you the old nudge-nudge-wink-wink "I'm a total nutter for even doing this," routine. And it paves the way well for what is to follow. And as he breaks down the one and only Jepsen song we all know, he begins to hand us pieces of the engine that drives it. He defines the seven themes present in any Jepsen song – some songs only having one, most of them three, with a few rare keystone songs possessing all seven. And then he starts digging up clues. These clues at first seem to be exactly what many critics mocking Landis accuse him of – common tropes and themes present in pop music. But they keep showing up. And they keep getting more and more specific. So specific in fact, that by the time you're halfway through the second album, all doubt of this being coincidence is gone from your mind.

Carly Rae Jepsen is telling a story through her music about a girl who fell in love with a boy who couldn't be hers, screwed it up, and he bailed, leaving her pining for him over the course of the better part of a decade. And as she tells that story, she drops tantalizing clue after tantalizing clue as to the identity of this man, leaving a trail of breadcrumbs that Landis chases deep to the edge of some pitch-black places. Landis never goes so far as to guess the true identity of the lost love, and for good fucking reason. Once you get into the third act of this story, the theories that begin swimming in your head could be dangerous if said publicly but guessed wrong. I mean, the whole thing could be innocent. But what if it isn't?

And that's the magic of this piece. You may start it as a joke, but by the end, you find that there is a very real story here; the story of a woman whose life and art is defined by a single dalliance into forbidden love. And that story ain't a happy one, but it sure as hell feels like a true one. Maybe Jepsen is a snowjob, a character created by a brilliant writer playing the part she thinks everyone wants to see. But the evidence just doesn't support that. Landis really seems onto something here.

You see, what Landis is really tugging at is the specific uses of language in Jepsen's lyrics, not just the themes. My record scratch moment – the one that made me sit up straight in my chair and sling back the last of the whiskey in my glass – was during the break down of Emotions track 3, titled "I Really Like You." In it she sings: feel like I could fly with the boy on the moon/So honey hold my hand, you like making me wait for it/I feel like I could die walking up to the room, oh yeah. Landis immediately notes:

"Up to the room." It's an interesting way to say that. Not "your room," not "my room," but "the room."

She's meeting him in hotels. Not in apartments or houses.

And BAM! We're off to the races. This won't be the last time hotels are alluded to. Nor the oddly specific, and oft repeated, things that happen there. And as each piece of this puzzle gets laid down on the table, Carly Rae Jepsen the woman – not the rock star, not the writer – becomes more and more visible in the art. And Max can't stop trying to sharpen the image.

The Same Fucking Story

What begins as a lark ends up being a masterclass in drawing a character through small clues and repeated behaviors. Landis doesn't just pick apart Jepsen's work, he shows you little by little how to create a character out of scraps lying around, tying those bits together, and presenting them as a mostly intact entity. And by the time I was into EMOTIONS SIDE B, I found myself reeling at how dark the story the song "Stores" was telling – that of someone trying to recreate her heartbreak through one-night stands, then getting pissed off at the guys for not leaving before sunup like they were supposed to, meaning she has to be the one to leave, defeating the purpose of the whole endeavor.

And there I am, metaphorically sitting next to Max Landis as he looks at me and says "What did I fucking tell you, Cargill? It's all one story. It's. All. The same. Fucking. Story."

And it's actually a pretty great story.

A Scar No One Else Can See's only weakness stems from the nature of the work itself. It is, as Landis points out in the beginning, a living document; not a polished piece of writing. It has the occasional typo (which may disappear over time) and runs a little long in places that an editor would encourage Landis to tighten up. But with tightening and a little polish, it's easily a very publishable piece. But in a world of blogging and live-tuned news, these aren't uncommon or unforgivable flaws. It is, instead, the nature of what this is. You are going on a journey with Max Landis down a very strange little rabbit hole, and dear god, Alice, what an adventure you'll have.A Scar No One Else Can See is available as a single, downloadble document, or piecemeal as blogs through a delightfully fucked up, tongue-firmly-in-cheek little website. It can be enjoyed in chunks, or as I did it, in a several hours long single sitting that is a crazy little mindfuck all its own. One thing is certain, it's one hell of a bonkers, experimental piece of storytelling – a unique experience unlike anything attempted before. If you're the sort of person always interested in something off the beaten path, this is a piece well worth your time. It'll definitely be something you'll want to talk about, for better or worse, with someone after.C. Robert Cargill is a former film critic, an author, and a screenwriter of such films as SINISTER and MARVEL'S DOCTOR STRANGE. His latest book, SEA OF RUST, is available now from Harper Voyager.